The Church depends upon the intercession of the saints. Devotions to the holy men and women abiding in heaven are part of the fabric of Catholic spirituality. And we do not only turn to the saints for help in time of need, but we also turn to their virtuous lives as inspiration in Christian living. Where the saints have gone, we hope to follow.

Scripture says, “Nothing is new under the sun” (Ecc 1:9), and there is great truth to that. The sufferings and difficulties posed by the current COVID-19 pandemic and resulting crisis in society have been faced by humanity at different times. But it’s also true that the threats we are facing are unique and demand from us an abundance of reason and faith.

As we consider the impact the current pandemic has leveraged on society and ecclesial life, it is helpful to turn to the saints. In them, we can find a model for reaching out, for shepherding God’s flock, and for continuing to strive for holiness during this time of crisis. The witness of these holy men and women is here to strengthen us as we face our present challenges. We have much to learn from them, and we pray that they intercede for us now and always.

St. Aloysius Gonzaga (June 21)

Born into a noble family, St. Aloysius Gonzaga (1568-91) gave up a privileged and comfortable aristocratic life in pursuit of service to the Church as a priest. He knew that a greater inheritance awaited him, saying “It is better to be a child of God than king of the whole world.”

Inspired by the stories of missionaries he read while suffering from a kidney ailment at an early age, Gonzaga desired to be a missionary himself. His desire to give his all in service to this ministry of the Church became somewhat hampered because of additional health complications. Nonetheless, Gonzaga’s call to give his all for Christ was realized in unimaginable ways.

Gonzaga’s own acquaintance with suffering opened his heart to love, since it conformed him more and more to Christ crucified. “He who wishes to love God does not truly love him if he has not an ardent and constant desire to suffer for his sake,” he said. As his health continued to weaken, Gonzaga received a vision from St. Gabriel the Archangel, in which he learned he would die within the year ahead.

In 1591, a plague struck Rome. Gonzaga responded to the needs of victims without hesitation, paying no mind to what it might cost for him. Eventually, his superiors kept him from ministry among the plague victims, considering his own precarious health and the infection of several of his confreres.

Later, Gonzaga returned to ministry among the sick, but in what was thought to be a hospital for those without infectious diseases. As it turned out, one of the patients Gonzaga assisted had the plague. Gonzaga came down with the disease and, after languishing for weeks, his health steadily deteriorated. The Jesuit scholastic Gonzaga lived what his spiritual father and confrere St. Robert Bellarmine taught: “The school of Christ is the school of love.”

Gonzaga died on June 21, 1591, with the name of Jesus on his lips. His great humility allowed him to see past his own difficulties and needs and respond in love to the needs of others — remembering that it is in others, especially the poor, where we encounter Christ himself.

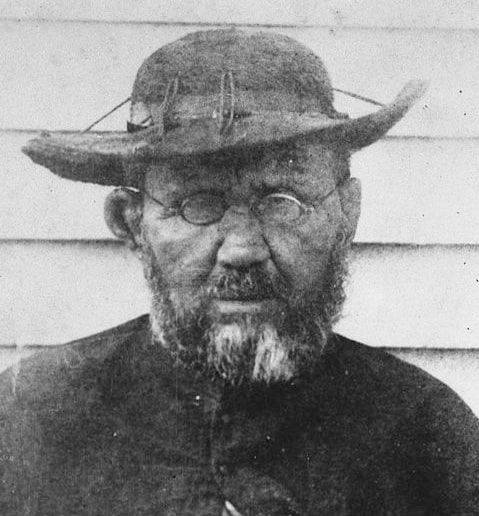

St. Damien of Molokai (May 10) and St. Marianne Cope (Jan. 23)

St. Damien De Veuster (1840-89) was born in Tremelo, Belgium, and entered the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary in 1859. Within a few years, Damien volunteered for Hawaiian missions, taking the place of his sickly priest-brother who could not make the trip. In God’s providence, his mission to Hawaii would provide the means by which Damien achieved sanctity — culminating in his canonization in 2009.

After arriving in Honolulu in 1864, Damien was ordained a priest. After nearly a decade of ministry among the flock entrusted to him, there was an outbreak of leprosy — the infectious disease that typically results in the gradual bodily decay of one fully alive. Victims of the disease were forced from their homes and into permanent quarantine on the island of Molokai. Not only were they never to see their families again, but they knew a slow, painful death awaited them.

Hawaiian Bishop Louis Maigret began looking for priests to minister among the lepers on Molokai, deciding to solicit volunteers since accepting the assignment essentially meant accepting a death sentence. Damien joyfully and heroically offered himself, and he left for Molokai on May 10, 1873. This mission, earning him the title “apostle to the lepers,” would eventually lead to his death from the disease.

Damien spent over a decade and a half in service to the lepers of Molokai, celebrating the sacraments and giving structure to a community. He even built housing facilities and bandaged wounds. The lepers didn’t just suffer physically. Totally shut off from the world, awaiting death, the lepers in his care were mostly hopeless. The lepers on Molokai often gave into lewd and sinful behavior, but Damien challenged them to be better.

