By Kevin J. Jones

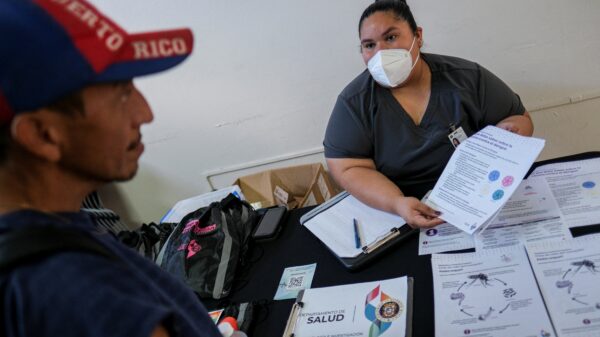

DENVER (OSV News) — The largest health care workers’ strike in U.S. history recently ended, and more labor disputes in the industry could be ahead. Though the strike — which included workers across several states — raises questions about negative effects on patient care, Catholic labor advocates and medical ethicists say all parties to the labor disputes make plans to avoid harm.

“None of these strikes happen without warning; they are announced ahead of time, allowing patients and facilities time to make alternative plans,” Joe McCartin, executive director of the Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor at Georgetown University, told OSV News.

To his knowledge, none of these strikes have been shown to lead to harming patients.

“Let’s keep in mind that the workers engaging in these actions have decided to devote their lives to providing care for others,” said McCartin, who describes himself as a labor historian whose work is influenced by Catholic social teaching.

“I don’t know of a strike in health care in which a central demand of the strikers was not for improvements in the patient care for the systems which they’ve dedicated their lives to working within,” he added. “In every case that I know of, workers are fighting to make their jobs more sustainable and their institutions better at providing care.”

Strikes at the health facilities of Kaiser Permanente took place from Oct. 4-7 in California, Colorado, Oregon and Washington state and the District of Columbia, and for one day, Oct. 4, in Virginia and the District of Columbia, CNN reported. Most labor action was concentrated in California. Workers who left their positions included nurses, pharmacists, optometrists, X-ray technicians, receptionists, medical assistants and sanitation workers.

The Coalition of Kaiser Permanente Unions collectively represents about 75,000 of the workers who went on strike and about half of the union workforce at Kaiser Permanente overall. The labor organizations involved in the strike followed federal rules that required them to give 10-day notice to authorities before striking. They sought higher pay and demanded vacant staff positions be filled, among other concerns.

The strike resulted in a proposed contract, which union members were voting to ratify in an election taking place from Oct. 18 to Nov. 3.

Ahead of the strike, Kaiser Permanente promised “robust plans” were in place to “ensure members continue to receive safe, high-quality care during the strike.” Hospitals and emergency departments remained open and the health care provider said contract staff would be brought in. According to The Washington Post, some laboratories had to close during the strike or had fewer staff, possibly delaying lab work. Some pharmacies also were closed or more limited in capacity. Some elective and nonemergency surgeries were rescheduled or postponed.

OSV News contacted Kaiser Permanente and the Coalition of Kaiser Permanente Unions for comment but did not receive an immediate response.

“I believe the unions put thought into this and took precautions so that patients in need of urgent care got it,” McCartin said. “Kaiser Permanente hospitals remained open during the three-day strike. Some pre-scheduled health visits might have been delayed, but not all delays are dangerous. By contrast, the union argued that failure to resolve the current chronic understaffing crisis, which was at the heart of its demands, is an ongoing and festering danger.”

Father Sinclair Oubre, spiritual moderator of the Catholic Labor Network and pastor of St. Francis of Assisi Catholic Church in Orange, Texas, told OSV News he knows many nurses who make “great family sacrifices to be there for their patients.” Many hospitals have moved to 12-hour work shifts, a prohibitive schedule for working parents. He said his parish high school director of religious education had started her nursing career on an eight-hour schedule but was forced to abandon her career after five years “because it was impossible to be a wife and mother with a 12-hour shift.”

