Before COVID hit, I had been spending my Tuesday nights serving food outside a homeless shelter in midtown Manhattan. Erica, one of the regulars, will always stand out in my memory. One night, she asked me for one of the rosaries lying on the table next to the food and drinks.

“You’re going to use that to pray for me, right?” I asked.

“Why do you think I’m taking it? Of course! I gotta pray for you.”

Erica and I had been sharing more of our life experiences with each other as time went on. After her husband died three years ago, she’d been in and out of jobs. She was let go from her last one because a back injury made it too difficult for her to work.

As much as she’s not a fan of the way that particular shelter was run, she continued to go to it because of the relationships she’d formed with the people there. “They’ve become my little community.” And that’s saying a lot.

The shelter is always cold (they blast the air-conditioning, regardless of the temperature outside), and it has no beds, only chairs to sleep on. The patrons have limited time to use the bathroom and showers, and they are expelled at 5:30 in the morning, having to beg for food or work a job that severely underpays them.

On top of that, many of them are up against injustices that are deeply ingrained in the structure of our society. Many are immigrants without documentation, women who have faced abuse, and people of color who were fired from jobs because of racial prejudice.

Some people serve the poor out of a sense of benevolence or moralistic duty, often proclaiming that it makes them feel good about themselves.

But how “good” of a deed is giving a homeless person a plate of pasta, anyway? When I look at all these factors they’re up against, I realize I’m not making much of an actual difference in their lives.

Others say that works of charity are useless, insisting that we ought to focus our energy on taking political action so as to make the system more just for the underprivileged.

Whether you approach the problem of poverty from a position of charity, political action or a combination of the two, being face to face with someone who is homeless makes you realize how little you have to offer. Nothing I do will fully “save” this person. Each person has their own set of experiences, pains, needs and desires, which I may never fully understand.

When serving, I find that I have a lot more questions than answers: Who are these people, and what are their stories? How do they find hope and meaning amid their everyday circumstances? While I am extremely privileged and may never have to worry about where my next meal is going to come from, I do experience myself to be needy, to be hungry and thirsty, in other ways. I also want to discover meaning in my everyday circumstances — and, oftentimes, it’s the homeless who have more to offer me in this regard. My spiritual “neediness” is a point of commonality between me and the people I serve.

Part of living in the front row includes a sense of having evolved beyond antiquated or even backward beliefs and attitudes toward life: “Most of us in the front row had decided that it was impossible to identify absolutes, that moral certainties were suspect, and that all that we could know or value was what science revealed to be quantifiable. Religion was an old, irrational thing that limited and repressed people — and often outright oppressed them.”

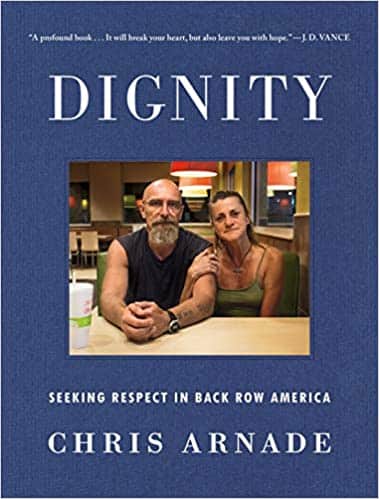

After several years on Wall Street, Arnade was feeling disillusioned with his lifestyle. He started going on long-distance walks around New York City to clear his mind. One day, out of curiosity, he decided to take a walk to Hunts Point in the Bronx, a neighborhood that was stigmatized by his co-workers for being “too dangerous and too poor.”

It was then that he started to see “how cloistered and privileged my world was — and how narrow and selfish I was.” This visit inspired him to leave his job and to explore “Back Row America” — the name he uses to refer to forgotten cities that suffer from high rates of poverty, joblessness, racism and drug abuse. He finds that these cities tend to have two gathering hubs in common: McDonald’s and churches. He writes:

“Often, the people using the McDonald’s were the same people using the churches, people who sat for hours reading or studying the Bible at a booth.

“When I first went to the Bronx, I expected that the people there, those most affected by the coldness and ruthlessness of the world, would share my atheism. Instead, I found a strong belief in the supernatural, and a faith that manifested in many ways, mostly as a belief in the Bible.

“For many back-row Americans, the only places that regularly treat them like humans are churches. … They walk inside the church, and immediately they meet people who get them.”

While Arnade claims not to have experienced a conversion, he has learned to appreciate and respect the faith of the people he’s met on his visits.

Arnade’s words echoed my undergraduate experience at an elite private university, where social justice was the main focus of class discussions and extracurricular activities. We were taught to check our privilege at the door and to shake off our savior complex.

When attending service and advocacy events with my classmates, many had a hard time facing the people whose cause they desired to support. No matter how many times they told themselves they weren’t saviors stooping down from their position of superiority to fix the problems of the needy, they had a hard time talking freely and openly with the people. That invisible wall dividing the privileged from the underprivileged, the “evolved” from the “still evolving,” as much as they tried sincerely to regard the others as equals, became an obstacle keeping them from experiencing unity and intimacy with them.

I saw the wall thicken every time the underprivileged brought up religion. Comments such as, “I know God’s got me in his hands,” or “the problem with the world today is people want to worship themselves and ignore God’s word,” would leave them smiling and nodding on the outside, while on the inside they were cringing, attempting zealously to stuff away their condescension for feeling like they have evolved beyond such antiquated beliefs.

My experience of faith helps me to recognize that no matter how much money, education and material goods I have, I am not superior to the poor. Not because of some abstract notion of equality, but because it concretely brings me face to face with the fact that any material wealth I might have doesn’t make me “richer” than anyone. At the end of the day, I am a sinner in need of God’s mercy, too.

While I may never be able to relate to the experience of being in and out of the shelter system, of lacking food and other necessities, or of the burdens of systemic racism, I can relate to homeless people’s desire for God — not only that, but I can learn about it from them. One doesn’t have to be religious to communicate openly and develop relationships with those who are underprivileged, as Arnade demonstrates, but I do think it is crucial to learn how to be humble and listen.

The book echoes the distinction Father Greg Boyle, founder of Homeboy Industries, makes between “taking the right stand on issues” and “standing in the right place — with those relegated to the margins.” The former assumes that the back row is in need of solutions that the front row can offer them. But can I claim to fully know what the other truly needs?

Arnade dropped the idea that education and reliance on the hard “facts” proven by the social sciences give access to totalizing “solutions.” He stepped back from his position of only “supporting” the poor through voting for the right politicians and policies and actually got to know people’s stories by listening to and spending time with them.

The Peruvian theologian and philosopher Father Gustavo Gutiérrez once said, “You say you love the poor; name them.”

While structural and political changes are indeed necessary, those who are more privileged than others ought not to forget to start with what’s most basic: encountering the other and living in solidarity with them. Arnade shows us that the first step is learning a person’s name. The rest will follow.

Stephen G. Adubato writes from New Jersey.