Damien’s primary role was to lead the lepers closer to Christ, and that required giving them hope. In what could be an easily overlooked aspect of his work on Molokai, Damien gave a hopeful new perspective to the “living dead” by digging graves so the dead of Molokai would have a dignified burial. Damien showed the lepers that their bodies deserved dignity, even in death. Their suffering was transformed to have purpose, and this led them along the path of hope in eternal life. By the time Damien died, the majority of the island was Catholic.

In 1888, Damien was joined in his ministry to Molokai by St. Marianne Cope (1838-1918) and other Sisters of St. Francis from Syracuse, New York. The former hospital administrator led a group of sisters to Hawaii a few years earlier, after nearly 50 religious orders refused Hawaiian King Kalakaua’s invitation to care for the victims of leprosy in his kingdom. Eventually canonized herself, Cope cared for Damien when he became a victim of leprosy.

Damien died at age 49 on April 15, 1889, already an internationally acclaimed humanitarian. Originally buried under the tree where he slept his first nights on Molokai, his remains were moved to his homeland in 1936 at the request of the Belgian king. Cope carried on his work there and died at 80 on Aug. 9, 1918.

Both St. Damien and St. Marianne teach us that our truest joy and fulfillment is to be found in obedience to God’s call. Inspiring us by their fortitude and charity, these saints teach us to reach out to the ill and those affected most severely by our current social distancing.

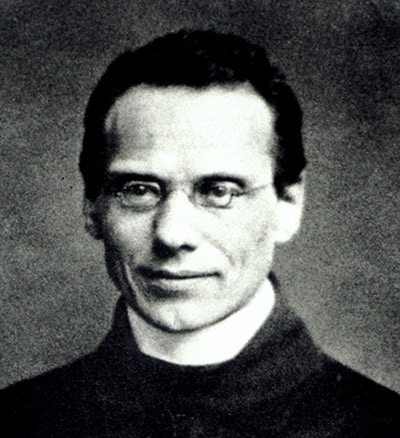

Blessed Francis Xavier Seelos (Oct. 5)

Blessed Francis Xavier Seelos (1819-67) spent his life leading many souls to the Lord through preaching and the sacraments. By his own witness and intercession, as well as his inspiration to priests today, Pope St. John Paul II noted at Seelos’ 2000 beatification, “Today, Blessed Francis Xavier Seelos invites the members of the Church to deepen their union with Christ in the Sacraments of Penance and the Eucharist.”

An immigrant from Germany, Seelos was drawn to ministry as a Redemptorist, the religious congregation founded by St. Alphonsus Liguori known for works of evangelization and care for the poor. He set out to join the congregation’s mission in America and was ordained in Baltimore in 1844. After parochial assignments in Pittsburgh and throughout Maryland, Seelos took up formation work for the Redemptorists.

Cheerful and kind, Seelos always was smiling. He enjoyed a good joke and wasn’t afraid of humor. Devotion to prayer and dependence on the will of God also characterized Seelos. Quickly developing a reputation as an ideal pastor, Seelos was known for his empathy and understanding as a very popular spiritual director and confessor. His confessional became known as a place of forgiveness and mercy, open to all who wanted divine healing. “I hear confessions in German, English, French, of whites and of blacks,” Seelos said.

From 1863 to 1866, Seelos was a travelling missionary who preached in English and German throughout many states between Rhode Island and Missouri. After a few months at a Detroit parish, Seelos arrived as pastor of Assumption Church in New Orleans in 1866. Prophetically, he stated, “I have come here to pass the rest of my days and find a last resting place.”

In New Orleans, Seelos was known for his devoted service to the poor and marginalized. Caring for the victims of an outbreak of yellow fever, Seelos contracted the disease himself. Suffering intensely but patiently, Seelos died on Oct. 4, 1867, at the age of 48.

Seelos is a model for our priests and bishops, showing the importance of continuing sacramental ministry even amid contagious outbreak. Without minimizing Seelos’ noble humility and sacrificial character, his death shows the dangers of ministry on the frontlines in situations such as what clergy are currently facing — which means leaders should develop systems to both provide the sacraments and protect the health and safety of the ministers.

St. Charles Borromeo (Nov. 4)

Although appointed to high office in the Church early in his life (thanks to nepotism), St. Charles Borromeo (1538-84) rose above a great deal of corruption in the Church on account of his personal holiness. His uncle, the pope, brought Borromeo into the service of the Holy See. He took on a variety of notable appointments and was made a cardinal at quite a young age. Through these high offices, Borromeo worked to bring a host of reforms to the Church.

Although not ordained a bishop, Borromeo was given administration of the archdiocese of Milan, which he managed from Rome for quite some time. After completing his assistance with the Council of Trent, Borromeo was able to take up residence in Milan at last. He led a simple life there and generously shared the sizable income he earned. But people were very loose in their practice of the Faith. Mass attendance was low, clergy were unmotivated and uneducated, and corruption and immorality were widespread. Borromeo reformed his local Church: He established provincial councils, renewed the clergy through instituting better seminaries and worked to instruct the laity in doctrine. Some of his reforms were met with strong opposition, and there was even an attempt on his life.

