Early one spring evening in 1979, Father Stanley Rother left the Oklahoma mission of St. James the Apostle in Santiago Atitlán, Guatemala, to make a sick call — something he did almost every night after dinner. Mission volunteer Frankie Williams accompanied him.

They walked at a brisk but calm pace, taking deliberate, cautious steps on the dirt path, with only the light of the moon to guide them. When they arrived at the tiny, thatched hut, Williams silently followed the pastor’s lead, as he lowered his 5-foot, 10-inch frame to enter the lodging.

It was clear that the man they came to see was dying. Tomás was known as “the bishop” among his fellow Tz’utujil Mayans because of his ritual of following the priest as he processed out of Mass. He lay on a low pallet covered with reeds, surrounded by family and friends.

As soon as they saw Padre Apla’s — their name for Father Stanley in their native Tz’utujil — a human path opened up, allowing their pastor to make his way to Tomás.

Williams watched as Father Stanley sat on a tiny chair, made the Sign of the Cross and reached out to anoint Tomás. Suddenly, the dying man sat up with a shot of energy and said something in Tz’utujil, remaining there until Father Stanley finished anointing him.

Then Tomás looked at his pastor, put his hands on Father Stanley’s head and started to pray, partly singing a blessing over him in Tz’utujil. When he was done, Tomás fell back on the cot and closed his eyes.

“At that point Stan looked at me, and I could see his eyes watering,” remembered Williams, who went out with tears in her eyes and waited for Father Stanley, who handed her his handkerchief, and they began walking home. That night in Tomás’ hut, she recalled years later, “was one of the most profound experiences of my life.”

As he did with Williams, when friends, family or other volunteers came to visit, Father Stanley invited them to join him on his home visits to parishioners, wanting the visitors to experience the Tz’utujil people whom he loved and served for the last 13 years of his life.

Stanley Rother was shot in the head in the mission rectory on July 28, 1981, by three intruders who were never caught.

On Dec. 2, 2016, Pope Francis officially recognized Father Stanley Rother’s martyrdom for the Faith and for his people at Santiago Atitlán, making him the first American martyr and the first priest from the United States to be beatified — a historic event that took place Sept. 23, 2017 in Oklahoma City’s convention center.

Ordinary heroic virtue

In a world that idolizes MVPs, lauds superheroes and glorifies celebrities, to be described as ordinary could be taken as an insult. Yet one of the most inspiring things about Father Stanley Rother — the farmer from Okarche, Oklahoma — is precisely how average and ordinary he was.

Indeed, like Blessed Capuchin Father Solanus Casey and the Curé d’Ars, St. John Vianney, Father Stanley Rother’s struggles with academics almost prevented his ordination. “His beatification is a verification that God can do great things with relatively ‘insignificant’ people,” explained Bishop Daniel Mueggenborg, auxiliary bishop for the Archdiocese of Seattle. “God chose a humble virgin in Nazareth (an out-of-the-way, no-place village) to be the mother of his son. In the same way, God chose a priest from a remote rural part of Oklahoma who couldn’t learn Latin and barely passed seminary to be the protomartyr for the United States!”

| Canonization cause timeline |

|---|

|

July 28, 1981: Father Stanley Rother is killed in his rectory in Santiago Atitlán, Guatemala.

Feb. 6, 1996: Father Rother’s name is given to Pope John Paul II (on his second visit to Guatemala) as one of 78 people killed in Guatemala’s guerrilla war and believed to be martyrs for the Faith.

– 2007: Diocese of Sololá-Chimaltenango, Guatemala, approves moving the cause of Father Rother from its diocese to the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City, and the Vatican approves. The U.S. bishops vote to support opening a cause of canonization for Father Rother in Oklahoma.

– Oct. 5, 2007: Canonization tribunal is sworn in, and the archdiocesan phase of the cause of canonization of Father Stanley Rother begins.

– July 20, 2010: The archdiocesan phase of the cause comes to a close. A box of documents arrives at the office of the Congregation for the Causes of Saints in the Vatican.

– May 2012: Congregation for the Causes of Saints affirms the “juridic validity” of the case of Father Rother.

