In the coming liturgical year, the Church reads primarily from the Gospel of Matthew. The primary context for hearing the word of God is in the liturgy. To prepare ourselves to better receive what is given to us in our communal celebration, Our Sunday Visitor will offer a series of 12 In Focuses dedicated to exploring some central themes and texts in the Gospel of Matthew. We hope you will take up the task of “Meeting Christ in Matthew” as we address topics such as treasure in heaven, the promise to St. Peter, the parables, the prediction of the world’s end, the Sermon on the Mount, and others.

| 5 QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER |

|---|

|

Significance of structure

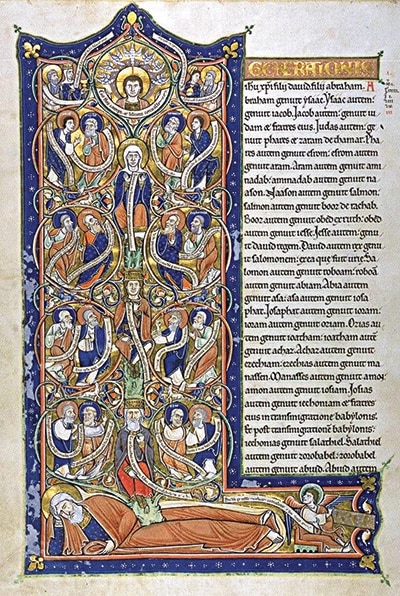

“When the fullness of time had come,” writes St. Paul, “God sent his Son, born of woman, born under the law” (Gal 4:4). The Incarnation takes place in the womb of a Jewess, the Blessed Virgin Mary, and it incorporates the Son into the life and history of the Jewish people. If the work of Jesus brings salvation to the whole human family, it does so first by bringing to perfection the life of God’s elect, the family of Israel. The Gospel of Matthew, with which the New Testament begins, situates Jesus within the wide sweep of Israel’s history. Jesus is not only “born of a woman, born under the law.” He is “Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham” (Mt 1:1). The work of God that began with Israel’s forefather in faith reaches its climax in the generation of “Joseph, the husband of Mary. Of her was born Jesus who is called the Messiah” (Mt 1:16).

Matthew signals this historical progress in the structure of the genealogy in Chapter 1. Unlike similar texts in the Old Testament, this list of ancestors does not move from some great figure on down: “This is the record of the descendants of Adam” (Gn 5:1); “These are the descendants of Shem” (Gn 11:10). Rather, the list moves toward Jesus, and the symmetry with which it does so identifies him not simply as the next in line but as a figure who marks a new epoch in history. “Thus the total number of generations from Abraham to David is fourteen generations; from David to the Babylonian exile, fourteen generations; from the Babylonian exile to the Messiah, fourteen generations” (Mt 1:17).

The pattern alone is sufficient to convey the significance of Jesus. We might, though, discern additional meaning in the number of generations. Letters in the Hebrew alphabet possess numerical value, and the letters of David’s name (dalet, waw, dalet) add up to 14 (4+6+4). This echoes at least half of Matthew’s emphasis on Jesus as “the son of David, the son of Abraham” (Mt 1:1). The number might also be significant as the double of seven. The three periods of 14 amount to six groups of seven and might be taken to place Jesus at the head of a seventh — a sort of genealogical Sabbath. This has merit, but it may not be what makes the most sense of the text. After all, Jesus begets no one, and the related theme of becoming “children of God” is not one as present in Matthew as it is elsewhere (cf. Jn 1:12-13).

A related suggestion is more plausible in my view. In a homily on the Book of Numbers, the third-century theologian Origen draws an analogy between the 42 encampments made by Israel on its journey toward the Promised Land (cf. Num 33) and the 42 generations (3×14) that lead to Christ. Given the analogy between entrance into the Promised Land and entry into Christ’s rest made by the Letter to the Hebrews, there is more to Origen’s suggestion than first appears. And given that this entrance is spoken of as an entrance into rest (cf. Heb 4:1), there might yet be something to the idea that the genealogy leads toward a sabbath of sorts.

