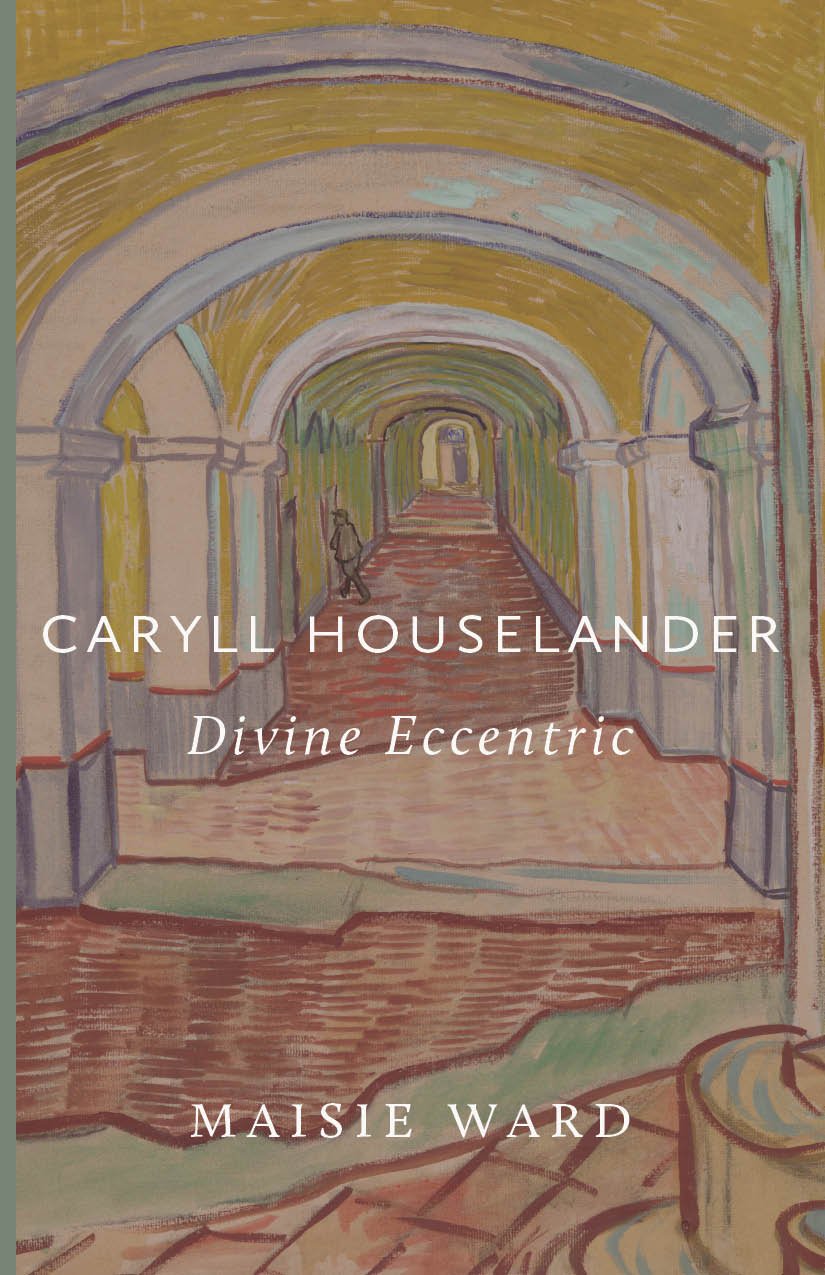

When Maisie Ward, in her biography of Caryll Houselander, called her “that divine eccentric,” Ward knew what she was talking about. Although divinity was up to God, there was no question that Houselander was eccentric. And, as Ward, her friend and publisher, knew, Houselander was also one of the finest spiritual writers of modern times.

Along with a rare gift for words, she possessed a no less remarkable talent for empathy with suffering people. “She loved them back to life,” a psychiatrist said of her way of approaching the sick. Partly, that may have arisen from her own frequent suffering. Certainly, it reflected the fact that — quite literally — she saw the suffering Christ in others.

–Early lessons

Caryll Houselander was born Sept. 29, 1901, in Bath, England, one of two daughters of religiously nonpracticing parents. When she was 6, her mother had her and her sister baptized as Catholics before entering the church herself sometime later. Years after, she was to title her autobiography “A Rocking-Horse Catholic” — in contrast with “cradle” Catholics who were such from infancy.

When she was 9, her parents separated, and her mother sent her to a convent school. Her five years there were largely happy ones, and it was there, too, that she experienced the first of what appear to have been mystical experiences.

