What is a miracle? By the very etymology of the word — mirari (to be amazed) — it seems to be a rare, inexplicable blessing that is an occasion of God’s benevolent interference in our lives. These special moments go beyond the upending of our expectations or mere marvels, and they are common to all of us — at least the seeking of them.

We all pray for “miracles” of one sort or another. Perhaps a sports fan prays for an impossible Hail Mary pass at the end of a football game or a student begs God to pass a test that he expects to fail. Someone who despairs of finding a lost wallet might desperately beseech St. Anthony for some help. We hope for that dream job or pray to be lifted from a financial difficulty by some sort of divine intervention.

In times of the serious illness of loved ones, we approach God in great faith with our desperate plea that their lives might be spared. Sometimes the little coincidences of daily life seem to be miraculous reassurances that we are always under the care, protection and watchful eye of a loving Father.

As Catholics, our own miracle stories, big and small, are all woven into the vast tapestry of a faith tradition that embraces supernatural events and celebrates them in ways that we may not even realize. For any of us that wear a Miraculous Medal or scapular in any of its various colors, we are indirectly recalling the time-honored apparitions of the Virgin Mary in which these sacramentals find their origins. Even the most famous of all sacramentals, the rosary, comes from a foundational miracle story that St. Dominic received it in a vision in the year 1208.

Our entire faith rests on the reality of two great supernatural events: the Incarnation and the Resurrection. All around the world Catholics are experiencing a miracle every hour of every day at Mass when bread and wine are truly transformed into the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ. Even skeptics who dismiss supernatural events outright like famed atheist David Hume who argued that “miracles are impossible because miracles can’t happen” still need to have an explanation for the inexplicable.

Defining the miraculous

The Catholic Church employs a strict standard when evaluating and validating miracles as authentic supernatural events worthy of the belief of the faithful.

In the recent film “Miracles from Heaven,” a mother, played by Jennifer Garner, prays for the healing of her young daughter, Annabelle, who suffers from a rare life-threatening gastro-intestinal disease. In the most dramatic scene of the film, the girl, playing in an old tree with her sister, falls from a great height and hits her head, resulting in a concussion. She is rushed to the hospital and, after testing, doctors declare her to be in perfect health — not only did the fall not harm her, but her previous health issues have miraculously disappeared.

This incredible miracle story has left audiences inspired and amazed, but it is interesting to note that the example of this cure would not pass the strict medical criteria of the Catholic Church. When it comes to validating healing miracles that are used in the canonizations of saints or those that pass the scrutiny of the Lourdes Medical Commission at the famed site of the 1858 apparitions to St. Bernadette Soubirous, the criteria used to determine them to be medically inexplicable are extremely strict.

For the cure to be considered miraculous, the disease must be serious and impossible (or at least very difficult) to cure by human means and not be in a stage at which it is liable to disappear shortly by itself. No medical treatment must have been given, or it must be certain that the treatment given has no reference to the cure. The healing must be spontaneous, complete and permanent — all conditions which apply to Anabelle’s incredible recovery. But the final criteria is not met — because it was produced by another crisis (or disease) it would make it possible that the cure was wholly or partially natural.

Because of these nearly impossible standards, the Lourdes Medical Commission, while documenting over 8,000 extraordinary cures, has only validated 69 of them. When the Vatican investigates a miracle worked through the intercession of a would-be saint as part of the evaluation of whether this person has lived a life of heroic virtue and is with God, interceding for us, the same set of rules is employed.

Medical miracles by themselves are difficult to validate with so many strict guidelines, but in canonization causes an additional difficulty lies in that the prayers to a potential saint must be only directed exclusively to that singular person (not to other saints in addition). It almost seems to be a miracle that they find any miracles suitable for use in canonizations. The medical commission for the Congregation for the Causes of Saints features over 60 doctors in various specialties and, locally the investigation is spearheaded by an uninvolved doctor appointed by the bishop.