– June 27, 2012: Congregation for the Causes of Saints names an official relator for the cause of Father Stanley Rother. The relator, together with the collaborator from outside the congregation, will prepare the position paper (positio) on martyrdom.

– Sept. 3, 2014: Servant of God Father Stanley Rother’s positio is presented to Congregation for the Causes of Saints by Archbishop Paul S. Coakley of Oklahoma City and Andrea Ambrosi, postular of Father Rother’s cause.

– June 14, 2015: Vatican commission approves martyrdom in the cause of Father Rother

– Dec. 2, 2016: Pope Francis recognizes the martyrdom of Father Stanley Rother of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City, making him the first martyr born in the United States — clearing the way for his beatification.

– Sept. 23, 2017: Father Rother is beatified in Oklahoma City.

|

Although he was not gifted in any exceptional way, noted Bishop Mueggenborg, “Father Rother chose to say ‘yes’ to Jesus with his whole being. And because of that, Jesus accepted the gift of his life and united him with himself in a perfect sacrifice to the Father.”

Father Rother’s life is a reminder that heroic holiness is accessible to each one of us, “if we want it. It’s that simple … and it’s that challenging,” reflected Bishop Mueggenborg. “His life makes me ask the questions: Do I want to be holy? Do I want to follow wherever the Lord will lead me? Am I willing to give God my all so as to become all he desires me to be?”

Saints are local. They come from ordinary places like Okarche and Santiago Atitlán, yet their holy witness strengthens the Church universal.

Saints also are ordinary people, like Father Rother, who remind us that we are all called to holiness. We need that faith witness. We draw strength from those who, like Stanley Rother, live faithfully and wholeheartedly their very ordinary lives. They challenge us to believe that we can, too. This is a message of good news that we all need to hear.

A life of discipleship

Stanley Francis Rother was raised in a staunchly Catholic, German farming family, in the farmhouse where he was born on March 27, 1935. He attended Holy Trinity School for 12 years, and in between seminary semesters, Stanley returned to help with the harvest.

His sister, Sister Marita Rother, ASC, described the closeness of the Okarche community: “You could walk across a field and be at a relative’s house!”

Life for the Rother family centered on the family, the farm and on the Church and its traditions. From an early age, Stanley and his four siblings (a sister died in infancy) learned the importance of prayer and of praying together as a family.

After supper every night, they knelt by their chairs around the kitchen table to pray the Rosary. Daily and seasonal religious practices “were integrated into our daily life,” said Sister Marita. “We prayed a lot together as a family, and I know that’s what drew us closer.”

It is in this ordinary life that Stanley first experienced a personal encounter with the Good Shepherd, where he learned what it meant to live as a disciple of Jesus. This is where he learned to be a man of prayer, a hands-on servant with a resolute desire to become a priest.

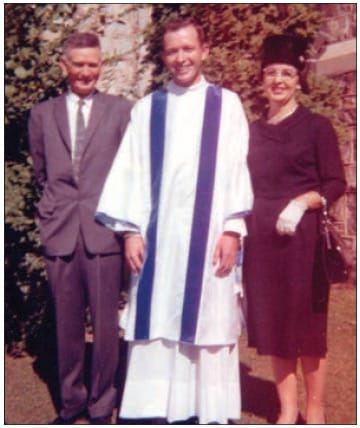

When 23-year-old Stanley flunked the first year of theology at a San Antonio seminary, he was sent home. Learning Latin proved to be a huge obstacle. Yet, when asked by his bishop, Stanley reiterated with confidence his unwavering desire to follow the call to the priesthood, and his supportive bishop agreed to find him a new seminary. In September 1959, Stanley began his studies at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary in Emmitsburg, Maryland.

Stanley persevered, becoming a priest for the then-Oklahoma City and Tulsa Diocese on May 23, 1963, at age 28. Five years later, he volunteered for Oklahoma’s mission in Guatemala, ultimately finding his heart’s vocation as a priest to the Tz’utujil Mayan people. It is here, in this ordinary life as a mission parish priest, where he experienced and integrated into his ministry the love and compassion that led him to lay down his life for the Gospel and for his sheep.

|

“His life makes me ask the questions, do I want to be holy? Do I want to follow wherever the Lord will lead me? Am I willing to give God my all so as to become all he desires me to be?”

