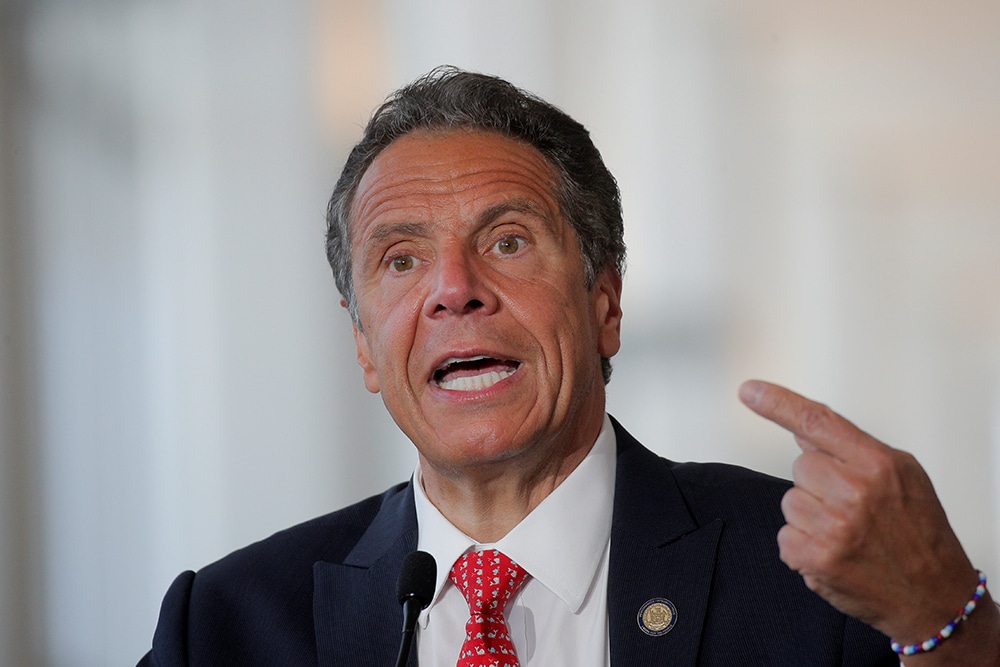

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo resigned Tuesday, days after the highest law enforcement office in the state released a detailed report chronicling allegations of sexual harassment.

One supposes it theoretically would have been possible for him to survive a trial, or even that he might have avoided impeachment, but he had lost the confidence of his own party, and citizens overwhelmingly believed he should resign.

It’s important to keep in mind that the questions of illegal and even possibly criminal conduct are quite distinct from those regarding the facts of the case and their weight in the minds of New York citizens and legislators. Judicial processes are apt to determine whether Cuomo’s conduct was criminal. His political fortunes are subject to political processes in which leaders are imperfectly but still meaningfully beholden to the people.

Whether Cuomo or anyone else broke the law or behaved criminally is one set of questions, in other words. What it appears certain Cuomo and others did (or failed to do), and what the effects of their actions and omissions had on the leadership culture within New York state, is quite another. Cuomo’s political fortunes and personal reputation will depend on the latter as well as the former. The system isn’t perfect, but it appears to be working tolerably well this time around in New York.

When one looks at how the Church has investigated bishops suspected or known to have committed wrongdoing, one struggles to make a worthy comparison. For one thing, there is no independent investigative arm to speak of, no truly independent judiciary, no stable mechanisms for either process or transparency.

The closest one gets in recent times is the investigation Archbishop William E. Lori of Baltimore commissioned into Bishop Michael J. Bransfield and his conduct — personal and official — while he led the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston, West Virginia.

Pope Francis accepted Bishop Bransfield’s resignation within a week of Bransfield’s 75th birthday — the age at which bishops are required to offer their resignations — and tasked Archbishop Lori with organizing an investigation, in what eventually became something of a dry run for the pope’s “metropolitan model” of bishop accountability.

Investigators conducted that probe and prepared a 60-page report of Bishop Bransfield’s 13 years in West Virginia, which went to Pope Francis. The faithful and the general public got their first look at the findings of the report when they leaked to The Washington Post and only saw the report itself when the newspaper decided to publish it.

Archbishop Lori had pushed for significant transparency, including the release of the dossier, but didn’t have much luck. It’s also worth recalling that Bishop Bransfield was generous with diocesan money — which he frequently passed as his own, by writing checks drawn on his personal account and then reimbursing himself from diocesan coffers — and frequently showed his generosity to senior churchmen. Many of these were powerful and highly placed, including Archbishop Lori himself, who redacted the names of the churchmen who received money from Bransfield, including his own. In the real world, failure to disclose something like that will certainly get you taken off a case, at best.

