By Olivia Poust

(OSV News) — Deep in the Caucasus — at the crossroads of Asia and Europe — lies the contested region of Nagorno-Karabakh, an Armenian-populated enclave surrounded by Azerbaijan, which launched a military assault in September 2020 to regain control of the land.

Once a lush, bucolic area, populated for centuries by Christian Armenians and later Shiite Muslims, it has become an elusive point of contention between the Armenian and Azerbaijani peoples since the decline and fall of the Soviet Union.

The enclave’s isolation had been mitigated by the Lachin corridor, through which runs a road that has connected the region to Armenia proper. Since December 2022, however, Azerbaijani activists blockaded the route, in effect severing Nagorno-Karabakh and its ethnic Armenian residents from the outside world, with the exception of the International Committee of the Red Cross and Russian peacekeepers, who the combatants agreed could provide humanitarian support to the region.

This blockade tightened June 15 when all traffic on the lifeline, including the ICRC and Russian peacekeepers, was blocked. The ICRC “carried out transportation of medical patients and a very small amount of medicine … several times,” after this ban, but on July 11, Azerbaijan accused the ICRC of “smuggling” through the corridor and restricted its movement entirely, according to Siranush Sargsyan, a reporter based in Stepanakert, Nagorno-Karabakh. The shortage of supplies for the region’s population of 120,000 is acute.

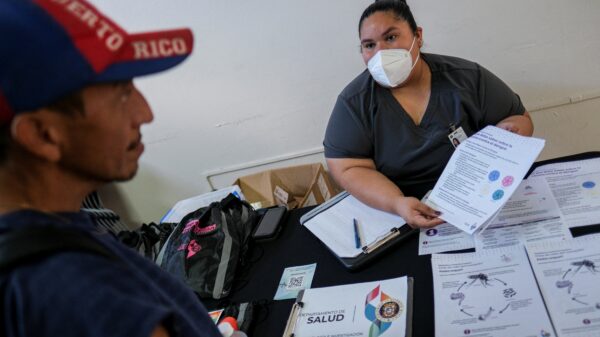

Those blocking access are preventing approximately 400 tons of humanitarian aid from Armenia to enter Nagorno-Karabakh, reported Lusine Stepanyan, project manager for Caritas Armenia. The agency is a Catholic Near East Welfare Association partner that has supported refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh with food, medical supplies, education, psychosocial support and funds for housing.

CNEWA has provided aid for those displaced and cared for by Caritas and the Armenian Catholic Ordinariate.

Sargsyan noted in an interview with CNEWA that in her city of 60,000 people, “it’s like hunting for food, for basic things.”

“Usually, you go back (home) empty-handed,” she said.

While supermarkets are practically empty, food products such as eggs and bread can be purchased from smaller shops and bakeries, but there is no guarantee that standing in the long lines will prove fruitful, she explained. For eggs, which are available to purchase every other day, people begin lining up around 5 a.m., but they are not distributed until 3 p.m., said Sargsyan. Even then, it is common for them to run out.

“It’s already, I think, months that I can’t find eggs, because I’m not ready to stand in a line and because … it’s better that mothers buy for their kids,” she said.

Sargsyan said this is the worst the humanitarian situation has been since the blockade began. She noted that winter posed its own set of challenges due to the cold, but the current shortage of food, medication and fuel has created a dire situation. Although supplies before the blockade tightened in June were still limited, and prices were not ideal, “at least it was possible” to find these items, she said.

The Artsakh Information Center reports “the electricity supply has been completely disrupted for 200 days,” as well as the complete or partial interruption of the gas supply for 162 days. Ms. Sargsyan says this shortage has contributed to a spike in unemployment for those whose jobs are reliant on this supply, like taxi drivers; the Information Center estimates that 14,600 people have lost their jobs or source of income since the blockade began in December and the economy has “suffered a loss of around $435 million U.S. dollars.”

Recent television interviews with the leaders of Azerbaijan and Armenia highlight separate discussions on the path to peace, and what that would require for their respective nations. For Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev, this includes Armenia relinquishing “all aspirations to contest our territorial integrity.” Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan said, “There must be peace,” and that it is “important for the international community to be aware of important nuances,” Reuters reported.

While their propositions for peace leave much uncertainty, the situation in Nagorno-Karabakh remains a humanitarian crisis for those on the ground.

“We can say there always is a light at the end of the tunnel, but we don’t see. It’s like endless, this tunnel,” said Sargsyan. “And every day it’s getting darker and darker.”

Olivia Poust is communications assistant for Catholic Near East Welfare Association and writes for ONE, the publication of CNEWA.