GRINNELL, Kan. (CNS) — A first Communion class of one.

This seems unthinkable in some towns in Kansas, but in parts of the Salina Diocese, it is a reality.

“Our director of religious education begs year after year for catechists, but we barely have enough,” said Leona Dickman, a parishioner at Immaculate Conception Parish in Grinnell. “I stepped up to teach because I want my granddaughter to have a good Catholic background.”

She has worked as the parish secretary since 2014, as well as served as a catechist off and on for more than two decades. Most recently, she led the second- and third-grade class, which included two students, one of which was her granddaughter Taryn Dickman, the parish’s only first communicant this year.

With the trend of declining populations in rural Kansas, these dwindling numbers mean small sacramental classes and decreasing numbers in parish participation.

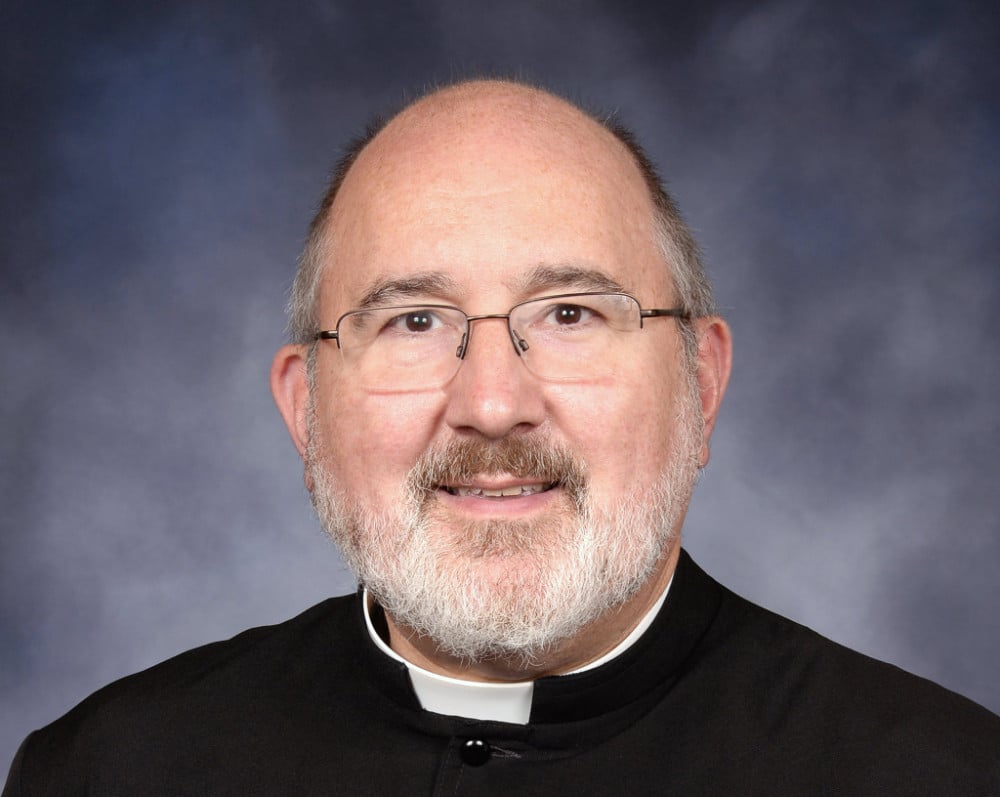

“This year, we have four first Communion students at Clifton and zero at Clyde,” said Father Steve Heina, pastor of St. Mary of the Assumption Parish in Clifton and St. John the Baptist Parish in Clyde. “Our religious education classes at Clyde generally have between five and 10 students, and we typically have a few less in Clifton.”

The parishes, which serve the population in a geographical area that spans portions of three counties, have a combined confirmation class comprised of 16 students.

In the central and eastern portions of Washington County, the parishes of St. Augustine in Washington and Sacred Heart in Greenleaf also combine their religious education classes. Father Joseph Kieffer, who is the pastor of both parishes as well as of St. John the Baptist parish in Hanover, said there are an average of eight to 10 students in each combined class, with larger confirmation classes due to the two-year preparation process.

While small sacramental classes have become the norm for these and other rural parishes, there are concerns that accompany those smaller numbers. For Father Heina, the quality of the interaction between the students themselves, and between the catechist and the students, is one such issue.

“With a small number of students in each class, it doesn’t generate a lot of discussion among the students,” Father Heina told The Register, Salina’s diocesan newspaper. “It takes a certain number — a minimum number — to have an energized discussion.”

Another challenge rural parishes face is finding volunteers willing to lead religious education classes.

“We’ve struggled trying to keep teachers and get teachers who want to teach the religious education classes,” Father Kieffer said.

The reasons for the scarcity of catechists are varied, Father Heina said.

“The two biggest obstacles I’m facing are the time commitment involved for catechists to prep and to teach, and the confidence in our potential catechists,” he said. “Sometimes they feel very inadequate in their ability to teach about religious matters. Informed catechists are important.”

He recognizes that continuing faith formation as an adult can be challenging but stresses that living the faith is vital.

“I think it’s part of the overloaded schedules and lives of people that (continued religious education) falls off their radar,” he said. “In all religious education — for children and adults — a good grasp of the subject matter is important, but what we’ve added in the past several years is the (importance of the) lived faith.

“So, it’s not just head knowledge or book knowledge or computer knowledge,” he added, but it’s considering “how do I apply this to my life — in my witness, my prayer life and social justice teachings of the church?”

The decreasing population in rural Kansas could be contributing to the trend of fewer catechists, smaller sacramental classes, and fewer religious education students.

The number of residents in Gove County, for example, decreased by 12% between 2000 and 2010, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Between the 2010 census and the 2018 Population and Housing Unit Estimate that the bureau compiled, the number decreased an additional 3%.

Coupled with a population decrease is a shift of religious belief, as well. According to the Pew Research Center’s 2019 report, the percentage of Catholics in the U.S. population dropped 3% from 2009 to 2019.

While the local impact of national trends can take time to be felt, the year-to-year needs and challenges in the Salina Diocese’s parishes are obvious and immediate.

Dickman says children need religious education, but the formation must start at home under the guidance of their parents. Then, even if there is only one student in a formal parish class, the sacraments need to be emphasized.

“Every soul is worth saving, and they need the sacraments to conduct themselves in the faith and stay Catholic in the future,” she said. “I’ve seen young kids go (to religious education classes) until they get confirmed and then they see it as having graduated, but it’s not. It’s supposed to be a lifelong education.”

Father Heina suggests that individuals across the diocese can play a part in encouraging, building and sustaining solid religious education programs to benefit children and adults alike.

“Financial support is always significant,” he said, “but I think when kids can see not only their parents but other adults in their parish growing in their faith — not just coming to Mass but how the faith helps these folks be better people — I think that’s the single most supportive thing parishioners can do.”