— Bishop Daniel Mueggenborg, auxiliary bishop for the Archdiocese of Seattle

|

In fact, in a manner both humorous and courageous, that same young man who flunked seminary because he couldn’t master Latin, not only became competent in Spanish, but by the grace of God, was also able to master the challenging Tz’utujil language of his Mayan parishioners.

When she pictures her big brother in her mind today, Sister Marita said she loves seeing him standing on the porch, looking out over the village of Santiago Atitlán and smoking his pipe. But her favorite image is of him “walking down the aisle out of church, because he’s touching every person as he comes out … and the kids are running to him, and he’s patting him or her on the head. … That was his home. Those were his people.”

For most of us, ordinary life will never involve the hardships associated with extreme poverty or living in the midst of civil war and death threats. But the invitation and call to say “yes” to God with confidence that he is present in our everyday life is, in reality, the same.

Imitating Christ’s servant leadership

In his 2005 Encyclical Letter, Deus Caritas Est (“God is Love”), Pope Benedict XVI said, “Being a Christian is not the result of an ethical choice or a lofty idea, but the encounter with an event, a person, which gives life a new horizon and a decisive direction” (No. 1).

In Pope Francis’ words in Evangelii Gaudium (“The Joy of the Gospel”): “Thanks solely to this encounter — or renewed encounter — with God’s love, which blossoms into an enriching friendship, we are liberated from our narrowness and self-absorption. We become fully human when we become more than human, when we let God bring us beyond ourselves in order to attain the fullest truth of our being. Here we find the source and inspiration of all our efforts at evangelization. For if we have received the love which restores meaning to our lives, how can we fail to share that love with others?” (No. 8).

It is no coincidence that the same values Stanley learned growing up in an Oklahoma farming community — family-first, hard work, kindness, generosity, perseverance — are precisely the values that enabled him to become a missionary shepherd to the Tz’utujil when he first arrived in 1968.

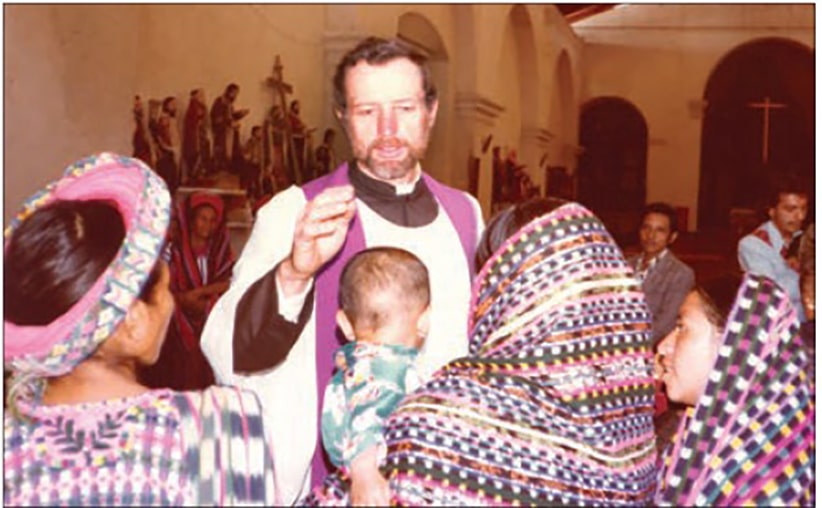

In one sense, much of the daily life for the Oklahoma missionary consisted of the same day-to-day actions of any other parish priest. Visiting the sick. Celebrating daily Mass. Training and teaching catechists. Visiting children at the parish school. Working on his Sunday homily. As well as hearing confessions, witnessing weddings, fretting over the budget and attending council meetings.

And yet, his experience was anything but run-of-the-mill. At the young age of 40, Stanley Rother became the sole priest and pastor at the Oklahoma mission, which served 25,000 Tz’utujil Mayan parishioners. He instituted a personal tradition of Sunday meals with his parishioners in their homes, where he ate whatever they ate — a practice that also led him to have regular bouts of dysentery because of the inadequate hygiene used in preparing their food.

