This interest arises as people wonder about the process of presidential impeachment, rare in American history.

Beyond this question, Andrew Johnson should have a place in Catholic history books. When Catholics in this country needed a friend in high places, Andrew Johnson was there, forthright, unwavering and bold, risking political disadvantage for himself. He attended Mass regularly. His children and grandchildren became Catholics.

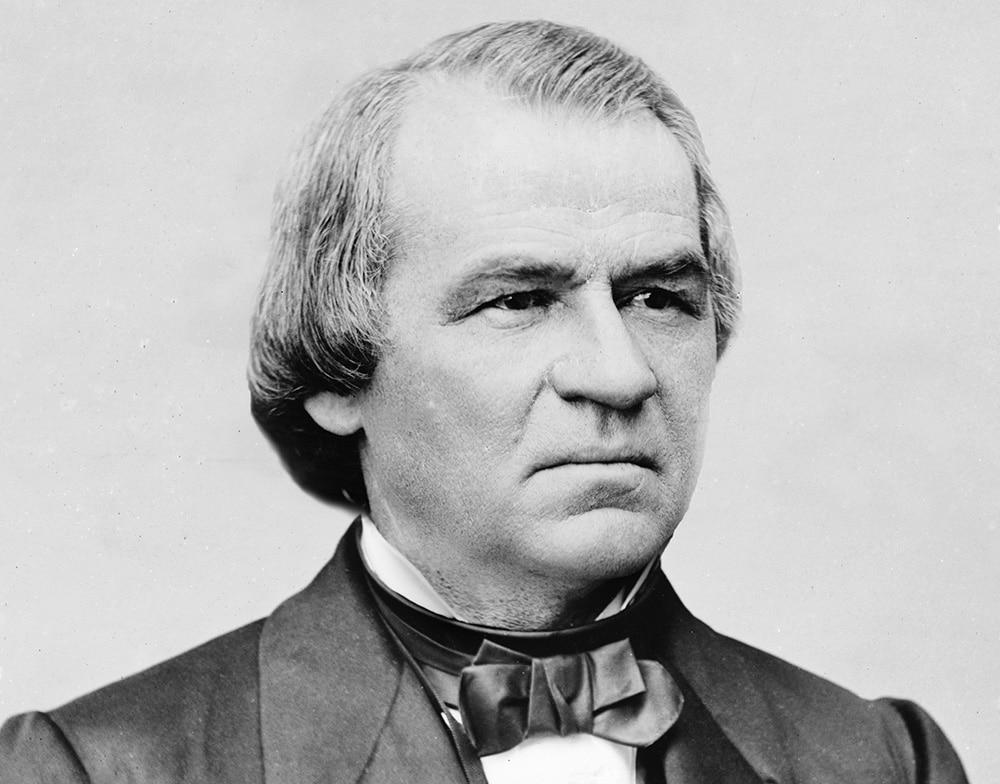

Johnson was born in Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1808. Reared in deep poverty, he never attended school.

In his adolescence, he moved, or fled, to Greeneville, Tennessee, one of the earliest communities of Americans west of the Appalachian mountain chain. In Greeneville, he became an apprentice to a tailor, and he also met a young woman from “the right side of town,” Eliza McArdle.

They were married. She had been properly schooled. While her husband sewed in his little tailor shop, still standing and a historic shrine, she taught him to read and write. She was a Presbyterian but open-minded.

Making friends, despite his rough edges, Johnson quickly climbed the political ladder, being elected mayor of Greeneville, and then he went to Congress.

At the time, Catholics, outside Louisiana and a few other places, were few, powerless and poor in America, most often immigrants from Europe or children of immigrants from Europe. As a rule, they were unwanted. Inevitably, they had a hard time. Think of many immigrants today to get the picture.

Now, it is impossible to imagine how threatened Catholics were at that time. Johnson championed Catholics. His first speech on the floor of the House of Representatives denounced anti-Catholicism.

After two terms in Congress, Johnson returned to Greeneville to run for governor of Tennessee. In the campaign, he blistered his opponent for voicing anti-Catholic views. Johnson was elected.

In 1857, he was sent to the United States Senate. The citizens of Tennessee voted overwhelmingly to secede from the Union and join the Confederacy in 1861, but Johnson, although a slave-owner and supporter of slavery, refused to accept the vote.

Abraham Lincoln thought that Johnson, a Southerner, who endorsed slavery but was loyal to the Union, was the ideal running mate in 1860. The Lincoln-Johnson ticket won, so, as vice president when Lincoln was killed in 1865, Johnson became president.

Rumors circulated that Lincoln’s death resulted from a Catholic plot to put Johnson in the presidency, abetted by the fact that several conspirators in the assassination were Catholics: Mary Surratt and her son, Dr. Samuel Mudd, and, it was alleged, even John Wilkes Booth himself. The pope and the Jesuits at Georgetown were accused of organizing the scheme.

Behind this elaborate, orchestrated Catholic foul play, it was said, was Johnson’s friendliness to the Church. With him as president, Catholics would enjoy favor and even run the country.

These charges were ridiculous, but they showed how well-known was Johnson’s regard for the Catholic Church, and they also demonstrated the fever of anti-Catholicism at the time.

Despite these whispers, Johnson’s fondness for the Church never stalled. He attended Mass every Sunday in a church in Washington. He and Eliza sent their sons to study under the Jesuits at Georgetown, their daughters to the Visitation nuns’ school.

Johnson’s presidency was controversial, so he was impeached but acquitted. After leaving office, he returned to Greeneville, where he was a generous donor to its little Catholic church.

He was visiting his daughter, who had converted to the Church, in 1875, in her home near Elizabethton, Tennessee. Suddenly stricken, it is thought with a stroke, he died. Unproven legend is that on his deathbed, his daughter baptized him a Catholic. No written record, only hearsay, exists, but it is not far-fetched.

Owen F. Campion is OSV’s chaplain.