The last line in Venerable Henriette Delille’s obituary from 1862 sums up her vocation.

Henriette Delille, the obituary reads, “for the love of Jesus Christ made herself the humble devout servant of slaves.”

“In the eyes of the world, Venerable Henriette may not have accomplished much, but in the eyes of God, she did very much,” said Sister Doris Goudeaux, a Sister of the Holy Family and the co-director of the Sisters’ Henriette Delille Commission Office.

Sister Doris is assisting with the canonization cause of Venerable Henriette Delille, who in 1842 founded the Sisters of the Holy Family, a congregation for black women religious headquartered in New Orleans.

Venerable Henriette Delille — who was born a free woman of color in 1812 — and her sisters helped the poor, cared for the sick and instructed the ignorant — free and enslaved, children and adults. They educated slaves in pre-Civil War New Orleans when that was prohibited by law.

“They had to be careful and do some things in secret,” Sister Doris said. “When they were teaching, they would have classes for free people of color in the daytime, and in the evening they would teach the slaves. They would do the same thing for classes in religion.”

Delille and her sisters cared for the sick and dying during a yellow fever epidemic that struck New Orleans in 1853. They arranged homes for orphans and took in elderly women, opening one of the country’s first Catholic nursing homes.

“We think she’s a saint. It’s up to the Church now to affirm that,” said Sister of the Holy Family Sylvia Thibodeaux.

“She lived faith, hope and love heroically, and she left that legacy for us to follow,” Sister Sylvia told Our Sunday Visitor. “We’ve tried for over 175 years to carry out that mission by responding to the needs of our time, in the best way we could, and she has served as an intercessor for so many of us.

“We call on her in our time of need,” Sister Sylvia said.

Journey to beatification

Henriette Delille’s cause for sainthood was opened by Archbishop Philip Hannan of New Orleans in 1988 and unanimously endorsed by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops in 1997. Pope Benedict XVI declared her “venerable” on March 27, 2010.

A possible miracle that would have cleared the way for her beatification stalled in 2005 when the Vatican’s Congregation for the Causes of Saints failed to reach a definitive conclusion about whether her intercession had lead to the miraculous healing of a 5-year-old.

Nearly 15 years later, another alleged miracle — the unexpected healing of 19-year-old Arkansas college student Christine McGee from an aneurysm — has the Sisters of the Holy Family hopeful that their foundress may soon joined the ranks of the “blessed.”

“The student was very sick, and the doctor said she probably wouldn’t make it, but her mother is very devoted to Henriette Delille,” said Sister Doris, who added that McGee’s mother later wrote to the sisters to inform them that she had prayed for her daughter’s recovery through Venerable Henriette’s intercession. She had family members also seek out her intercession.

“The mother told us that she called (Christine) her walking miracle,” Sister Doris said.

The Diocese of Little Rock, Arkansas, gathered evidence and submitted documentation on the alleged miracle to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints, which last December issued a decree certifying that the inquiry was done correctly and that the case could continue.

“We’re hoping it’s accepted as a miracle,” said Sister Doris, who added that the beatification Mass would be held in New Orleans.

“It would be much bigger than Mardis Gras,” she said.

| Sainthood cause of Venerable Henriette Delille |

|---|

|

Venerable Henriette Delille is the first U.S. native born African American woman whose cause for canonization has been opened by the Catholic Church.

|

Antebellum New Orleans

The New Orleans that Henriette Delille was born into more than two centuries ago was much different than the modern beloved city of jazz, Bourbon Street and the French Quarter.

Free women of color in antebellum New Orleans had limited life choices. Many of them, in essence, became long-term concubines with white European men. Venerable Henriette Delille’s mother was a descendant of her slave ancestor from West Africa. Her father was French.

“Venerable Henriette’s whole background has slavery in it,” Sister Doris said. “Henriette’s mother may have been the first in the family to be born free before her.”

There is some evidence that a teenage Henriette Delille may have had a similar relationship with a white European man of means. In recent archival discoveries, diocesan workers located funeral records for two young boys identified as the sons of Henriette Delille.

“We didn’t find this out until 2004,” Sister Doris said. “The archdiocese was compiling and digitizing their records of funerals and baptisms. A worker came across a death certificate saying the child was the natural child of Henriette Delille. After doing more research, they found another certificate, indicating a second child had been born to her. She probably did have these two children, both of whom died before the age of 3.”

Henriette Delille had not yet been confirmed at that time, so the revelation that she may have had two children out of wedlock did not interfere with the cause for her canonization, Sister Doris said.

A belief and hope in God

When she was 24, Henriette Delille underwent a dramatic religious conversion that she later expressed in a brief declaration of faith and love, one of the few pieces of writing that the community has from her life.

On a prayer book about the Eucharist, Henriette Delille wrote on the flyleaf page her profession of faith in French: “Je crois en Dieu. J’espère en Dieu. J’aime. Je v[eux] vivre et mourir pour Dieu.” (“I believe in God. I hope in God. I love. I want to live and die for God.”)

