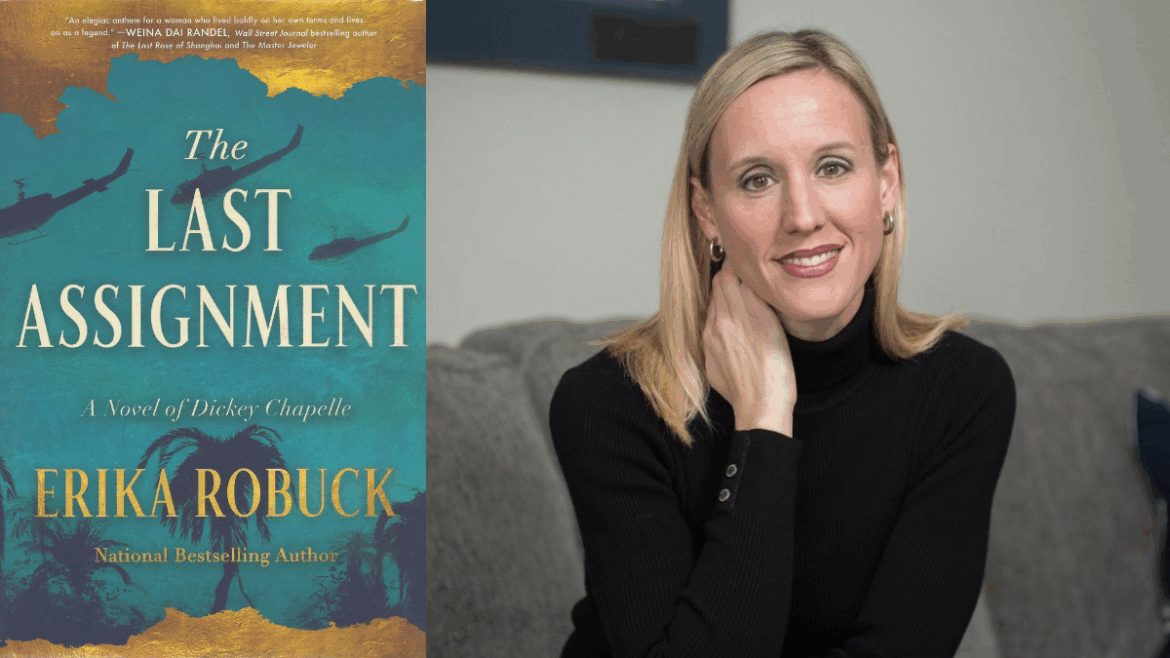

Maryland-based author Erika Robuck‘s latest novel, “The Last Assignment,” can be seen as a continuation of the writer’s niche area, namely, celebrating the achievements of strong, independent heroines whose exploits cry out for some form of recognition.

Released in August 2025, the book outlines the life and work of photojournalist/war correspondent Louise Georgette “Dickey” Chapelle, who was killed in November 1965 while accompanying a platoon of U.S. Marines in Vietnam. She is considered the first female reporter to be killed in action.

The ambitious, forthright Wisconsin native overcame a raft of taboos about women working in men’s roles to live her dream of revealing the horrors of war through story and picture.

The story for Robuck serves as an inspiration for impressionable readers. “I would like readers to see that finding one’s vocation and doing what we are made to do brings peace and joy,” Robuck said in the author’s notes to the book. “In spite of harrowing circumstances, Dickey knew she was living her calling and was doing so — in spite of mistakes along the way — with integrity. She always had hope, and that hope was for peace. It is my deepest prayer for the world.”

“The Last Assignment” follows closely on the heels of Robuck’s 2024 work “The Last Twelve Miles,” the story of Florida-based “rum runners” in the prohibition era. She is an emerging master of the “bio-fiction” subgenre, an offshoot of the more established historical fiction category.

Author Erika Robuck stretches historical fiction genre in new directions

What sets Robuck apart from many of her contemporaries is the exhaustive research she undertakes to get fully “into the minds” of her protagonists, most of whom are real people, and not creations of an author’s imagination.

Her 2013 novel, “Call Me Zelda,” for example, is replete with dialogue between Jazz Age writer F. Scott Fitzgerald and his troubled but artistically gifted wife Zelda Sayre. Some contemporary authors might shudder at having to speak in the voice of a literary master like Fitzgerald, but not Robuck.

“I enjoy dialogue and do not find it a challenge because I don’t start writing until I thoroughly know my subjects,” Robuck told OSV News. “I research for at least six months before starting the first draft, and only start writing once I’ve read everything about and by the subject. Once their voices and personalities are firmly in my head, I begin the novel. During revisions, I read the dialogue out loud to make sure it rings true.”