In the line of David

As for the substance of what it means for Jesus to finish the long march of Israel’s history, Matthew directs our attention to the titles “Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham.” The last of these concerns the covenant promises given at the moment of Israel’s origin. “The Lord said to Abram: Go forth from your land, your relatives, and from your father’s house to a land that I will show you. I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you; I will make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you and curse those who curse you. All the families of the earth will find blessing in you” (Gn 12:1-3). The first elements of this, the gifts of land and descendants, serve the third — namely, the service of Israel as a blessing to the nations. As seen already in Abraham, the vocation of Israel is universal in scope, and in Jesus it finds its realization.

The promise to David specifies (in part) the way in which this blessing is given. Through the prophet Nathan, David is told, “Your house and your kingdom are firm forever before me; your throne shall be firmly established forever” (2 Sm 7:16). Jesus, the son of David, son of Abraham, is the “king of the Jews” (Mt 27:37) through whom all nations will be blessed (cf. Mt 28:19).

This is all well and good, but we might doubt whether the genealogy succeeds in speaking of Jesus at all. Does it not, after all, culminate in the person of Joseph? Whereas the usual formula “X is the father of Y” applies in every other instance in the chapter, it cannot be said of Joseph’s relation to Jesus. Accounts of miraculous births are present in Scripture. By his grace, God overcomes the barrenness of Sarah (cf. Gn 21:1-3), Rebekah (Gn 25:21) and Hannah (1 Sm 1). Mary’s conception is analogous to these. In the Gospel of Luke, we even hear an echo of Hannah’s song (cf. 1 Sam 2:1-10) in Mary’s Magnificat (Lk 1:46-55). Even so, the conception of Christ is unique, for Joseph does not play the role played by Abraham, Isaac or the unnamed father of Samuel. He is not the biological father, since “before they lived together, [Mary] was found with child through the holy Spirit” (Mt 1:18). A genealogy that culminates in Joseph seems beside the point.

Some ancient authors reckon with this apparent difficulty. The Protoevangelium of James as well St. Ignatius of Antioch and St. Justin Martyr speak of Mary as belonging to the house of David. This may be true, but whatever the merit of this suggestion, the idea is not found in Matthew. It also aims to solve a problem that, in truth, is not there, for in Israel, legal and not natural/biological descent held the greatest weight. Jesus’ genealogy rightly runs through Joseph.

We see an example of this in the practice of levirate marriage (cf. Dt 25:5-10). According to this provision of the Mosaic Law, the brother of a deceased man was to father a child with his widow, and the child was to be reckoned as the child of the deceased. No such situation is in play with Joseph and Mary, but the principle holds. That both Matthew and Luke can run their genealogy through Joseph without so much as a comment affirms this. Indeed, Matthew wishes to foreground the fact that Joseph is not the biological father so as to introduce the question that the following verses answer: What is the origin of this child? Yes, he is by all legal means truly “the son of David, the son of Abraham,” but from where does he come?

From the womb of a virgin

In subtle but important ways, the genealogy prepares us for an answer. Readers have long noticed the presence of four women in the genealogy: Tamar, Rahab, Ruth and Bathsheba. Because the family tree runs from father to son, Matthew’s decision to mention these women is purposeful. One suggestion takes note of their identity as foreigners. Rahab was a Canaanite, as perhaps was Tamar. Ruth was a Moabite. Bathsheba was the husband of Uriah the Hittite, and so perhaps a Hittite herself. If this is the connection the Gospel wishes us to make, the inclusion of these women in the genealogy would affirm the role of the Gentiles in Israel’s past and defend their ever-greater presence in the new “Israel of God” (Gal 6:16) — namely, the Church. This would have been a welcome point of emphasis for the Church as a whole and more particularly for the mixed Gentile/Jewish community out of which the Gospel of Matthew grew in Syria.