When it came to celebrating the sacraments, the numbers alone were staggering. In 1974, for example, Father Stanley celebrated 649 baptisms, 85 weddings and 150 first Communions. Two thousand people received Communion every week.

By 1980, el conflicto armado interno — Guatemala’s violent war — had made its way to Santiago Atitlán and the other villages surrounding Lake Atitlán. In addition to his pastoral work, Father Stanley’s priestly and sacramental duties now included heartbreaking tasks such as walking the roads searching for the bodies of the desaparecidos (parishioners who had gone missing).

“The country here is in rebellion, and the government is taking it out on the Church,” Father Stanley wrote to his archbishop in a letter dated Sept. 22, 1980. “The low wages that are paid, the very few who are excessively rich, the bad distribution of land — these are some of the reasons for wide-spread discontent. The Church seems to be the only force that is trying to do something (about) the situation, and therefore the govt. is after us. … The reality is that we are in danger. But we don’t know when or what form the government will use to further repress the Church.”

“And what do we do about all this?” wrote Father Stanley to his friend, Frankie Williams. “What can we do, but do our work, keep our heads down, preach the Gospel of love and nonviolence.”

So the generous, loving pastor himself became the presence and the oil that nourished and healed them. He fed the hungry. He sheltered the needy. He called on the Tz’utujil in hiding. He visited the persecuted in prison. He clothed and took care of the widows and fatherless children. And Father Rother, servant leader for his suffering community, was hope for his people.

“We just need the help of God to do our work well and to be able to take it if the time comes that we are asked to suffer for him,” he wrote candidly to his sister. Yet even during that indescribable final year, he noted, “We aren’t actually sitting on our hands” with regard to sacramental preparation.

In 1981, with the help of Carmelite sisters and lay catechists, Father Rother received 149 for confirmation on Pentecost Sunday. And during the parish’s patron feast of St. James the Apostle in July — mere days before his death — a record high 101 couples had their marriages witnessed by Father Stanley, and more than 200 Tz’utujil received first Communion.

Author Henri Nouwen wrote about his experience visiting Santiago Atitlán three years after Father Rother’s death. “Stan was killed because he was faithful to his people in their long and painful struggle for human dignity,” dying not for an abstract cause or an issue, but for his people, in whom he recognized the face of the suffering Lord. His martyrdom needs to be told, for “martyrs are blood witnesses of God’s inexhaustible love for his people.” Ultimately, Nouwen wrote, we honor martyrs because they are signs of hope for the living Church; they are reminders of God’s loving presence.

Although our version of servant leadership may never demand that we lay down our life, our opportunity to serve in the here-and-now we live is just as real.

A ‘Marian style’ missionary disciple

“There is a Marian ‘style’ to the Church’s work of evangelization,” wrote Pope Francis in Evangelii Gaudium. “Whenever we look to Mary, we come to believe once again the revolutionary nature of love and tenderness. In her we see that humility and tenderness are not virtues of the weak but of the strong who need not treat others poorly in order to feel important themselves” (No. 288).

Mary is able to recognize the traces of God’s spirit in events great and small, Pope Francis wrote. “She constantly contemplates the mystery of God in our world, in human history and in our daily lives. She is the woman of prayer and work in Nazareth, and she is also Our Lady of Help, who sets out from her town ‘with haste’ (Lk 1:39) to be of service to others” (No. 288).

Rooted in the Rother family’s prayerful devotion to Our Lady, Stanley had a special relationship with Mary. As a seminary student, Stanley often implored Our Lady’s maternal intercession by offering the Rosary for friends and family members with special needs.

Father Thomas Connery, a classmate from the Diocese of Albany, New York, remembered how “Stan had a great love and devotion for the Virgin Mary,” and Our Lady’s Grotto at Mount St. Mary’s was a special place of prayer for him. In his second year at the Mount, Stanley was named assistant grotto chairman, becoming grotto chairman the following year.

|

“[Father Rother] has inspired me since I first learned about his life and death while a seminarian at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary — Father Rother’s alma mater. The impact of his heroic witness and martyrdom has been an inspiration and a challenge to me ever since.”