“Nurses’ unions like National Nurses United and United Healthcare Workers West have been advocating for more nurses and the need for management to respond to the staffing shortage,” the priest said. “The unions were forced to push management to address an issue that endangered the nurses’ physical and mental health. If the nurses’ physical and mental health are compromised, the well-being of the patients are also threatened.”

From January to September 2023, there were six work stoppages in the health care and social assistance industry, involving 15,400 workers. Eight of the 23 major work stoppages that began in 2022 involved the same industry and involved 36,800 workers, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ publication The Economics Daily. The labor disputes could be a sign of more to come.

Nurses and nurse practitioners at Pittsburgh’s Allegheny General Hospital voted Oct. 17 to authorize a possible strike, citing a need for higher pay and more staff, WTAE News reported, but the strike was averted hours before it was to begin when a tentative agreement was reached Nov. 2, according to CBS Pittsburgh.

In New York, Rochester General Hospital and union member nurses have avoided a possible strike after reaching a tentative agreement to address complaints about wage and staffing shortfalls, the Rochester Democrat & Chronicle reported.

Catholic social teaching recognizes both the right to basic health care and the right to strike. The Catechism of the Catholic Church in paragraph 2211 discusses a right to medical care.

Pope Francis reiterated this right in Jan. 16 remarks to Italian health care specialists.

“A world that rejects the sick, that does not assist those who cannot afford care, is a cynical world with no future. Let us always remember this: health care is not a luxury, it is for everyone,” he said, according to Catholic News Service. In the same remarks the pope emphasized the need for “proper working conditions” and “an appropriate number of caregivers” to guarantee the right to health care for everyone.

Catholic teaching on the right to strike is compiled in various sources, including the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church, published in 2004 by the Pontifical Commission for Justice and Peace. The compendium says the rights of workers include the right to a just wage, the right to a safe working environment and the right to form labor organizations and to strike.

John F. Brehany, executive vice president and director of institutional relations at the National Catholic Bioethics Center, told OSV News that he previously worked at a Catholic hospital where the nurses had unionized and at times threatened to go on strike. Hospital administrators and other leaders have their own duty to ensure patient care, he said.

“Typically, administrators prepare for strikes by designing plans to address patients’ needs, including by hiring travel nurses on a temporary basis,” said Brehany. “Many hospitals typically prepare for strikes and can weather them in the short term, to avoid the worst impacts on patient care. I believe that labor strikes in health care are limited, but I don’t follow the trends closely. Everyone can suffer some harm if a strike is called — patients, potentially; the financial health of the hospital certainly; and even the strikers in some respects.”

“It may appear that a strike wrongly prioritizes employee interests,” Brehany added. “However, union members might say that they are striking only as a last resort, after bargaining has failed, because nurses are being significantly harmed (e.g., working conditions or compensation).” He also noted union members’ arguments that patients too are harmed because of improper staffing levels.

Brehany suggested the ethics of a union’s decision to strike, especially in health care settings, are comparable to the ethics of a nation’s decision whether to declare war or a person’s decision to defend himself with violence.

“All parties definitely have a right to do such things; each has important goods to protect. But these decisions should be made carefully, with good intent and with means ordered both by justice and by prudential considerations about consequences,” he said.

In Father Oubre’s view, management bears a responsibility for creating the conditions that result in a strike.

“No nurse wants to leave her or his patients,” he said. “So, the conditions must be very severe for her or him to take such extreme steps.”

McCartin said that much of the American health care system, including 40% of hospitals, operates on a for-profit basis.

“The real conflict it seems to me is one between profit and patient-centered care. That’s not a conflict the unions invented, it’s built into the system, but it’s one that they have to deal with,” he said.

“If not for organized health care workers, who would speak out and use their political influence to defend patients’ interests? Who will complain about short staffing and overworked care workers if not the workers themselves?” he asked. “If the workers take precautions of the sort the Kaiser Permanente workers took, the common good is served by these workers being organized, educating management, patients, and the public about their problems, and, when all other efforts at redress are exhausted, taking collective action to force some accountability on the system.”

Kevin J. Jones writes for OSV News from Denver.