WASHINGTON (OSV News) — More than a year after floods submerged one-third of Pakistan, “women in particular are (still) being impacted,” said the head of programming for Catholic Relief Services in the country.

Although some men are involved in reconstruction of damaged homes, canals and roads, many women — who worked as tenant farmers or did embroidery to contribute to the household income — have been unable to resume work. Women-led households are especially affected.

Some families in the province of Baluchistan are “still living in scorching sun, with no kitchen or bathroom spaces,” said Gul Wali Khan, Pakistani program manager for CRS, the U.S. bishops’ international relief and development agency. He said daytime temperatures often reach 122 degrees Fahrenheit.

One farmer told CRS when there are no latrines, women need to go far away for privacy, and some were waiting until after dark — at which point there were concerns about snake bites and sexual exploitation.

More than 33 million people were affected by the 2022 floods, caused by a severe heatwave that melted glaciers, followed by heavier than usual monsoon rains. Khan said 8 million people left everything to flee to safer places — which in some cases meant the high embankments of canals or the sides of elevated roads. Some spent nights in the rain with only wet clothing on their heads to protect them. More than 1,700 people died and more than 12,000 were injured.

The government estimates the flood caused $14 billion in damages, but that does not include the ongoing costs to families, Khan said. And this year’s monsoons and flooding had left more than 200 people dead by the end of July.

After the 2022 monsoons, “water was standing for weeks and months” on some of the 4.4 million acres of farmland affected, Khan said. It destroyed the first season of crops — rice and sugar cane — and damaged grains stored from previous crops. Because of the standing water, farmers could not plant wheat for the second growing season, and when the ground in some areas was ready for planting, farmers “could not afford fertilizer and adequate seed.”

The farm “landlords” purchased the seed and fertilizer for the farmers, who cannot purchase them on credit because they have nothing as a guarantee. After the women work in the fields and harvest the crops, the landlords deduct the cost of supplies, then split the remaining profits with the farmers. But production decreased after the flooding, and interest was high, so now more supplies must be purchased on credit from the shopkeepers. Khan described the situation “sort of like a type of bonded labor … a vicious cycle of debt.”

“I was talking personally with the women the other day and some of them were crying,” saying they were not sure if they would ever get out of debt, Khan told OSV News in early September.

Women who contributed to the household income through embroidery also have faced struggles, Khan said. “Because they lost everything” they could not get materials, and even if they could, there was no one in the market to buy their embroidery, or there was no dry place for them to work.

“I have seen women … begging for a space, like a house, so they could have a proper space so they could sit and do some embroidery work,” Khan said.

Because of the economic stresses on the households and because women are not contributing, some have been exposed to gender-based violence, Khan said. Women will not tell CRS staffers directly about the violence, he said, “but when you are in the community, they talk about it.”

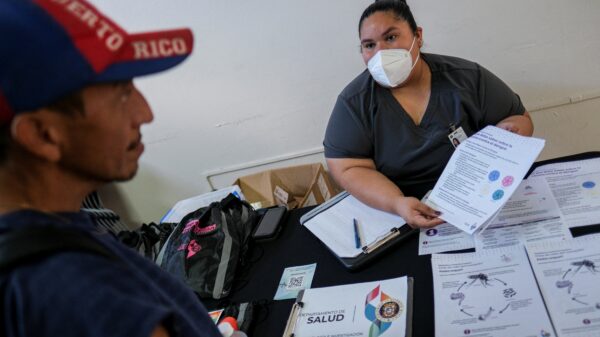

CRS and its Pakistani partners are working with the government of Sindh province, the country’s second-most populous province and one of the worst affected by the rains; it’s “like a drain province to the (Arabian) sea,” Khan said. The agencies have sponsored sanitation and clean-water projects, cash disbursements as well as micro-economic projects to help women embroider garments or stitch “rillis,” a traditional floor covering.

But CRS also is working to fund the construction of houses that can withstand the increasing challenges of climate emergencies, Khan said.

The Sindh government has World Bank funding for about 350,000 houses — about 20% of the number that need to be rebuilt. Following guidelines set out by the provincial government, CRS is helping with 700 additional houses.

“It’s an owner-driver approach” in which the owners get the funds in installments, following steps to completion, Khan said. In addition, CRS and its partners help train the local masons to ensure the minimum standards for resilient housing and help identify proper material for the local weather and environment.

CRS also has been approached by the province to help establish a coordination platform to help reach out to international donors, nongovernmental organizations and the U.N. to help get resources to reconstruct more of the housing. The program is modeled on a platform CRS began leading in Nepal after the magnitude 7.8 earthquake there in 2015.

But Khan expressed frustration that, unless something is done about climate financing, the situation will repeat itself. He notes that Pakistan ranks among the top 10 countries most affected by climate change, but it contributes less than 1% to global gas emissions.

He said changing weather patterns that produce tropical storms affect rainfall patterns in rural communities. In the past, he added, heat waves occurred in pockets of Pakistan, but the number of days has increased.

He said the world must be educated to see climate emergencies as people emergencies, because “the miseries of these people are still increasing.”

Barb Fraze writes for OSV News from Virginia.