One of the most sacred cultural spaces in the United States can be found in my neighborhood, Treme’, in New Orleans. Treme’ is the oldest Black neighborhood in our country and is home to many significant Black contributions that have helped shape the cultural and social fabric of this country. Treme’ is where Venerable Mother Henriette Delille, foundress of the Sisters of the Holy Family, of which I am a proud associate member, is from. She is one of six on the road to canonization to become the first African American saints in the history of the Catholic Church. Treme’ is home to St. Augustine Catholic Church, which was built in 1841 by free people of color so that others, specifically the enslaved Africans of that era, could worship with some form of dignity despite the laws of the time. Treme’ was home to one of the initial sparks of the civil rights movement, Homer Plessy, a Black Catholic parishioner of St. Augustine Church.

Treme’ is also the birthplace of one of the United States’ most beloved cultural art forms: Jazz. It is the area where this art form was birthed that I would like to place our focus — Congo Square. Congo Square is a very sacred space in this country, especially to Black people. It is where, even to this day, people gather on Sundays to celebrate culture and pay homage to our ancestors. During the 18th century in New Orleans, enslaved Africans were commonly “allowed to be off” (I use this phrase with some reservation) on Sundays, as was detailed in the Code Noir , which regulated the lives of Black people — specifically the enslaved Africans — of the time. As the slave owners would gather in the French Quarter on Sundays, many of the enslaved Africans would gather in Congo Square nearby to celebrate their various cultures via song, dance, craftwork, etc. It was also during this time in Congo Square where they would interact with free Blacks and the Indigenous of the area, thus creating some of the food, music, celebrations and my own cultural traditions of the Black Masking/Mardi Gras Indians that much of the world enjoys today when they come to New Orleans. Despite the harsh conditions, it was during this narrow slot of time on Sunday afternoons that Black people were allowed to “breathe” — be our authentic selves in a society that did not welcome it, nor accept, as relevant.

I share this brief history about Congo Square as a sacred space because many people are in awe of these under-told stories when they visit New Orleans and realize the sacred history of the place where they are standing. Many of various backgrounds continue to be shocked at how little history they know about the city that they are visiting, or may even live in, and the contributions of Black people to the culture of the city — then and now. The same is true about the misunderstanding of the sacredness of Blackness in today’s society, specifically in our Church. Although, there are areas of teaching about our history and contributions, such the Institute for Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University of Louisiana , there has been very little taught about the Black contributions to our faith in our seminaries, higher education institutions, theology programs in Catholic schools, or even in religious education programs throughout our parishes. What continues to be taught is the “holiness/value” of “whiteness,” and the “dismissal/devaluing” of “blackness.” This continues to be seen in various Catholic resources that are published, programs that are aired, and conferences that occur. This sentiment causes many to feel that, if the Church does not value “blackness,” then why should society as a whole.

The questions I ask are these: Is our Church, like Congo Square, a safe and sacred place for people of color, specifically Black Catholics, to “breathe”? Can we express ourselves authentically and freely without being scrutinized, judged or criticized by other Catholics? Can the issues many of our communities face — such as economic injustice, racism, gentrification, mass incarceration, unequal resources, improper education, police brutality and many others — be deemed relevant pro-life issues in this country since they threaten the quality of life from the womb to the tomb for those in these communities?

Opening the eyes of others

It has been a year since the murder of George Floyd. Many world leaders, including Pope Francis, took notice of, and spoke about, this tragedy and its roots in America’s “original sin” of racism. Many white Catholic organizations held webinars and Zoom meetings — doing the best they could in the midst of restrictions caused by the pandemic — to address this issue. Many Black Catholics, and other Catholics of color, had to take on the unfair (but necessary in this moment) emotional burden to “educate” various Catholic entities about this “original sin” and how it is still present in our society and Church.

