The standing tradition of many monastic houses for centuries was the art of copying Sacred Scripture and other desirable manuscripts. The calligraphy that stemmed and sprang from these monasteries and priories are considered some of the world’s most precious and valuable articles. With the custodianship of this “manuscript culture,” monks produced some of the most beautiful literary art in the world: glowing and intricate margins of floral arrangements and thousands of lines of words painstakingly handwritten with such consistency that appear as if they, too, were produced from a press.

And the printing press is what effectively ended this tradition and art. No longer cost or time effective, nor completely necessary, handwritten manuscripts fell out of favor and largely fell out of practice. But there is a monastery in the north of Italy that has maintained the value of the scriptorium and have adapted the skills of their predecessors with technology of the modern age for a fresh mission. With their bounty of products that support their lifestyle, such as soaps, wines, oils and religious articles, the Benedictines of the Praglia (prah-liah) Abbey are the masters of il restauro del libro, or “the restoration of the book.”

Praglia Abbey, as most religious houses in Europe, has a broken history. Fourteen miles south of Padua, the monastery was founded in 1080 under the oversight of the much larger St. Giustina Abbey in Padua, where the evangelist Luke and the apostle Matthias are still entombed. From the 14th-16th centuries, the abbey became more independent and increased in its size, rebuilding its small monastery into a massive complex and church, now a basilica decorated by some of the best Renaissance artists of Veneto. But with the restrictions of the 1810 Napoleon laws, the Abbey was outlawed, disbanded and closed. The normal practice of the time was to use the monasteries as horse stables and barracks or storage depots. Sources say that a monk or two may have stayed as custodians, but most of the abbey’s religious items, décor and art were looted or privately kept elsewhere, lost to the age with no record of whereabouts. Monks did not return until the early 20th century, and since then it has thrived once more.

As mentioned, Praglia are among the foremost in the world on book restoration, extending to the restoration of letters and drawings. They earned the world’s respect and admiration in 1966 when the Arno River flooded Florence, wrecking and destroying innumerable pieces of property to include private art and libraries of books. Within days of the flood, thousands of these books were delivered to Praglia Abbey for immediate assessment, preservation and restoration. Praglia’s expert teams of monks and lay specialists returned the books to Florence in better shape than they were before the flood. They’ve restored folios of letters of St. Francis, Galileo and a slew of popes, dukes and other religious and political figures.

I discovered them in late 2019 when a friend brought me a bottle of wine and a brochure. “Hey Shaun. You should check out these monks near Padova. They make all sorts of crafts, and you can even stay there overnight. Sounds like something you’d like. They also repair old books or something.”

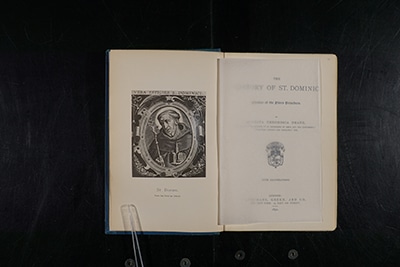

Wine and honey? Great. Overnight sojourns, retreats and pilgrimages? Even better. But at the time, I was also in possession of some pretty beat up books: biographies of two of my favorite saints. I had recently purchased two used copies of Augusta Theodosia Drane’s hagiography on St. Dominic from 1857, first edition, and also a late 1800s biography of St. John of the Cross. They came (and I accepted them) in a tattered shape, but I still read one of the Dominic copies. After day trips here and family vacations there, and maybe an accidental handling from a toddler, the condition of these books became worse and worse. I contacted the Abbey around January-February 2020, and had the books assessed.

I’ll never forget: I also brought a small Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the priest in charge said, “This isn’t so bad.”

I replied, “What sort of books do you usually accept?” And he laughed.

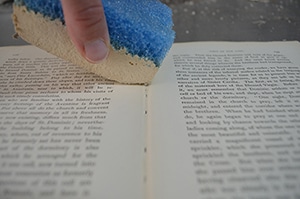

“But these,” he grabs the saint books, “these are very worn and should be repaired.” And I finally breathed. All of these books were in the same general condition: cracked and broken spines, sections of pages loose or torn out (but not missing, thankfully), stains on pages and ripped corners.

Of course, COIVD-19 hit. The Abbey is located not far from Vo’ — now world famous — the small Italian town where many of the first cases stemmed from. Patience was my ally: I knew this restoration was a long process, requiring months of steady handwork, but I had wondered if the work would be completed at all. The individual in charge assured me progress was being made.

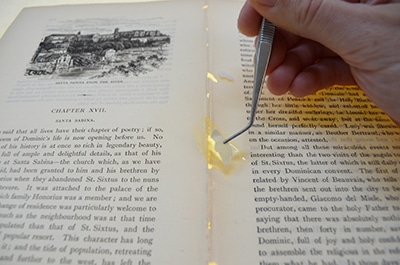

The final product shows the intricate and dexterous work of the laborers who hand-stitched the binding and pages, re-replaced the paper missing from years of dilapidation, and repaired holes and tears, all with a great detail poured into cleaning and sprucing up each page and cherished image of the saint.

The work is laborious, but the final product is absolutely stunning. They used the finest Japanese paper, natural glues that won’t crack and stain over time, and high quality materials for the integration of the binding and spine and protective pages for images.

I was thrilled beyond words to receive the books in mid-July. The documentation that accompanied the books is also something I’ll treasure forever. I don’t just have repaired books to last another few generations of Catholics in my family: I have certification that my books were repaired according to a tradition that spans generations of monks who have labored in the manuscript culture. For this, I’m truly grateful, and I can’t put a price on it.

There’s a poetic object I’ve noticed in the history of the Praglia Abbey. The restoration expertise of the Abbey is a hallmark, not just for their incredible workmanship, but also because it reflects the history of the abbey itself: The monks are not just the restorers of the tradition of manuscript culture through book restoration, but are the restorers of their monastic rule through their remnant revival of the monastic lifestyle. As each book is improved, so are the vocations of the monks.

Shaun McAfee writes from Italy.