Another suggestion speaks more directly to the concerns of the first chapter. The genealogy is not, as the great biblical scholar Raymond Brown observed, “a record of man’s biological productivity but a demonstration of God’s providence.” By its inclusion of “idolaters, murderers, incompetents, power-seekers, and harem wastrels,” the chapter gives clear witness to the character of God’s self-emptying love. (In this, Brown says, “It contains the essential theology of the Old and New Testaments.” I believe he is correct.) Even when the actors possess great fidelity, the outworking of God’s providence does not refrain from what can give rise to misunderstanding and scandal. Consider the women: When Judah, the father of her late husband, denies Tamar another son in marriage, she seduces Judah himself so as produce an heir; though Rahab is one of the Canaanites whom the Israelites are commanded to destroy, she helps Israel to enter the Promised Land and becomes herself the father of Boaz; Ruth, from the stock of Israel’s ancient enemy Moab, for the love of her mother-in-law Naomi, joins herself to Israel’s God and becomes the great grandmother of King David through her marriage to Boaz; and Bathsheba, David’s ill-gotten wife through the murder of Uriah, bears him the heir to his throne, Solomon.

The events surrounding the birth of Jesus are similarly eye-catching. The suggestion, taken up by Celsus in the second century and repeated down the ages, that Jesus was begotten by Mary’s infidelity is taken up by Joseph as well. Not without reason does he intend “to divorce her quietly” (Mt 1:19). Mary is no foreigner, as are the women above, but as one apparently guilty of adultery, she, too, would have fallen outside the good graces of the Law. And yet Matthew reveals her, like the women before her, to be the unlikely instrument of God’s providence. If in the other cases it was true that, as Raymond Brown writes, “God had overcome the moral or biological irregularity of the human parents … here he overcomes the total absence of the father’s begetting.” Tamar, Rahab, Ruth and Bathsheba all anticipate the definitive work to be brought about in the Blessed Virgin. Their presence in the genealogy prepares us for the radical divine intervention that God begins in Mary. This child, who by law is “the son of David, the son of Abraham” is also brought forth “through the Holy Spirit” (Mt 1:18, 20).

In preparing his readers to understand the coming of Christ, Matthew turns also to the words of Isaiah. The Virgin Mary not only bears a likeness to those whom God has raised up before in Israel, but she is also anticipated by the prophets. The virginal conception of Jesus through the agency of the Holy Spirit “took place to fulfill what the Lord had spoken by the prophet: ‘Behold, a virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and his name shall be called Emmanuel'” (1:22).

An Old Testament parallel

It is commonplace to view Matthew’s citation of the Old Testament as daft. Any careful reader will see that Isaiah’s Emmanuel prophecy most certainly addresses the political happenings of Israel in the days of King Ahaz. Therefore, the passage does not — as the argument runs — concern what came to pass more than seven centuries later. Rather, it aims to hear the prophetic word on its own terms. Not every utterance of the prophets is an act of long-distance future-telling. It’s fair to argue that the promise of Emmanuel is fulfilled with the birth of Ahaz’s son, Hezekiah. In the theology of the Book of Isaiah, Ahaz and his son function respectively as images of infidelity and fidelity. While his father is rebuked, Hezekiah shows, in Moses-like fashion, the type of obedience that in time will lead to Israel’s return from exile. For the Book of Isaiah, therefore, Hezekiah is both an individual historical person and also a mold in which future leaders are to be cast; so, too, the “office” of Emmanuel. It is occupied by Hezekiah, and it awaits a future and fuller instantiation, such as is suggested by the cosmic descriptions of the child in Isaiah 9:5 — “Wonder-Counselor, God-Hero, Father-Forever, Prince of Peace.”