In some ways, Robuck is stretching the historical fiction genre in new and positive directions. “Someone recently told me I write ‘bio-fiction’ — a fusion of biography and historical fiction, and I like the sound of that,” she said. “The value of taking on the life of an historical figure in novel form allows the reader a more human and sympathetic experience of the life of the subject and the times and places in which they lived. That feels more immersive to me than nonfiction.”

“The unifying power of ordinary people doing extraordinary things” seen in Robuck’s work

But in addition to being as historically accurate as possible, Robuck embraces occasional contrivances and fact changes to facilitate the narrative flow. She admits to using “the crumbs” of historical figures’ lives to piece together engaging suspense, intrigue and resolution. It’s the author’s attempt to have readers gain sympathy for the tribulations and suffering of her protagonists.

“While I may use details, personality traits or events in creating my characters, none of them is a perfect representation of a living acquaintance,” she said. “Also, my mission is one of redemption, especially of these tortured, dead writers. I feel connected to them and wish for their ultimate peace. My writing is a prayer to them.”

Robuck’s most popular novel to date is “The Invisible Woman” (2021), the story of little-known Maryland native Virginia Hall, who during the Second World War became a member of Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE) and went to Nazi-occupied France to organize resistance efforts.

“‘The Invisible Woman’ seems to appeal to men and women, young and old. Virginia Hall is a superhero. If I had made up this story, it would have been unbelievable,” Robuck reflected.

In addition to paying homage to an unsung American heroine sacrificing for justice and world peace, this book allowed Robuck to explore another deeply held conviction — to celebrate through fiction the unifying power of ordinary people doing extraordinary things.

Catholic upbringing informs Robuck’s worldview, work

But as a cradle Catholic with a strong commitment to the expectations of the baptized, Robuck has other ambitions at play.

After exchanging a teaching career for the writer’s life, Robuck realized bio-fiction had more rewards than first expected. While keeping alive the struggles and sacrifices of real people doing quietly heroic things, her later stories emphasize the importance of grace and redemption for all human characters, the great, the suffering, the celebrated and the unknown.

This, in turn, allowed Robuck to infuse some of her work with moral guidelines learned from a strongly Catholic upbringing. “My compulsion to write was present long before the grace of deepening faith, but at this point in my life, I consider myself a Catholic writer, and a Catholic before any other descriptor … wife, mother, teacher,” she said. “My heroines are not Catholic, nor should it be assumed that they are. I am Catholic, so that shapes my lens. From this, my readers can be assured, the older I’ve gotten, and the more my faith has deepened, the more ‘Catholic-friendly’ my work has become.”

Many of Robuck’s strongest Catholic convictions, the importance of confession, the search for grace and the unceasing opportunities to find redemption, can be found in her more recent fiction. Some of her books feature priest figures who dispense spiritual advice and inspiration in profound ways.

In “The Invisible Woman,” a French nun working with the resistance, reminds heroine Virginia Hall of the healing quality of honest confession: “The priest stands in for our Lord. He’s a channel of the grace of forgiveness. … “Speaking (your sins) aloud to another is deliberate. It requires premeditation. It makes you more mindful of your sins and unburdens you. And the Lord gave his apostles the authority to bind or loose us from our sins.”

Similarly, in “Call Me Zelda,” the heroine Anna, a psychiatric nurse working with the emotionally unstable Zelda, asks her priest brother what is to be gained by the sacrament of confession: “Confession is the clearest way to unburden ourselves and grow in our spiritual and overall health.”

Robuck’s emphasis on reconciliation and a stoic attitude in response to pain and suffering are not confined to her fiction. Her experience as a writer, teacher and parent, coupled with insights gained by exploring the thoughts of actual historical figures, have sharpened her views on overcoming injustice and community cohesiveness.

“The seeds sewn from 12 years of Catholic education are coming to fruition,” Robuck said. “I believe the current crisis of mental health and drug addiction … and all strife from sin in the world could be radically reversed if Catholics returned regularly to the sacrament of reconciliation.”

For Robuck, real healing requires a return to such social basics and sensitivity, awareness and understanding. Without healing, Robuck believes, one cannot receive the “full grace” of the Eucharist.

Future books in the works for the Catholic author

As the newly released “The Last Assignment” book is making the rounds in newspaper reviews and book club discussions, Robuck is already making plans for her next two novels. The first deals with another woman “in the shadows of intelligence history,” while the second will be based on the author’s discovery of both savory and unsavory characters in her ancestry.

However these new works turn out, they are almost certain to champion many of the causes especially dear to the writer’s imagination.

“Some of the themes that I hope resonate with readers are the depths of true friendship, the danger of using others and the power of confession and atonement,” she said. “I also want to explore the concept of how beautiful we can become if we first go through trials and allow ourselves to be transformed and purified.”

Michael Mastromatteo is a writer, editor and book reviewer from Toronto.