While most of the nuns were French, one was a Bavarian woman who was isolated from the rest of the community by her language and — French-German animosity being at its peak as World War I raged — by her nationality. One day, Houselander came upon the woman weeping as she polished shoes by herself. Not knowing what to say or do, the child stood in silence. She wrote:

“At last, with an effort, I raised my head, and then — I saw — the nun was crowned with the crown of thorns. I said to her, ‘I would not cry, if I was wearing the crown of thorns like you are.’ I sat down beside her, and together we polished the shoes.”

After a long stretch of ill health, one of many such that she was to suffer, her mother sent the 15-year-old girl to an English convent school. In this new setting, Houselander — by now “a confirmed prig and morbidly shy” — was repelled by “the sportiness and heartiness, the healthiness and wealthiness, of nearly all my schoolfellows.” Not surprisingly, she made no friends.

It was here, too, that her generally negative view of things began to include the church.

“There was a dangerous tendency in my mind,” she writes, “to separate the idea of Our Lord and the Blessed Sacrament from the idea of the church. … I knew very little about the Mystical Body of Christ. I was more and more inclined to think of the church as the hierarchy, bishops and priests, and as a rather rigid authority; I certainly did not know that, in Christ, I myself was as much a part of the church as the pope.”

–A king’s crown

Eventually her mother, by now living in London and operating a boarding house to support herself and her daughters, brought Caryll home to lend a hand. One evening in July 1918, on an errand to buy potatoes for dinner, she had a spectacular new vision. Filling the sky was a gigantic Russian icon of Christ the King crucified.

Although she did not know it at the time, only hours before her experience, the Russian Czar Nicholas II and his family were executed by Bolshevik revolutionaries. A day or two later, she saw the murdered Czar’s face for the first time in a newspaper photograph — and it was the face of the crucified Christ whom she had seen in her vision.

“It was not for nothing,” she wrote, “that my first glimpse of Christ in man was in the humblest of lay sisters, bowed by a great crown of thorns, and my second a king in splendor, bowed under a great crown of gold. I realized that every crown is Christ’s crown, and the crown of gold is a crown of thorns.”

–A life-changing vision

Time passed. Houselander attended art school, left home, quit the Catholic church. She looked into other Christian churches as well as Judaism and Buddhism, but none of them seemed right for her. Meanwhile, she eked out a living at odd jobs and eventually as a commercial artist, while pursuing a bohemian lifestyle that included falling in love with a professional spy who broke her heart by marrying another woman.

One day in Hyde Park, she stopped to listen to a young outdoor speaker from a group called the Catholic Evidence Guild. The man was Frank Sheed — author, apologist and, with his wife Maisie Ward, destined to be Houselander’s publisher. Almost despite herself, she was impressed by what she heard him saying.

“It was the Catholic church,” she wrote, “but it was the church being Christ; not waiting for the people to come in, but coming out to the people. It was really, in a way that I could not understand, Christ following his lost sheep — of whom I was one.”

Soon after, Houselander’s turning point arrived — the event that, she said, “altered my life completely.”

“I was in an underground train, a crowded train in which all sorts of people jostled together, sitting and strap-hanging. … Quite suddenly, I saw with my mind, but as vividly as a wonderful picture, Christ in them all. But I saw more than that; not only was Christ in every one of them, living in them, dying in them, rejoicing in them, sorrowing in them, the whole world was here, too, here in this underground train; not only the world as it was at that moment, not only all the people in all the countries of the world, but all those people who had lived in the past, and all those yet to come.”

The “vision” lingered for several days, then faded, but its impact remained. “Realization of our oneness in Christ is the only cure for human loneliness,” she said. “For me, too, it is the only ultimate meaning of life, the only thing that gives meaning and purpose to every life.”

–‘Let me receive the cross gladly’

Houselander returned to the church. Soon she began writing, exploring the rich implications of the image of the church as Mystical Body of Christ. Her first book, “This War Is the Passion,” came out in 1941 in the darkest days of World War II and explored this theme. Other books, many in print today, followed in a steady stream from the Sheed and Ward publishing house.

When she died of cancer at age 53 in 1954, Msgr. Ronald Knox, author, homilist and translator of the Bible, said of her, “In all she wrote, there was a candor as of childhood; she seemed to see everything for the first time, and the driest of doctrinal considerations shone out like a restored picture when she had finished with it.”

But leave the summing-up to Houselander. In a volume called “The Way of the Cross,” she prays to Jesus:

“Lord, let me receive the cross gladly; let me recognize your cross in mine, and that of the whole world in yours. …

“Let me realize that because you have made my suffering yours and given it the power of your love, it can reach everyone, everywhere — those in my own home, those who seem to be out of my reach — it can reach them all with your healing and your love.

“Let me always remember that those sufferings known only to myself, which seem to be without purpose and without meaning, are part of your plan to redeem the world.”

Spoken, you might say, like a genuinely divine eccentric.

Russell Shaw, a veteran journalist and writer, is the author of more than 20 books, including three novels.