The 168-page report from the New York attorney general, on the other hand, was immediately available to the public. It sets out the AG’s legal authority to investigate, explains the investigative procedure the AG’s office adopted and pursued, presents findings of fact and law, and offers conclusions.

The governor’s behavior “constituted sexual harassment under federal and state law,” that “the executive chamber’s failure to report and investigate allegations of sexual harassment violated their own internal policies,” according to the AG.

The AG’s report says the governor and his administration responded to at least one harassment report in a manner that “constituted unlawful retaliation.”

Perhaps the most important finding was that “the culture and environment in the Executive Chamber” — the governor’s powerful inner circle of senior officials and trustiest advisers — “contributed to the conditions that led to sexual harassment and the problematic responses to allegations of harassment.”

The report also found that the climate throughout the leadership culture of various key New York agencies and departments was — is — pretty rotten, owing at least in part to the knock-on effects of the culture the governor fostered. “[T]his culture of intimidation and retribution were not limited to those within the Executive Chamber,” the report said.

“Many witnesses,” the AG’s report found, “including those who worked at other New York State agencies, including the New York State Troopers and elsewhere, described interactions that they perceived to be threatening and bullying to the extreme.”

“Indeed, most witnesses–again, other than those with close ties to the Chamber’s leadership– expressed concern and fear that providing any negative information to us in our investigation would lead to harm and retribution.”

“Their trepidation,” the finding continued, “arose from the way in which they observed the Executive Chamber respond to anyone who might do or say anything that was damaging to the Governor.”

“Their fear,” the report continued, “was exacerbated by the recognition that, as Governor of New York, he remained extremely powerful and that he was known to have a ‘vindictive’ nature.”

All that tracks pretty closely with Bransfield’s official behavior as detailed in the Lori report.

Bransfield’s personal conduct was more egregious in both degree and kind — he sexually assaulted people and abused alcohol frequently — but the one common element, the fil rouge running through both the Lori report and the New York AG’s report, is the fear — the amply founded certitude — of reprisal from the top.

There are civil mechanisms in place — political, constitutional, judicial — for dealing with officeholders who abuse the public trust. The Church has no similar political structures in operation. The few judicial structures there are exist mostly on paper and are subject to the will (the whim?) of an absolute ruler. The twofold concern of the men who govern the Church all too often appears to be avoiding trouble and pleasing the superior authority. That does not bode well for root-and-branch reform efforts in the short and intermediate term. It promises to be disastrous, in fact, and likely sooner rather than later.

For that, the best illustration is the unfortunate handling of Bishop Michael J. Hoeppner of Crookston, Minnesota. The short version of that very long and very sad story is that Hoeppner resigned as bishop of Crookston at Pope Francis’ request, following an investigation under Pope Francis’ signature reform law, Vos estis lux mundi, of claims Hoeppner “had intentionally interfered with or avoided a canonical or civil investigation of an allegation of sexual abuse of a minor.”

There is no official word on the specifics of that alleged cover-up. Archbishop Bernard Hebda of St. Paul and Minneapolis — universally recognized as an extraordinarily capable canonist and by-the-book investigator — conducted the inquest.

No Church jurisdiction or authority has published the investigation reports. No churchman has said whether Bishop Hoeppner ever faced formal canonical charges as a result of the investigations. No Church official has said whether Hoeppner was tried, or whether he would have been had he refused to step down. Hoeppner remains in good standing, as far as anyone knows from official sources.

If the Bishop Hoeppner affair is any sort of bellwether, the churchmen appear content with the opaque status quo.

A case like that of Bishop Nicholas DiMarzio of Brooklyn, New York, also merits consideration. A Newark, New Jersey, fellow who served under laicized former cardinal Theodore McCarrick, Bishop DiMarzio has been under Vos estis investigation for more than a year and a half, in connection with at least one allegation of abuse of a minor stemming from the 1970s. Bishop DiMarzio has strongly denied the allegation.

Since the original accusation in November 2019 — when DiMarzio conducted an apostolic visitation of the troubled Diocese of Buffalo — another accuser has come forward. DiMarzio has passed retirement age but remains in office.

If there is reasonable suspicion of guilt, mere sanity dictates that Bishop DiMarzio be removed and publicly tried. If the allegations are thin, that’s all the more reason to conduct a very thorough and very public investigation, with all possible speed. Neither the accusers nor the accused are served by the silent dragging of feet, and the faithful aren’t served by a lack of accountability.

There is no perfect justice this side of the Second Coming, but that’s no reason to let New York state’s efforts so far outstrip the Church’s to deliver a semblance of it here and now.

The problems with Church governance will not recede on their own. The maxim remains true, however: Sunlight is still the best disinfectant.

Christopher Altieri writes from Connecticut.