(OSV News) — The Jan. 21 centenary of the death of Vladimir Ilich Lenin offers Catholics an opportunity to reflect on his historical legacy, and on how his role as founder of the Soviet Union still profoundly affects church communities.

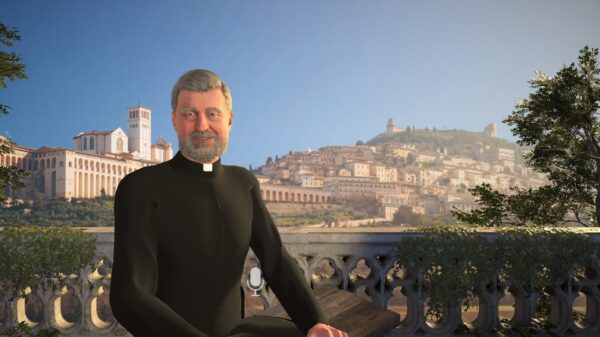

“Here in Russia, there won’t be any state commemorations, since President Vladimir Putin and others are divided over how to see Lenin — as the man who saved the Russian empire by giving it a new ideological direction, but who was also responsible for killing the Ttsar and other atrocities,” explained Jesuit Father Stephan Lipke, secretary-general of the Russian bishops’ conference.

“Even among Catholics, there are older people who sang songs about him in Soviet-era youth organizations and are reluctant to criticize him. Among clergy, however, I’ve never heard anyone defending Lenin — knowing the terrible things he did to people of faith,” the priest said.

Besides leading the 1917 revolution, Lenin is generally viewed as the architect of a 20th-century global struggle against “capitalism and imperialism,” drawing on the ideas of Karl Marx (1818-1883).

A red-granite mausoleum in Moscow’s central Red Square, housing his embalmed body, is still visited by Lenin enthusiasts, however, many Russian Christians nurse bitter inherited memories of his bloody rule.

“Whereas Marx believed religion would vanish by itself as life conditions improved, Lenin held the position that it had to be actively destroyed since it fueled subordination,” Father Lipke told OSV News.

“Although he wasn’t the only enemy of religion, he was the intellectual mastermind of the violent campaign against it. Although even his successor, Josef Stalin, later shifted temporarily to a milder policy, seeking to use religion rather than persecute it, this would never have been agreed by Lenin.”

Born in Simbirsk (later Ulyanovsk) in April 1870, Lenin was baptized as an infant and married with Orthodox rites to Nadezhda Krupskaya in 1898. He left religion firmly behind, however, concluding in 1909 it was too kind, paraphrasing Marx, to call it “the opium of the people.”

It was, in fact, “a kind of spiritual rotgut,” Lenin wrote, “by which the slaves of capital blacken their human figure and their aspirations for a more dignified human life.”

As for Christianity, Lenin concurred with Marx’s sidekick, Friedrich Engels (1820-1895), this was “deeply rooted in capitalist domination.”

Building communism meant eradicating the church’s presence in public affairs, as well as its influence on family life.

“Any religious idea, any idea of any god at all, any flirtation even with a god, is the most inexpressible foulness, particularly when tolerantly (and often even favorably) accepted by the democratic bourgeoisie,” Lenin told the writer Maxim Gorky in April 1913.

“A million physical sins, dirty tricks, acts of violence and infections are much more easily discovered by the crowd, and therefore are much less dangerous, than the nubile, spiritual idea of god, dressed up in the most attractive ideological costumes,” he continued.

By the outbreak of revolution, Lenin had served notice of his attitude to Russia’s predominant Orthodox clergy — “agents in cassocks” who had been employed by the tsar to “sweeten and embellish the lot of the oppressed with empty promises of a heavenly kingdom.”

While Orthodox dioceses and monasteries were stripped of estates and properties under a January 1918 decree on church-state separation, religious education was curbed and religious presences barred from families and workplaces, with 18 bishops and at least 3,000 priests, monks and nuns summarily slaughtered.

However, Russia’s Catholic clergy also were targeted, dwindling by half to around 400 by the early 1920s, in a campaign which culminated in a March 1923 Moscow show trial on spying charges of Archbishop Jan Cieplak and his vicar general, Msgr. Konstantin Budkiewicz (both of Polish nationality), the latter executed in Moscow Lubyanka prison five days after his conviction. Archbishop Cieplak was only spared because of international fury that followed his conviction but which did not manage to save Msgr. Budkiewicz.

Lenin’s brutal heritage included introducing the world’s first legal abortion program and numerous other moves against Christian values.

Although Stalin, a one-time Orthodox seminarian, had a more complex personal view of religion, he continued the eradication of churches after taking power in 1924.

Communism’s peacetime death toll in the Soviet Union would later be put by Russian researchers at 21 million, with some 110,000 Orthodox priests, monks and nuns killed in the first two decades of Soviet rule, and 45,000 Orthodox churches left in ruins.

As for Russia’s Catholics, 422 priests were executed, murdered or tortured to death during the same period, along with 962 monks, nuns and laypeople, while all but two of the church’s 1,240 places of worship in Russia were closed or turned into shops, warehouses, farm buildings and public toilets.

While claiming religious freedom in its constitution, the Soviet regime never abandoned Lenin’s aim of eradicating religious belief, and continually targeted “superstition and fanaticism” as a foil to progressive and rational Soviet values.

Even today, with a Moscow-based archdiocese and three suffragan dioceses in Saratov, Irkutsk and Novosibirsk, Russia’s 700,000 Catholics still seek the return of seized churches and encounter problems exercising rights at local level, with some older church members still harboring recollections of prison and labor camp sentences.

A Catholic Church commission, established in 2002, is seeking the beatification of 16 communist-era martyrs, including two bishops: the Polish-born Antoni Malecki of Leningrad, who died after being deported to Poland in 1934, and the German Jesuit Edward Profittlich, who died in 1941 while awaiting execution in Kirov prison.

A Russian Catholic university professor, who asked not to be named, told OSV News Lenin’s popular standing in Russia declined in the 1990s, as archival evidence of his brutality came to light.

He fears, however, that his legacy is now being revived — not least through Moscow’s drive to rebuild its empire by reoccupying Ukraine and the growing militarization of Russian society, which has included the revival of Soviet-era youth movements and the return of weapons training to schools.

In such an atmosphere, Russia’s minority Catholics could find themselves targeted, as they were Jan. 14, when groups gathered outside Moscow’s Catholic Immaculate Conception Cathedral and St. Louis Church to protest the Catholic presence.

“Lenin’s anti-religious views played a brutal role in the Catholic church’s early 20th century suppression, when its members were branded Vatican agents,” said the lay Catholic, a former member of the Pontifical Council for the Laity and adviser to Vatican Radio.

“If Russia’s present government wishes to seek out an enemy, Catholics would make an easy choice — so this centenary should be a warning. Although no one praises Lenin directly, the Leninist mentality is still deeply rooted in state rhetoric here, especially in the call for national unity and the primacy of the collective over the individual.”

Jonathan Luxmoore writes for OSV News from Oxford, England.