— Archbishop Paul S. Coakley of Oklahoma City

|

Father Connery recalled Stanley’s “gentle spirit and easy way about him. He was a big, strong, generous man. He was easy to meet and easy to get along with — an open spirit.” Stanley influenced their small, close-knit seminary class with his “discipline and prayerful spirituality.”

Father Stanley celebrated every Mass “as though it was very personal, the most important Mass of his life,” noted Frankie Williams, who was Methodist. In the same slow, thoughtful way that he spoke, Father Stanley celebrated the Eucharist, “with deliberate reverence and attention.” Williams remembered being with Father Stanley as he celebrated Mass for two people and for 3,000 people — “always with feeling and adoration and celebration. He never once hurried through one.” With him, “everything was done in a very gentle, quiet manner.”

Throughout his life and through his priestly service, Stanley Rother lived what St. Francis of Assisi commended to the members of his community: “Let all the brothers preach by their deeds.” With humility and love, he became one with his Tz’utujil parishioners to show them — not just tell them — how much God loved them. He was, as the Year of Mercy challenged us to be, “merciful like the Father” — and always confident in seeking his heavenly Mother’s intercession.

Patron of missionary discipleship

In Evangelii Gaudium, Pope Francis described what he calls “evangelizing gestures.” Often little and always powerful, these are the acts and attitudes that mark a Christian as a missionary disciple.

Much like Elijah, who recognized God’s presence on the mountain, not in awesome phenomena but in something apparently insignificant — a whisper — Father Stanley Rother “preached” fully this incarnational spirituality in his everyday life, understanding the importance of presence in living these “evangelizing gestures.”

By constantly striving to be present to the people in front of him, to the needs in front of him, he proclaimed a God who lives and suffers with his people. In the end, the choice to die for his Tz’utujil was a natural extension of the daily choice he made to live for them — and in communion with them. His death was nothing less than a proclamation of God’s love for the poor of Santiago Atitlán — a truth still remembered there 36 years after his martyrdom.

Even before Pope Francis began to challenge every Catholic to go to the peripheries, to live as missionary disciples, Father Rother had discovered his place and his mission in a remote part of Guatemala, noted Oklahoma City Archbishop Paul S. Coakley. “He had moved well beyond his comfort zone to embrace a life of missionary discipleship far from the familiar comforts of Oklahoma.”

| Learn more about Stanley Rother |

|---|

|

Find out more about the priest who ministered to the people of Guatemala through the book “The Shepherd Who Didn’t Run” (OSV, $19.95) by María Ruiz Scaperlanda. For more information and to purchase the book, go to osvcatholicbookstore.com

|

Father Rother’s heroic love and witness, added Archbishop Coakley, “has inspired me since I first learned about his life and death while a seminarian at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary — Father Rother’s alma mater. The impact of his heroic witness and martyrdom has been an inspiration and a challenge to me ever since.”

Salvador Atzip Sosof remembered during his wedding how Father Stanley told all the couples being married about St. James and the apostle’s martyrdom, “then we went to confession one by one. Afterwards he gave us a remembrance, a diploma [marriage certificate] and a medal,” which Father Stanley blessed. He told Salvador that the medal was to remind him of his Mother Mary.

And when there was nothing that he could say with words to comfort his suffering parishioners, Padre Apla simply gave them his presence.

As Father Stanley wrote to his archbishop, “Given the situation, I am not ready to leave here just yet. But if it is my destiny that I should give my life here, then so be it. I don’t want to desert these people, and that is what will be said. … There is still a lot of good that can be done under the circumstances. … Pray for us that we may continue to serve as best we can in the reality where we find ourselves.”

Our missionary journey to the peripheries of our life will inevitably be different than the one encountered by Blessed Stanley Rother. But the question we face is the same. What brave thing has God put in front of me to face right now? Whether it’s with my marriage, or my children, or my health or my need to forgive — will I say “yes” in trust that it will lead me to eternal life? He can show us how.

As the martyr from Okarche concluded in his final Christmas letter from the mission in 1980, “The shepherd cannot run at the first sign of danger. Pray for us that we may be a sign of the love of Christ for our people, that our presence among them will fortify them to endure these sufferings in preparation for the coming of the Kingdom.”

María Ruiz Scaperlanda writes from Oklahoma.