“It’s the prayer we always promote,” Sister Goudeaux said. “We don’t have many writings of hers, but this one, it’s very special.”

One of the few other writings the sisters have of their foundress are the rules and regulations she drew up for the The Sisters of the Congregation of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary, which was described as an organization “of [lay] pious women founded for the purpose of nursing the sick, caring for the poor and instructing the ignorant.”

In the years leading up to founding the Sisters of the Holy Family, Henriette Delille and her companions carried out many apostolic works in the city. They served as witnesses for many marriages and as sponsor for the baptisms of slave and free adults and children.

Henriette Delille lived in community with two lifelong friends, Juliette Gaudin and Josephine Charles. They went on to form the Sisters of the Holy Family, but they still encountered discrimination in the Church and society.

“They were discriminated against by other religious people, other sisters and other congregations. They couldn’t go to any church they wanted to go to,” said Sister Doris, who added that there were many in the Church at the time who doubted that women of color could be celibate.

According to an early journal, the community was very poor, and the sisters made many sacrifices to accomplish their mission.

“People brought them food and old clothes for them to wear, and shoes they could put on when it rained,” Sister Doris said. “They had to beg, and whatever they had, they shared with the poor.”

In the last 20 years of her life, Venerable Henriette Delille overcame numerous obstacles in the forms of social, political and financial opposition in carrying out her religious community’s three-pronged mandate to care for the sick, help the poor and instruct the ignorant.

When she died at age 50, her obituary said that “Miss Henriette Delille had for long years consecrated herself totally to God without reservation to the instruction of the ignorant and principally to the slave.”

More than 175 years later, the Sisters of the Holy Family continue their foundress’ legacy by doing the same corporal and spiritual works of mercy. Seeing her raised to the altars one day would be a poignant moment for many sisters who themselves experienced racism in discerning religious life.

“I’ve been in the community over 60 years. At the time I wanted to become a sister, the Sisters of the Holy Family was the only congregation in Louisiana that I could enter as a woman of color,” Sister Sylvia said.

“It would mean a lot to people of our own race that the Church is affirming that it’s possible for people of color, knowing what we went through in trying to become legitimate in the Church, that one of us could be elevated to sainthood,” Sister Thibodeaux said. “I think it would be inspiring to our people and to all people.”

Brian Fraga is a contributing editor for Our Sunday Visitor.

| Notable black U.S. Catholics |

|---|

|

Servant of God Mary Lange

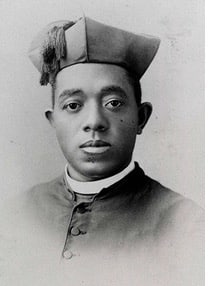

Little is known about the early life of Mother Mary Lange. Born in Cuba with possible Hatian background, Lange emigrated shortly after the War of 1812. She arrived in Baltimore where she ran a school for African-American children in her home. At the request of Sulpician Father James Joubert, Lange and another woman started the Oblate Sisters of Providence to staff a school that taught Black Catholic girls, most of whom could not read or write. Under the leadership of Mother Lange, the order’s mission grew from simply running schools to offering career development classes for women and to operating homes for widows and orphans. She died in Baltimore on Feb. 3, 1882. Venerable Augustus Tolton

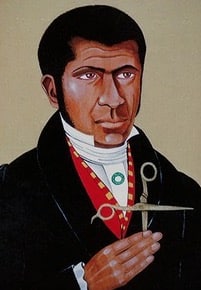

The son of slaves, Father Augustus Tolton was the first African-American ordained a priest from the United States. His family escaped into Northern territory, settling at Quincy, Illinois, where the Church pastor took the young Augustus under his wing and allowed him to enter the parish school against the wishes of many in the parish. However, when he pursued his desire to become a priest, Tolton went to Rome as the American seminaries would not accept him. Returning to the U.S. after his ordination, Father Tolton was met with racial prejudice by laity and clergy alike — with the bishop’s delegate telling him he was not to allow white people to attend his parish. Father Tolton eventually was assigned to a parish in Chicago with a growing Black Catholic community, which formed into St. Monica Church. He poured out his life in service to his people — in care for the poor and in a church building project, among other things. This strenuous work undoubtedly was a contributing factor to his untimely death at the age of 43 in 1897. Venerable Pierre Toussaint

Pierre Toussaint was born into slavery in modern-day Haiti and received his freedom in 1807. He emigrated to New York City and used his income as a hairdresser to purchase his sister’s freedom as well as that of his future wife, Juliette. The couple offered their lives to God in the care of the poor and needy. Together they adopted Pierre’s niece and fostered several orphans in their home over the years. The Toussaints also offered much assistance to help their wards learn trades, in addition to operating a credit bureau and providing a shelter for immigrant priests. Pierre boldly crossed barricades to nurse the sick and destitute during a cholera outbreak. He attended daily Mass for more than 60 years until he died in 1853. |