Much of the western world celebrates work and workers on May 1, either as the secular International Workers’ Day or the Catholic Feast of St. Joseph the Worker. In the U.S., as of 1894, the first Monday of September has been celebrated as Labor Day. The busyness of the three-day weekend marking the end of summer leaves little time to consider the actual purpose of the holiday. Instead, it’s a weekend of back-to-school shopping or a final visit to the beach. A remedy to these distractions, and an enriching way to deepen our understanding of the Catholic teaching about work and workers, is to revisit Elia Kazan’s magisterial film, “On the Waterfront.”

Set in the late 1940s, the film is a fictionalized account of actual corruption in the longshoreman’s union that controlled labor on the loading docks of New York City, as described in the “New York Sun” by Pulitzer Prize winning reporter, Malcolm Johnson. Moving the setting to Hoboken New Jersey, and with a stellar cast, the film is a deep dive into Catholic social doctrine, including the nature and purpose of work, the solidarity of all people, the temptations of power, and the resiliency of faith.

The Corruption of Work

The longshoremen of Hoboken engage in a daily struggle for a place in line at the docks, hoping for a means to scrape out another day’s meager wages. Their union, the purpose of which is to protect and unite the laborers, instead parcels out work to the favorites of the boss, Johnny Friendly (Lee J. Cobb), according to how relatively compliant they are with his corruption. The key to getting work each day is not the worker’s skill and dedication to the job, but rather his commitment to an ethic of “deaf-and-dumb.” The first places in line for the easiest jobs are for those who turn a blind eye to the bribery and skimming that enrich Friendly while impoverishing the rank-and-file. The boss’s greed leaves little for the workers, but a little is better than nothing. The cruel irony is that the union serves as the source of the workers’ misery instead of their relief. Rather than a means to the proper end of work — the leisure to pursue higher goods — work is a dog-eat-dog drudgery, doled out at the whim of the corrupt union boss and his complicit lackeys.

This arrangement is disturbed when one of the workers, Joey Doyle, decides to testify to a committee investigating corruption at the docks. Johnny Friendly’s right-hand-man, Charley Malloy (Rod Steiger) dupes his brother, washed-up boxer Terry Malloy (Marlon Brando), to lure Doyle into the hands of Friendly’s henchmen, who murder Doyle. The murder serves not only to silence a potential witness against Friendly, but to further intimidate the other dockworkers.