When plagues struck Milan, Borromeo’s pastoral approach was defined by faith and reason. At times he put his life on the line to minister to his flock. He also attended to the common good by closing up churches. He insisted outdoor Masses be celebrated so that the faithful could participate through their windows. (Milan was then a tenth of its current size and people rarely received holy Communion at that time.) His legacy lives on in the pastoral ingenuity that has sparked live streamed Masses amid the suspension of public worship, providing an opportunity for the faithful to further realize their mystical participation in Masses even when not present. Borromeo also personally oversaw recovery efforts and ministered to the dying, buried the dead and absorbed large debts to alleviate the suffering. On his way home from a retreat in 1584, Borromeo fell ill and died when he was only 46 years old.

St. Roch (Aug. 16)

Most of what we know about St. Roch is attributed to legend, as there is no historical record of his life. The power of his witness and miraculous intercession in times of plague have been manifest by devotion of the faithful over the course of centuries.

Said to have been born in the 14th century after his barren mother prayed for the Blessed Virgin Mary’s assistance, Roch was set aside as special from the beginning. Such was symbolized on his chest, where he bore a red cross on his skin since birth. He was known from earliest years for his piety and austerity.

Called by God to renounce his family’s wealth after his parents died, Roch gave up the office his father established for him near their home in southern France. Instead, he set out into Italy as a poor beggar, in the mendicant style of St. Francis of Assisi. At the time Italy was being ravaged by a plague, and Roch spent himself in service to the sick and dying, particularly through a ministry of healing. Many were recipients of miracles attributed to his prayers or touch. And in each place he visited, the plague went away.

Eventually Roch himself became ill and was thrown out of town. After taking up shelter in a forest, Roch built a hut. Nearby, a miraculous spring arose, and a wealthy man’s dog brought him bread and healed him by licking his wounds. Returning home in disguise, he was thought to be a spy. Falsely accused, and choosing to be silent before his accusers in imitation of Christ, Roch was arrested and put in jail. Never revealing his true identity out of a disdain for worldly glory and comfort, Roch died there after five years.

Roch’s own imprisonment kept him from the sacraments. According to legend, as he spent his time looking out the jail cell window, a guard once asked what he was always staring toward. “I am looking at the tower of the parish church,” he replied. He knew where Christ was, and he joined himself to Christ in his heart. This can relate to our own present circumstances or social distancing and quarantine, unable to join in public worship or, perhaps, even make visits in our churches.

Revered as a patron against plagues and pestilence, particularly invoked during medieval times, St. Roch has been credited with interceding to end epidemics in many places over the centuries since his death.

St. Frances of Rome (March 9)

Born into a wealthy family, St. Frances of Rome (1384-1440) was forced into an arranged marriage at 12 years of age. Her military commander husband was frequently away at war, which helped contribute to the success of the four decades’ long union between them. But Frances’ husband also admired his wife, and there was a great deal to admire. Once when she was sick early in their marriage, Francis’ husband summoned a magic man, who Frances threw out of the house. She lived her faith heroically, seen especially in her noteworthy care for the poor and sick throughout Rome.

The times in which Frances lived were marked by wars, divisions and disasters. When times of disaster struck, she committed large portions of family resources to assisting the poor and the sick, even turning their country estate into a makeshift hospital. The storage units of the family estate miraculously would be replenished on account of Frances’ prayers.

Those suffering the loss of loved ones due to the current pandemic can find in Frances a special friend. When a plague struck Rome, Frances lost two children to the disease. Rome was particularly chaotic at the time because of the problems that ensued from various men claiming to be the pope. Making her home a hospital again, Frances also went out to the countryside collecting herbs for medicinal use. Many claimed that they were healed by God through her.

Frances founded two communities of women — one of active life that attended to the needs of society, and a monastic community. After caring for her husband in his final years, Frances moved into the latter, where she spent the last years of her life and served as superior. St. Frances of Rome died on March 9, 1440.

St. Rosalia (Sept. 4)

Not much is known about St. Rosalia (1130-66). Born into a noble family, she retreated into the life of a hermit as a young girl. Tradition has it that two angels led her to a cave outside of Palermo, Italy, where she took up residence for the rest of her life. There she took up a solitary life of prayer and penance. In the midst of a plague that struck Palermo in 1624, St. Rosalie appeared to a sick woman. A while later she appeared to a hunter near the cave where she lived, instructing him to locate her relics and carry them around Palermo after her death. After processing around the city three times, the plague ceased, and her relics were enshrined in the Palermo cathedral. For that reason, Palermo regards her as a special patroness. She became a frequent subject in Renaissance and Baroque art, invoked throughout Italy at times of plague. Her feast is popular among Sicilians and is marked with great celebration.

Michael R. Heinlein is editor of OSV’s Simply Catholic. He writes from Indiana.