God’s providence is replete with what Robert Alter calls “duplicating patterns.” Hezekiah is the first Emmanuel; the Book of Isaiah does not anticipate that he is the last. (To insist with the critics of Matthew that the prophetic word admits of one and only one fulfillment is a constraint on the word of God in ways that it does not wish to be constrained.) Matthew’s citation, far from being daft, capitalizes on this openness of the prophecy. That, moreover, Isaiah 7:14 (NIV) should speak of Emmanuel as being conceived by a “virgin” (parthenos in the early Greek translation of the Old Testament) only strengthened the identification. So too did the meaning of “Emmanuel” as “God-with-us.” Unlike the first Emmanuel, the king Hezekiah, Matthew recognized in Jesus one truly born of a virgin, one who truly is a sacrament of God’s presence, and one who truly will “save his people from their sins” (Mt 1:21). Matthew’s citation of Isaiah is well-considered and true. And it demonstrates for us the identity of Jesus not only as David’s son and Abraham’s, but also God’s.

Jesus as the new Moses

This grafting of Christ onto the history and hope of Israel comes to the fore with Jesus’ birth and sojourn in Egypt. The Exodus was remembered as God’s foremost act of deliverance. As such, it served as the template of God’s future and final liberation. So it was, for instance, that in the time of the Babylonian exile, the prophecy we hear in Isaiah speaks of the coming deliverance in terms reminiscent of Exodus. God, for example, “opens a way in the sea” (Is 43:16) and extinguishes “chariot and horse” (Ex 14-15). So, too, he draws “water from the rock” (Is 48:21; Ex 17:1-7). And in time he will establish “Zion” (that is, Jerusalem) as a new Mount Sinai from which “shall go forth instruction, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem” (Is 2:3).

| 3 KEY LESSONS |

|---|

|

This anticipation of a new and final Exodus echoes in the mouth of John the Baptist. On the cusp of Jesus’ public ministry, we hear John proclaim the words of Isaiah: “A voice of one crying out in the desert, ‘Prepare the way of the Lord, make straight his paths'” (Mt 3:3; cf. Is 40:3). This connection between Jesus and the new Exodus appears already in the preceding chapter. After relating the genealogy, conception and birth of Jesus at the opening of his Gospel, Matthew tells of Jesus’ sojourn in Egypt in the second chapter. The affinities between Our Lord’s own biography and that of Moses are striking. As Pharaoh sought to kill Moses (cf. Ex 2:15), so Herod seeks the life of Jesus (Mt 2:13-14). And just as the king of Egypt massacres the Hebrew children (Ex 1:22), so king Herod commands the slaughter of the innocents (Mt 2:16). After the death of Pharaoh, Moses is told in a dream to return to Egypt (Ex 4:19). So also after the death of Herod, St. Joseph is told in a dream to return to the land of Israel (Mt 2:19-20). And just as the return of Moses sets in motion the great events of the Exodus wherein the Lord draws Israel through the waters of the Red Sea, so the return of Jesus at the end of Matthew 2 opens onto John’s cry to “prepare the way of the Lord” and Jesus’ descent into the waters of the Jordan. There follows both a period of trial in the wilderness (Mt 4:1-11) and the giving of a new Law (Mt 5-7). The meaning could hardly be clearer.

Already in his childhood, Jesus begins to recapitulate the whole history of his people. In these short opening chapters, Matthew reveals the central components of Christ’s identity that will occupy his writing in the remainder of the Gospel. Jesus is the “Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham.” He is the true Emmanuel foreseen by Isaiah, who like Moses will lead Israel in a new exodus from death to life.

Anthony Pagliarini is an assistant teaching professor and director of undergraduate studies in the Department of Theology at the University of Notre Dame.

| COMING NEXT MONTH |

|---|

|

In January, we will explore Matthew’s use of Old Testament passages. In what way does the evangelist read and understand the Scriptures of Israel? What do the passages cited teach us about Jesus? How does Matthew’s manner of reading the Old Testament shape our own?

|