(OSV News) — Dr. Paul Carson remembers when COVID-19 first commanded his attention: In late February 2020, the virus swept through a Washington state nursing home, ultimately killing dozens of its residents. Carson — a doctor and infectious disease specialist — was the medical director of a North Dakota nursing home. He put precautions in place, expecting his expertise to make the nursing home the safest in his state. Instead, it was the first to be hit.

“Within a matter of a few weeks, the first wave killed about a fourth of all our residents. It was devastating,” said Carson, a Catholic who teaches in the department of public health at North Dakota State University in Fargo.

As of late May 2023, COVID-19 has taken more than 6.9 million lives around the globe, including more than 1.1 million in the United States.

However, the numbers of COVID cases, hospitalizations and related deaths have waned, with deaths the lowest they have been since the pandemic began, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. After declaring COVID-19 a pandemic in March 2020, the World Health Organization announced an end to its emergency phase May 5, calling the virus “now an established and ongoing health issue which no longer constitutes a public health emergency of international concern.”

Carson said the decision is appropriate. “It’s a lot more manageable now through vaccinations and medications available to us,” he said of COVID.

As the world marks this milestone, Carson and other Catholics say there are important takeaways for the church as it considers its ministry now and prepares for future pandemics, given the realities of international travel and trade.

COVID-19 — short for “Coronavirus Disease 2019” — was first identified in December 2019 in Wuhan, China, and the virus was likely responsible for deaths in the United States a month later. In March 2020, as COVID’s reach became apparent, states began to implement shutdowns in hopes of stopping, or at least slowing, its rapid spread. Schools and offices closed, and education and work went remote. “Essential workers” adapted their jobs. In the middle of Lent, U.S. bishops began to call on their dioceses’ parishes to close churches and suspend public Masses, dispensing Catholics from their obligation to attend Sunday Mass. Pastors and parish employees pivoted to livestreamed Masses and social media to connect with congregations.

After initial stay-at-home-style recommendations were lifted, Masses moved outdoors and to parking lots, and confessions were heard through car windows. Priests volunteered to anoint the dying, and learned from medical experts how to safely don and doff personal protective equipment. Liturgical experts sought creative ways to validly offer the sacrament under the ever-evolving circumstances.

Speaking in front of an empty St. Peter’s Square March 27, Pope Francis offered a special Urbi et Orbi (“To the City and to the World”) blessing, usually reserved for Christmas and Easter. He encouraged “embracing the Lord in order to embrace hope: that is the strength of faith, which frees us from fear and gives us hope.” The message was delivered amid a steady rain, underscoring the solemnity of what, for many Catholics, was a poignant moment that made for a lasting memory.

In May 2020, states began reopening businesses, restaurants and public venues at dramatically reduced capacity, and dioceses followed suit, recommending Masses be offered with limited attendance, masking and social-distancing requirements, no singing and Communion only under one form.

In the months that followed, public spaces restrictions eased — but, for churches and other religious spaces, not always without a fight.

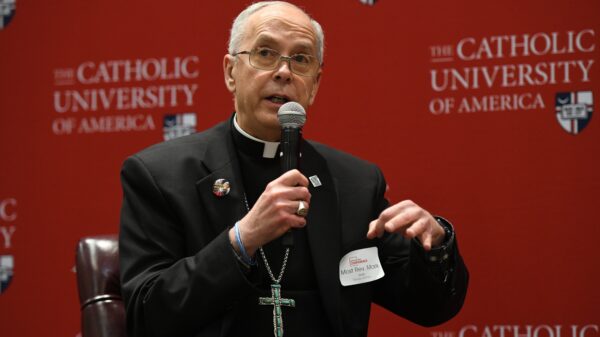

In many cities and states, businesses and bars faced looser restrictions than houses of worship. In Nevada, for example, casinos were allowed to reopen at 50% capacity, but churches were not. Similar scenarios played out in California, Minnesota and elsewhere, including Rhode Island, where Dr. Timothy Flanigan — an infectious disease doctor who teaches at The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University and practices at affiliated hospitals, as well as a Catholic deacon in the Diocese of Providence — works. He served as an expert for many churches making their case to civil authorities for treatment on par with other public places.

“Many authorities did not value the sacraments and prayer and worship, so therefore they actively prevented it, even though they allowed other gatherings,” he told OSV News May 19.

Flanigan worked in the hospital during the height of COVID and saw firsthand the suffering of the sick and the heroism of health care workers, particularly the bedside nurses.

“I was both very proud of many of my colleagues, both in medicine and in the church, who became involved despite the fear that existed,” said Flanigan, who contributed to the guidance offered by the Thomistic Institute in Washington for providing the sacraments during the pandemic in accord with WHO standards. “That is in the tradition of both people of Catholic faith and the institution of medical care providers.”

Carson, who advised both state officials and the Fargo Diocese in its COVID response, said he was pleased overall with how the institutional church responded to the pandemic. “I felt they truly strived to strike the balance between following the science as it evolved, ensuring the safety and solidarity with one another (a public health goal), while still ministering to the spiritual needs of the faithful,” he said.

