Orders of nuns are doing the same thing. They held slaves prior to 1866, and they are coming to terms with the fact that they owned, bought and sold slaves. Even Catholic laity are facing the past. Trying to make amends for his ancestors, one wealthy Catholic recently made a substantial donation to a traditionally African-American college.

For Catholics, reading the history from that period is uncomfortable. Abolitionists were many — the Grimke sisters in South Carolina, William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, from Maryland — but no Catholic is prominent among them.

At times, the uninformed excuse is given that no Catholics were in positions of influence at the time. Not quite. Catholics ran Louisiana, a center of the slave trade, politically, socially, economically and in every other respect.

Catholics were major players in Maryland, a slave state, although it did not leave the Union. Catholics had a presence in St. Louis, in Missouri, another slave state that did not join the Confederacy. Catholics were strong in Charleston, South Carolina, and Savannah, Georgia.

In the cabinet of Confederate President Jefferson Davis were Secretary of the Navy Stephen R. Mallory, a Catholic from Pensacola, Florida, and Secretary of State Judah Benjamin, a Jew from New Orleans, whose wife was a staunch Catholic. Confederate General Pierre Beauregard and Admiral Raphael Semmes were Catholics.

The only chaplain killed in action in the Civil War, of any denomination, was a priest from Nashville, Father Emmeran Bliemel, serving in the Confederate Army.

This is the obvious fact. Catholics accepted slavery in many, many cases. After all, they likely reasoned, under the Constitution and laws of the United States, that slavery was perfectly legal. (Slavery was not a Southern institution; it was an American institution.)

They probably also thought that many Americans, if not a majority of Americans, accepted slavery. (They took no polls in those days, so we do not know for sure who or how many supported or at least tolerated slavery, but it is clear that Americans universally did not oppose the system.)

So, Catholics back then rolled with the tide. Now we say that it was unbelievable, but, after all, it was back then. Historically, while slavery may have been “back then” in our country, rolling with the tide is as alive and well as ever for many Catholics today in this country. Only the issues are different.

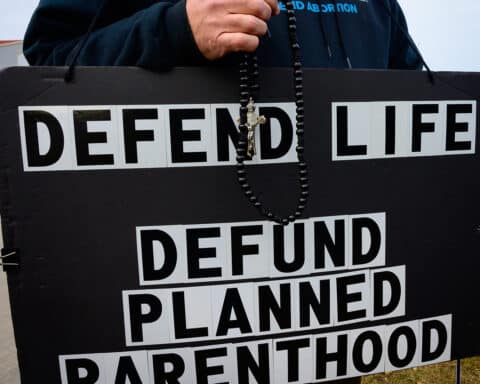

Since 1972, when the United States Supreme Court invalidated the laws that made abortion illegal, the Catholic Church in this country, led by several succeeding generations of bishops, has been the most vocal and most constant voice in denouncing abortion as a grave evil.

Anyone who claims not to know where the Catholic Church stands on abortion just arrived from Mars or is utterly oblivious to fact.

Nevertheless, so many American Catholics, even though they may not disagree with Church teaching regarding the immorality of abortion, simply tolerate it. They do not hold politicians to account on the issue, for example. They even may tolerate it when it occurs in their own families.

Abortion is one concern, but the list of evils and sins is long in this country. Other problems may be our society’s chronic racism, mistreatment of people because of their condition or circumstance, the rampant sexual abuse of women and of children — and I do not limit this accusation to clergy — exploitation of people here at home or abroad, and on and on.

What can we do? We can refuse to participate in certain behavior, obviously, and we can make our opinions heard, explaining why we accept our Church’s teachings, because it is from God, and it makes sense.

We live in a society troubled by misinformation and even bad intentions.

Msgr. Owen F. Campion is OSV’s chaplain.