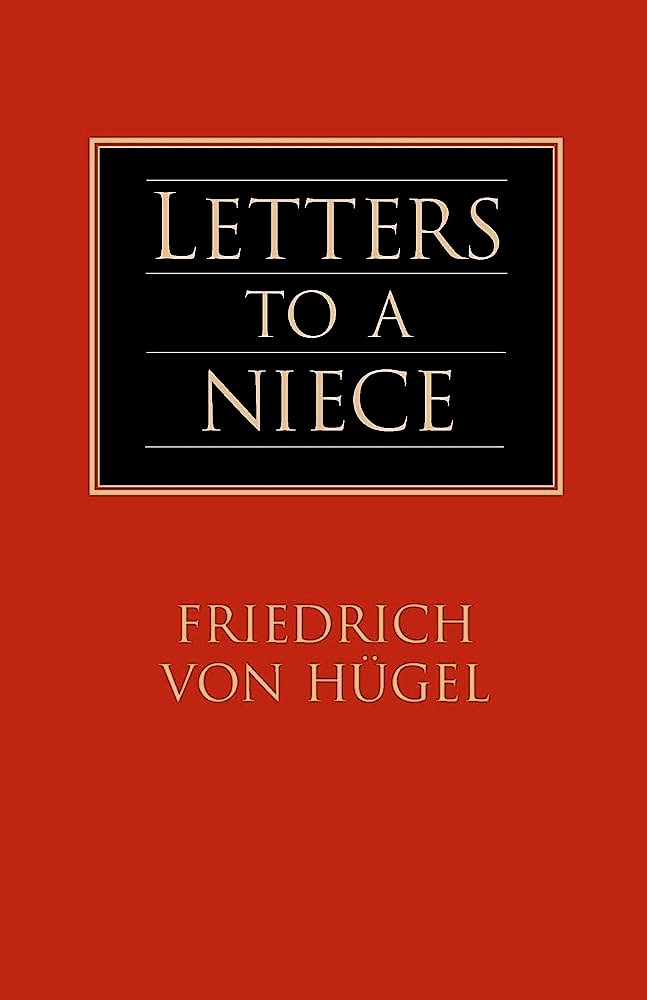

Friedrich von Hügel’s niece was a bit of a snob, and being a snob was bad for her, especially the kind of snob she was. The Austrian-English Catholic theologian was a highly intelligent, highly learned and cultured man, a scholar admired across Europe. If anyone had a right to be an intellectual-cultural-spiritual snob, he did.

He wasn’t, but his niece, Gwendolyn, was. “Only the best attractive to you,” he noted in one of his letters to her, collected in “Letters to a Niece.” (The letters were given as intellectual and spiritual direction, and were written from 1918 till he died in 1925. It’s a great book. Gwendolyn was hugely blessed.)

Her problem wasn’t just plain old snobbery, though. It was a feeling Hügel called “fastidiousness,” and it’s one I suspect many of us have. (I speak of something I know much too well.) We demand things be done to a high standard, without any mess or imperfection — especially without any mess or imperfection. We want it just so.

Is that, we tell ourselves, too much to ask for in the important things? Can anyone blame us for keeping our distance from the messy and imperfect?

A particular faith

Gwendolyn was an Anglican and a serious Christian. Before warning her about her problem, Hügel tells her that she has “the great grace to love and to worship Christ our Lord.” If I read her uncle’s direction right, she believed in the Christ who had a body but wasn’t comfortable with the Body of Christ. She didn’t like to go into churches with people in them.

Nor into churches where things were not done well. She did not go to church services in the country, for example, apparently because the services didn’t meet her standards, and she didn’t like the homilies. They weren’t clever enough for her. She doesn’t seem to have liked them much better in the city, either, and for the same reasons. She did accept services at churches that did things just so, which tended to be those in the more affluent parts of London.

Fastidious Gwendolyn

She was, in a word, fastidious. Fastidiousness is “a very hideous thing,” Hügel tells her. He comes as close as he ever does in his letters to laying down the law. Someone “dominated by such fastidiousness, is as yet only hovering round the precincts of Christianity.” That person “has not entered its sanctuary, where heroism is always homely.”

“The touching, entrancing beauty of Christianity, my Niece, depends upon a subtle something which all this fastidiousness ignores,” he writes to her. “Its greatness, its special genius, consists, as much as in anything else, in that it is without this fastidiousness.”

He reminds her that Jesus the Light of the World was “the menial servant at the feet of those foolish little fishermen and tax-gatherers.” He points to St. Francis, who so loved God that he took up a life as anti-fastidious as it’s possible to be. “The full, truly free, beauty of Christ alone completely liberates us from this miserable bondage.”

Finding the good in the imperfect

Of course, the fastidious Catholic’s standard is more a matter of personal taste and less objective than we think. We tend to confuse “the best” with “what I like.”

It’s just practical! The best helps you more than the less-than-best. You learn more from a good homily than a bad homily, are better formed by a well-celebrated liturgy than a badly celebrated one, find more meaning in a beautiful statue than in a kitschy one. It’s not your fault that other people can’t tell the difference.

As with many things in our lives: yes and no. The homily that would make a seminary professor weep may carry more wisdom than the most elegant one you will ever hear. People may sing “On Eagles’ Wings” with sincere and deep piety, and you will gain more by joining in than by pining for something better. People may come to that sentimental Madonna with a deep love for Mary that they wouldn’t feel with a classically beautiful one. Not the best in one sense, but the very best in another.

Hügel doesn’t expect his niece to see the problem very quickly. Fastidiousness runs deep. It’s a cast or habit of mind (as I know). He tells her to go to church when she’s in the city and especially to holy Communion. He asks her to “ruminate” on what he’s told her and beware anything that seems to confirm her fastidiousness. And “if and when you come fairly to see it to be a poor, a very poor, thing,” ask God “gradually to cure you of it.”

Here’s the worst part. The fastidious Catholic rejects mess and imperfection. But the messiest and least perfect thing that a Catholic will meet is other Catholics. Fastidiousness tempts us not just to look down upon others but to separate ourselves from them.

David Mills writes from Pennsylvania.