He also appreciated the guidance the then-Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) offered to help Catholics navigate the moral and ethical questions surrounding vaccination. Cell lines derived from aborted fetal cells were used in the research and development of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, and in the production of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, prompting Catholics to question whether to take them.

The CDF (since renamed the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith) issued a statement in December 2020 saying that in absence of an ethically created COVID vaccine, “it is morally acceptable to receive Covid-19 vaccines that have used cell lines from aborted fetuses in their research and production process,” because “the moral duty to avoid such passive material cooperation (with evil) is not obligatory if there is a grave danger, such as the otherwise uncontainable spread of a serious pathological agent.”

The CDF also said that vaccination should, however, be voluntary, and that people who refuse the vaccines for reasons of conscience must also take steps to avoid transmitting it.

Despite the CDF statement, the morality surrounding vaccination persisted among Catholics as deeply controversial. Some Catholics sought letters from their bishops supporting their religious exemption from vaccination.

“The (church’s) formal statements on vaccines were thoughtful and balanced our responsibilities to care for ourselves and one another, while still respecting an individual’s conscience,” Carson said. “One thing that I think could have been better would be to provide greater clarity on what constitutes true matters of conscience for a Catholic weighing whether to take a vaccine or follow a work-required mandate.”

As church leaders sought to provide the sacraments and continue ministry during the pandemic, the Federation of Diocesan Liturgical Commissions (FDLC) in Washington served as a clearing house for diocesan and parish liturgists advising their bishops and pastors.

Rita Thiron, FDLC executive director, remembers the flurry of conversations in spring 2020, especially as Holy Week approached. The organization shared daily information from the Vatican, canon lawyers, dioceses and church-affiliated institutions, and as Catholics returned to Masses, it continued to help church leaders navigate evolving best practices that considered both public health and spiritual needs.

While dioceses around the country seemed to “shut down” all at the same time, reopening happened at different paces, Thiron said. In some places, it was nearly business as usual in the summer of 2020, although U.S. dioceses did not begin lifting the dispensation from Sunday Mass obligations until 2021. By contrast, Catholics in the Archdiocese of Chicago were not obligated to return to Mass until November 2022, although archdiocesan leaders had encouraged Catholics to return to Masses months before.

Today, parishes are likely to be back to pre-pandemic practices, including extending the sign of peace and offering both the body and blood of Christ at Communion, but it has taken three years to get there, Thiron said. For parishes not yet distributing the Eucharist under both forms, “I hope that that is restored to the fullest sign of the sacrament very, very, very soon.”

“I hope the thing we learned most is that we all hungered for the Eucharist,” Thiron said. “I know how meaningful it was to hold that Host in my hands again after a long time, and recently to receive the Precious Blood after a very, very long time.”

In June 2021, the Archdiocese of Los Angeles, which was hit particularly hard by the virus, became one of the first U.S. dioceses to reinstate the Sunday Mass obligation. Advising his fellow priests through that transition was Father Juan Ochoa, who directs the archdiocese’s Office for Divine Worship. Also the pastor of Christ the King Parish in Hollywood, Father Ochoa had balanced his archdiocesan leadership role with his parish responsibilities since the beginning of the pandemic.

Keeping connections with parishioners was key. He placed a copy of his parish roster by the tabernacle, and he, parish staff and volunteers reached out to members by phone, email and letters to see what people needed. They hosted a food drive and made pharmacy runs. They livestreamed Mass and organized weekly prayer services to bring people together — especially those who, even before the pandemic, were lonely and isolated, whose only communal meal each week had been donuts after Mass.

“What do you do as a mom when your children are sick? You’re there with them. You are providing medicine. You are being present to them,” Father Ochoa said. “We say that the church is a mother, and we need to be a mother for our parishioners.”

He also encouraged his flock to look to the saints. In the history of the church, plagues gave rise to great saints, including St. Cyprian, St. Roch, St. Sebastian, St. Charles Borromeo, and much more recently, Knights of Columbus Founder Blessed Michael McGivney, who died at the height of his ministry during a flu outbreak in 1890, and St. Damien of Malokai, who lived and eventually died among those with leprosy in Hawaii.

In light of these models, Father Ochoa thinks Catholics generally scored “very low” in their Christian response to COVID-19. Instead of looking to faith, many Catholics turned to the media “to dictate how to be a church,” he said.

“It was a moment that everyone was fearful. Everyone was dealing with the unknown. That was an opportunity for us to proclaim Christ as our hope,” he said.

Practically, that could have included Catholics embracing vaccination as a witness to love of neighbor, said Carson, the doctor in Fargo. He was disappointed in the “my body, my choice” attitude and rhetoric, commonly used to defend abortion, used instead to justify non-vaccination, including by pro-life Catholics.

“Of course, we as Christians, it isn’t our body, it’s God’s body. We look at what we do and how we act as affecting others, and we need to be the leaders in self-sacrificing for others,” he said.

Father Ochoa said Christians “don’t allow fear to dictate how we live our life.” It’s like a dance, he said, where faith and fear are partners. “The one that has to be leading the dance … has to be faith, not fear.”

Maria Wiering is senior writer for OSV News.