The Labor Priest

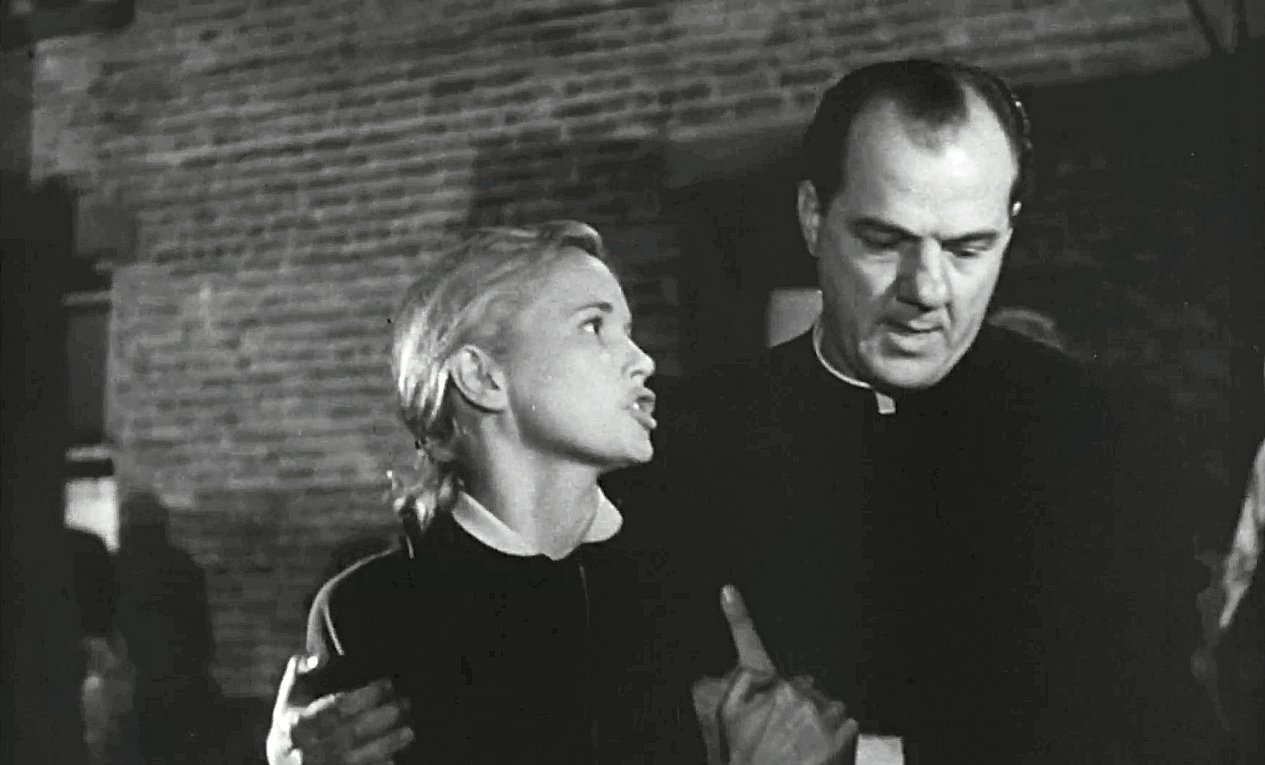

Doyle’s murder, and the corruption it protects, come to the attention of the parish priest, Father Barry (Karl Malden). Challenged by Joey Doyle’s sister Edie (Eva Marie Saint) to become involved, Father Barry convinces another worker, Kayo Dugan, to testify in confidence to the committee. When word of Dugan’s testimony inevitably leaks, he, too, is murdered by Friendly’s button men. Fueled by righteous anger at the injustice, Father Barry begins to work on the conscience of Terry Malloy to do the right thing and testify against Friendly, regardless of the potential risk.

Father Barry is the archetype of the frontline labor priest, stepping down from ambo and altar to tend his flock where it toils. He arranges a clandestine summit in the church, meets individually with Terry over a beer at the corner bar and, ultimately, goes to the docks to “smell the sheep,” as Pope Francis has taught us to say.

My Brother’s Keeper

But while Father Barry is counseling Terry into authentic solidarity with his union brothers against Friendly, his biological brother, Charley, tries to convince Terry to keep the “deaf-and-dumb” code. This leads to the most famous lines of dialogue in the film, in which Terry accuses Charley of his failure to be his brother’s keeper. Bribed to take a dive in a boxing match fixed by Charley, Terry lost his chance at a championship bout. “You was my brother, Charley, you shoulda looked out for me a little bit,” says Terry. “You shoulda taken care of me just a little bit, so I wouldn’t have to take them dives for the short-end money.”

If you have seen the film, you know what happens after this famous scene. If you have not, I do not want to spoil the wonderfully moving ending. Themes of brotherhood, the dignity of work, and the solidarity of the union all play a crucial role in the stunning resolution of the film. Watching (or rewatching) “On the Waterfront” would be a salutary way to redeem a bit of the time of Labor Day weekend.

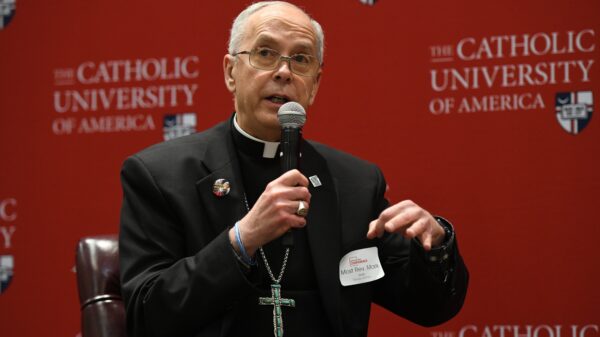

Kenneth Craycraft is an associate professor of moral theology at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary and School of Theology in Cincinnati.