Because of this, many of us who are doing this work have received increased criticism, internet trolls, hate mail and messages by those who think that either we are attacking the Church or that racism is a myth. Many have been targeted as anti-Church or labeled as “troublemakers.” Many of us have had to educate and challenge mostly well-intentioned white colleagues who want to “do” something about their need to let go of control and let those affected by racism dictate what, how and when some things should be done. Many of us have had to challenge Church structure that any event, program or discussion should not center around making white people, or those in power or in places of privilege, comfortable, but to really advocate for those on the margins so that we can enact true measurable change and hear from, empower and give resources to those who are directly affected by the issue, thus challenging the “savior mentality” that sometimes those outside of the issue bring to addressing such issues.

This has been the painful path that many have had to take to fight this “original sin” for so many years, but it has been even more challenging this past year since the world witnessed the murder of George Floyd. Even one of his final statements, “I can’t breathe,” which was the same as many other unarmed Black folks who died at the hands of law enforcement in the past few years, has become a rallying cry for justice around the world.

I am part of an informal support group of young lay Black Catholic males involved in ministry around the country that was formed because we could not seem to find authentic support anywhere else in the Church. As you can guess, the numbers are low for this group that came together after George Floyd’s murder, mainly because there are so few of us who fit the category of young lay Black males in Catholic ministry. We have been trying to figure out how we can “breathe” — be our authentic Black Catholic selves in our own Church without being seen as “unholy” or a “threat.” We are exhausted about not being valued or seen by our own Church. We are tired of feeling unsafe in a Church where we are, at times, defending our involvement in the Church within our own community and fighting those who see us as a threat because we are advocating for our own community.

Finding hope and healing

Therefore, what can the Church, and those that want to be allies, do? Let the Church breathe! Let the Holy Spirit — the breath of God — flow throughout our Church and society to create hope and healing where it is needed.

We have found hope and healing breathing in those bishops and Church leaders who are open to understanding that saying the phrase “Black Lives Matter” is not an endorsement of an organization but the affirmation of a group of people that has been continually attacked and marginalized throughout the history of this country.

We have found hope and healing breathing in those Catholic spaces where we see white Catholics, and those in places of privilege and power, grappling with and trying to dismantle racism, white supremacy, biased thinking and other divisions within their parishes and organizations.

We see hope and healing breathing when our brothers and sisters of various races — most recently our Asian/Pacific Islander brothers and sisters who have experienced racist attacks since the pandemic started — finally accept our concerns as authentic problems that deserve attention and work with — not for, but with — our communities that have traditionally been ignored or left to fend for ourselves, to create effective and mutually beneficial relationships and change.

We have seen hope and healing breathe in spaces where we have seen dioceses taking a “racism inventory” of their structure and operations and are working to divert resources to make amends for past systemic racism that they may have participated in and perpetuated.

We have seen hope and healing breathe when we have seen our Church leadership working with local law enforcement to address the needed change — not to attack officers, but to address the broken justice system that has perpetuated the violence in so many communities of color that has gone unchecked.

Yes, there is still much work to do, and I believe much can be done in and through the Church. We have the documents, we have the road map of seeing each other “made in the image and likeness of God” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, No. 1934). Now we just have to humble ourselves, learn about and accept each other’s cultures, sacred spaces, values and traditions, and see our unique needs as equally valuable and holy as anyone else’s. It is then that we, as a Church, will be that sacred and safe space to allow the Holy Spirit to breathe life and healing in our, at times, suffocating body of faith.

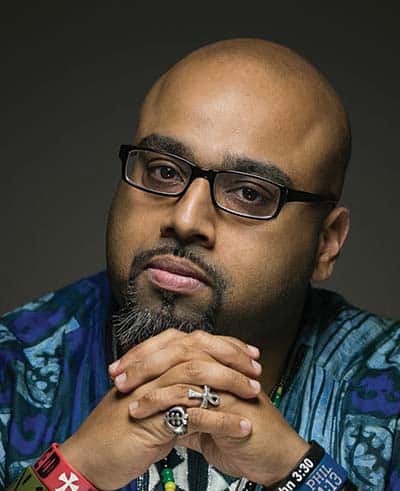

Ansel Augustine, D.Min, is the executive director of the Office of Cultural Diversity and Outreach for the Archdiocese of Washington.