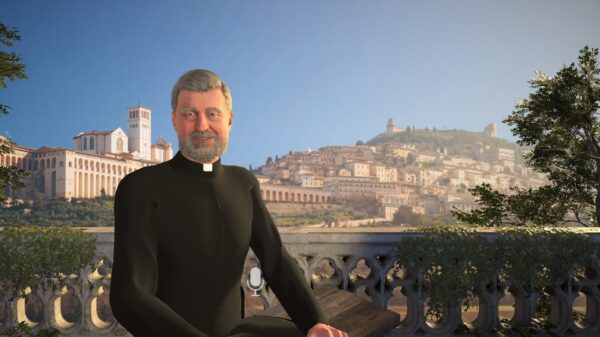

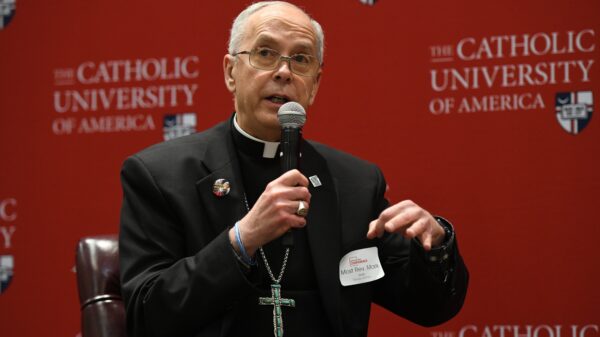

On June 29, 2018, Pope Francis announced the appointment of Most Rev. Peter Andrew Comensoli as the ninth archbishop of Melbourne, Australia, the largest archdiocese in Oceania. Prior to that, Archbishop Comensoli had served as bishop of the Diocese of Broken Bay (2014-2018) outside of Sydney, and as auxiliary bishop of the Archdiocese of Sydney. He holds a licentiate of sacred theology in moral theology from The Pontifical Alphonsian Academy in Rome and a doctorate of philosophy in theological ethics from the University of Edinburgh. Charlie Camosy gets to know the archbishop for OSV News and we’ll chat with him at a later date regarding his 2018 book “In God’s Image: Recognizing the Profoundly Impaired as Persons” (Cascade Books).

Charlie Camosy: Can you tell us a bit about the story of how you became a priest? How did you discern that call?

Archbishop Comensoli: I came from a family — mum, dad and three brothers — where faith was just a part of life, though we were not overly religious. I had an auntie who was a religious sister and a cousin who was a priest, so a religious vocation was not entirely alien to me. The thought of priesthood first came to me in the final years of high school, but I promptly put it aside, as a more ordinary path into adulthood loomed — go to university, pursue a career, get married. At the age of 16, the prospect of finding a girlfriend was more appealing than pursuing priesthood.

I got a job in a bank and commenced part-time studies at university. I also became involved in a young adults group called “Antioch.” But the thought of a priestly vocation never quite left me, niggling away quietly as I got on with life. For four years this niggling persisted and got quite annoying. I wasn’t really attracted to the prospect, yet it wouldn’t go away. Finally, I thought I needed to “get it out of my system.” I asked my cousin to contact the local bishop and before I knew it, I had entered the seminary. And that was it.

During seminary I became gradually more convinced that a priestly life was indeed where the Lord wanted me, and gradually more comfortable with the prospect. So, having started out wanting to get the idea of priesthood “out of my system,” Jesus had won me over, and I haven’t looked back (very much) since.

Camosy: As a new seminary professor, I’ve become aware of the pressures on priests which pull them away from what originally drew them to the priesthood. I imagine that’s even more the case for bishops. How do you manage in this regard?

Archbishop Comensoli: I am quite mindful of a major vocational challenge anyone of faith faces — it is the challenge of moving from the image of the vocation (ordained ministry, religious life, marriage) to the reality. It is a move that we all need to make. Sadly, a number of recently ordained never quite make this shift. They struggle to see themselves in a priesthood that is not the image of what had been fostered in the seminary.

Every vocation needs to find the reality of its life and meaning, for Jesus does not call us to anything else. There is no “perfect” priesthood (or religious (life), or marriage) that we will attain. Learning to accept the beauty of the ordinary, along with the contentment of the struggles, is part of coming to live well our vocational journey.

I can hardly say a bishop is “drawn to the episcopy”! The priest who wants to be a bishop, or who thinks he is destined to be a bishop, is precisely the priest you do not want as a bishop. But the same sort of factors are at play: the images of the episcopal life — of authority, or leadership or honor — are all there to trip you up. Go to the reality (in the case of bishops, that means the apostolic reality of “being sent”), and there you will find a way ahead, in Christ.

Camosy: What might readers be surprised to learn that you actually like about being a bishop?

Archbishop Comensoli: I’ve actually gotten quite used to carrying and standing with the crosier. I like leaning into my crosier when the Gospel is being read, for example. Somehow, I feel something’s missing at those times when I’m not holding it — I don’t quite know what to do with my hands!

Camosy: What does Archbishop Comensoli do for fun? Favorite movies, TV shows, music? How can we get more insight into this part of who you are?

Archbishop Comensoli: I have a passion for doing jigsaws. I’m currently working on a 5,000-piece jigsaw of Bruegel’s “Tower of Babel,” which I potter away at when I get an hour or so of spare time. It’ll take a year to get it completed. I’ve become very fussy about what jigsaw image will interest me, but it’s the process that matters — getting into the groove, losing myself in the task, spotting the patterns. Doing a jigsaw is weirdly therapeutic for me. Once it is completed, I break it up almost immediately.

Camosy: Particularly in an era of near constant “noise,” often coming to us through our smartphones, do you have any advice for those who want to better connect with the younger part of ourselves who may have heard the voice of God more clearly? What best (spiritual) practices would you suggest?

Archbishop Comensoli: Gee, how important is silence these days! I’ve actually advised people in the confessional to try and have no devices going while driving every now and then (phone, radio, etc). Try it — no background music, or podcast or anything; just the sound of the cars around you. It can be quite liberating, or it could be quite scary.

I don’t claim to be some great pray-er, so I do not have any great spiritual insight to offer. But finding windows of prayer and pausing is really helpful. If someone asks you for prayer, say a Hail Mary with them, right there and then. Find five minutes of silence each day. Read a bit of Scripture slowly — one or two verses is more than enough — and recall it through the day, if you can. Just say hello to Jesus. And try not to boast about how much prayer time you are doing — remember, it is not those who say, “Lord, Lord” who get to heaven!

Charlie Camosy is Professor of Medical Humanities at the Creighton School of Medicine and Moral Theology Fellow at St. Joseph Seminary in New York.