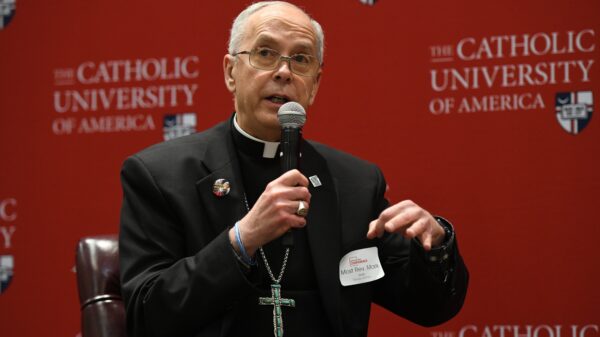

SAN QUENTIN, Calif. (OSV News) — San Francisco Archbishop Salvatore J. Cordileone said a recent daylong pastoral visit to death row at San Quentin State Prison with three other California bishops confirmed for him “there is a deep spiritual thirst” among those imprisoned there, “and a desire of the men to grow in their knowledge of the Catholic faith.”

The visit to death row “was especially heart-wrenching, but even there, I saw a desire for a deeper spiritual life,” he said in a reflection on the March 7 visit shared by the California Catholic Conference in a March 14 email newsletter. Archbishop Cordileone’s and the other bishops’ reflections also were provided to OSV News.

“One of the condemned is even a Benedictine oblate, who renews his vows annually with the prison chaplain,” the archbishop wrote. “And all this despite the very oppressive conditions: a cell about 5′ x 15′, with a sink, a toilet and a table that doubles as a bed. They are confined in that space most of the time. And yet, the ones we spoke with were happy to see us and very conversant.”

The other prelates who visited the prison were Bishops Michael C. Barber of Oakland, Oscar Cantú of San Jose and Jaime Soto of Sacramento. The bishops heard confessions and spoke with inmates in the prison’s general population, as well as on death row. The men talked about “their unexpected trials, spiritual conversions and faith life while incarcerated,” the Catholic conference’s newsletter said.

Deacon John Storm, director of Restorative Justice for the Diocese of Santa Rosa, who also was in the delegation, said he was moved by testimony from one inmate in particular “who described a personal encounter with Christ engendered by his participation in programs sponsored by the Catholic chapel.”

“That encounter led him to drop out of the gang culture, where he was previously a leader or ‘shot-caller,’ and to seek a new life of discipleship to others,” the deacon said.

The visitors were required to wear a bulletproof vest while visiting death row, or the “East Block,” which Gov. Gavin Newsom has promised to dismantle following his moratorium on executions in the state.

The prison complex sits on Point San Quentin, a 432-acre parcel of land on the north side of the San Francisco Bay. It has California’s only death chamber.

California, which last carried out an execution in 2006, is one of 28 states that maintain death rows, along with the U.S. government, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. In early January 2023, corrections officials said this year the state will start to move all inmates into the general prison population. As of Jan. 9, 671 male inmates are housed on San Quentin’s death row.

In his reflection, Archbishop Cordileone said that in his conversations with inmates in the chapel, he was “struck by the men’s sensitivity to the sacredness” of that space.

San Quentin “is one of the few prisons in California to have a dedicated Catholic chapel,” he noted, “and the men very much respect that sacred space, and feel aggrieved when others violate that sense of sacredness by irreverent behavior.”

“The ones I spoke with are very interested in what is happening in the church, in Rome and throughout the world, and would like more access to information on that,” the archbishop said. “They are also very earnest in their desire to learn more about the faith in order to defend it against some of the inmates who criticize Catholic beliefs. They emphasized the need for more apologetics.”

“As I told them, I often tell people ‘on the outside,’ who have no knowledge of what it is like in a prison, that ‘Jesus is alive and well behind bars,'” Archbishop Cordileone added.

Bishop Soto described conversations with inmates in the North Block as “unique and personal.” This cell block, along with the West Block, houses the general population. Until the COVID-19 pandemic, the South Block served several functions, including as a reception center for the intake of prisoners from county jails.

“There was little reference to the awkward circumstances of speaking through bars,” the bishop said. “Worries about their family, questions about Scripture, curiosities about the world outside, and interesting books, filled our conversations.”

“My brother bishops and I finished our visit hearing the confessions of men from the other parts of the prison, the ‘general population,'” he continued. “There was a palpable hunger for the particular grace of the sacrament of penance. God’s infinite mercy is revealed in the humble, human matter of a personal conversation. There was also a sacramental dimension in the conversations through the bars of ‘North Block.'”

He added, “Even in the institutional restraints on those simple human encounters, the powerful divine mercy of Jesus continues to make the Incarnation a redeeming encounter with God.”

Bishop Barber praised the pastoral work being done by San Quentin’s full-time Catholic chaplain, Jesuit Father Manny Chavira, but he noted that after visiting and celebrating Mass at San Quentin for more than 20 years, he “was appalled to find the Catholic Chapel of Our Lady of the Rosary repurposed by the state as a “nondenominational meeting space.'”

The Catholic chapel was consecrated in 1960 and is furnished with a marble altar, communion rail, and side altars dedicated to the Sacred Heart and Mary.

“We want the inmates to feel they were not in prison but in a real Catholic parish when they attended Mass and other services. Then they would be inclined to continue the practice of their faith when they left prison,” Bishop Barber said.

He commented that the state had recently changed the name of the California Department of Corrections to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

“How does the state think they can rehabilitate these men while downplaying the role of faith in their lives?” Bishop Barber asked. “I believe the state of California could benefit from studying how spiritual resiliency contributes to the rehabilitation of inmates.”