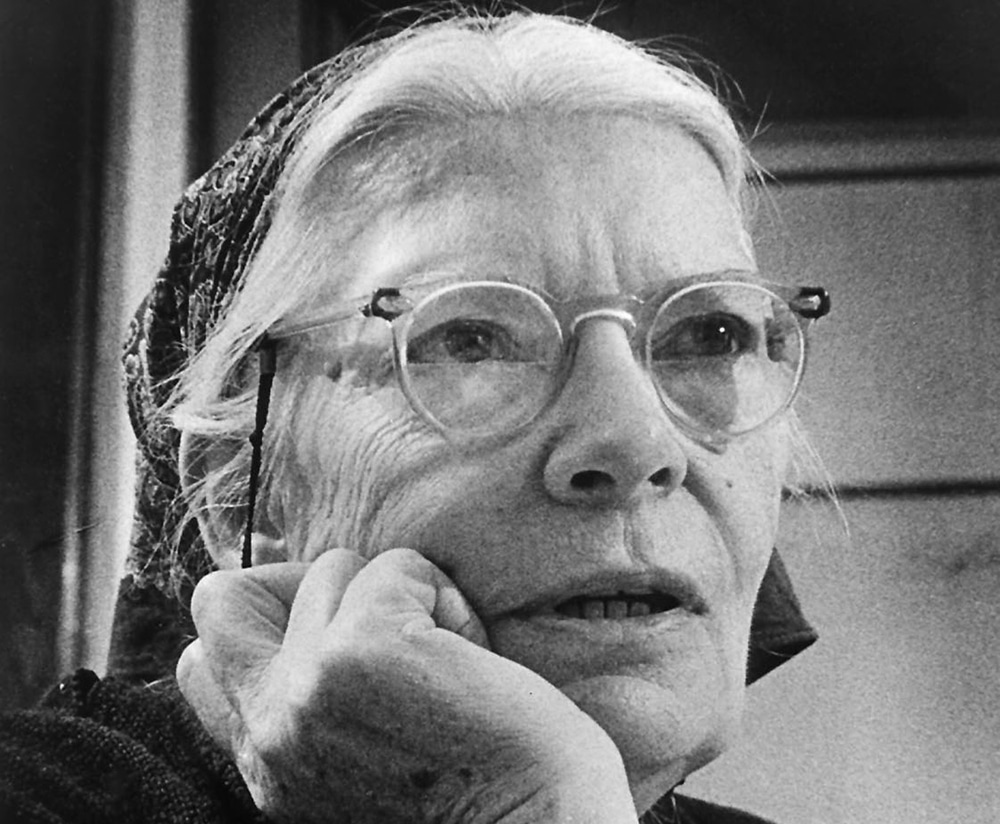

Sister Aloysia knew her by reputation, and that reputation wasn’t good. Dorothy Day was living with a man to whom she wasn’t married, who was even more left-wing than she was, and they had a baby, and they were living in the country among people who disapproved of everything they were and did.

“All the neighborhood knew that we and our friends were either Communist or Anarchist in sympathies,” Day wrote in “From Union Square to Rome.” “But those same dear Catholic neighbors who heard sermons excoriating ‘the fiendish and foul machinations of the Communists’ were kindly people who came to use our telephone and bring us a pie now and then, who played with us on the beach and offered us lifts to the village in their cars. Sister Aloysia, too, had no fear, only a neighborly interest in us all.”

Early motherhood forms an ideology-free zone. There’s that. It’s easy to be kind to someone who’s pushing a baby in a stroller. But the “we” to whom the neighbors were kind included her Communist and atheist common-law husband, who seems to have been publicly difficult about these things, and others like them. The neighbors crossed hard boundaries in their kindness.

Not everyone would do this. Day doesn’t say every neighbor was like that, or that the neighbors who were like that were always like that. But they were unexpectedly kind enough for her to notice, and remember. They simply treated these odd people as men and women loved by God, and did not identify them first by their politics or their morals, or even their manners.

Many people like that wouldn’t be kind to a commie mother and her baby or a fill-in-the-name-of-hated-ideology mother and her baby. A young friend has suffered being ostracized by the good Catholic women nearby for her poverty and her politics, and I know other stories of the same sort, just within Catholic circles, never mind secular and ideological circles. It’s what happens when politics becomes identity.

Day’s neighbors acted like neighbors and the sister like a friend, though they must have felt communism and anarchism to be the blackest evils, and strongly disapproved of people living in sin. We approve of their overlooking their political disagreements to be kind to this young woman with her baby and her difficult husband. We look back 100 years and admire their kindness, but being kind would not have been easy.

I’d like to think I would have been as kind as her neighbors even had I thought what they must have thought. It’s easy to relativize political differences from so long ago. But then I wonder how I’d act in the parallel situation, if some alt-rightists lived in a house in one of the five houses on our short street.

How would I talk to the young mother with swastikas tattooed on her arms when I ran into her pushing her baby in a stroller down the street? What if her boyfriend bragged about going to D.C. and invading the Capitol? What if he was wearing a “Camp Auschwitz” T-shirt? And came over to borrow the lawnmower?

I would feel about them the way Day’s neighbors felt about Communists. If not moreso. Alt-rightism is as dangerous a bad idea as communism. The bigotry, the hatefulness, the stupidity. The anti-semitism. The hatred of Christianity or the blasphemous misuse of Christianity, depending on the group. The simple-mindedness and the smugness. It pushes all my buttons.

What do you do? Love them as you can, obviously. But does that include bringing them pies, playing with them on the beach, giving them lifts? The saints would tell us to befriend them, remind us that no one is beyond the reach of God’s grace, that we could have been or may be in a different way such as them, that the only thing that will break their hard hearts will be love, that such depraved humanity can only be healed by their meeting the True Man in his people. Love may well include correction, but it begins with kindness.

They’d remind us of the conservative people who befriended the radical, unwed mother Dorothy Day. They’d remind us that those neighbors may have had some part in bringing her into the Church, by not being the bigots she seems to have expected. The world owes them great thanks.

In her autobiography “The Long Loneliness,” Day described her mentor Peter Maurin’s understanding of others: “He made you feel that you and all men had great and generous hearts with which to love God. If you once recognized this fact in yourself you would expect and find it in others.”

Maurin called this “the art of human contacts.” Day explained: “It was seeing Christ in others, loving the Christ you saw in others. Greater than this, it was having faith in the Christ in others without being able to see him. Blessed is he that believes without seeing.”

Dorothy Day’s kind neighbors seem to have seen Christ in her, her child, her abrasive, communist lover and their radical friends. I’m guessing they wouldn’t have put it like that. But they treated her with unexpected kindness, and the world benefited.

David Mills is the senior editor (U.S.) of the Catholic Herald. He writes from Pennsylvania,