The history of miracles

The Church has always been enriched by the fruits of miracles. The prodigies produced by Christ established his divinity and attracted disciples to him. The apostles were emboldened with a mandate to work miracles in establishing the Church. The Roman emperor Constantine first was inspired to legalize Christianity in the year 312 after witnessing a vision in the sky of the IHS Christogram.

Throughout the ages, religious orders like the Servites and Mercedarians have sprung out of the mystical experiences of their founders. In addition to marking thaumaturgical (wonderworking) saints on feasts throughout the year, we celebrate the supernatural throughout the Roman calendar with commemorations for Divine Mercy, Our Lady of Lourdes, Our Lady of Mt. Carmel, Our Lady of Fatima and Our Lady of Guadalupe. Some of the most breathtaking churches of the world have a supernatural foundation with four of the largest 12 places of worship (by square footage) in Christendom tracing their origins to an apparition of the Virgin Mary. Countless numbers of people per year go on pilgrimage to sites of miracles all over the world including the millions of sick who seek healing at the waters of Lourdes and the believers who come times on their knees to venerate the prodigious image of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City. Additionally, millions of conversions are owed to this vision on Tepeyac hill, as well as to the Miraculous Medal and other devotions that have stemmed from miraculous beginnings.

For all the excitement that miracles can bring, Pope Francis has encouraged us to not think of God as “a magician, with a magic wand.” Miracles can be a source of inspiration for an enlivened relationship with Christ, but it is important to not engage in a distracted pursuit of the latest claim of supernatural phenomena or a modern day Gnosticism, seeking secret knowledge at the expense of an authentic practice of faith grounded in Christ. The Church seeks to safeguard the faithful by performing serious investigations into credible miraculous claims and providing judgments and recommendations on how we should approach these specific instances of the seemingly miraculous.

For the skeptics that might suggest that the Church has something to gain by promoting every dubious alleged event in order to attract people back to the pews or inspire people to spend money buying religious paraphernalia at a new shrine, the reality is that the entire unspoken goal of these investigations is to shut down the distraction and prove that nothing miraculous is in fact occurring to return people to a more grounded practice of the Faith. Likewise, the investigations are so rigorous that very few claims have even the potential of being considered to be supernatural events. Most interestingly, even in cases of thoroughly investigated and approved miracles like the famed apparitions at Lourdes and Fatima, the Church does not require Catholics to believe in these events or incorporate the devotions into their lives of faith.

Types of miracles

Different miracle types require different types of attention in investigations by the Church. Perhaps the clearest cases are those where science carries the most weight in evaluating the authenticity of the event. In Eucharistic miracle reports, where the host is said to have physically turned into bleeding flesh, the wafer is typically confiscated by authorities at the instruction of the local bishop to perform scientific tests that can easily ferret out a hoax from an authentic miracle. In some extremely rare cases, actual human blood or heart muscle has been found to be present with the host, including a 1996 example in Argentina positively verified by then-Archbishop Jorge Mario Bergoglio, the future Pope Francis.

Investigations of weeping icons employ science to uncover trickery or natural explanations like leaky duct work in a church building. In one case from 1953 documented on film, Pope Pius XII on Vatican Radio declared the statue of the Weeping Madonna of Syracuse, Italy, to be an authentic miracle of lachrymation. The statue, given to a young couple as a wedding gift, passed scientific scrutiny and wrought hundreds of verified miracles, including the restoration of the sight of the woman who owned the statue. Other statues like the one of Our Lady of Akita in 1973 in Japan have been verified by scientists to produce human blood.

Alleged cases of the stigmata — that is, those people mystically exhibiting the wounds of Christ in their hands, feet and forehead — rely heavily on thorough medical examinations to rule out fraud. The most famous modern stigmatic, St. Padre Pio, a Capuchin monk from Pietrelcina, Italy, with many purported mystical gifts, underwent medical tests and scrutiny in silence while the Church verified these extraordinary events. The number, location and size of the wounds of stigmatics vary widely, suggesting that stigmata is a phenomena where the recipient at least in part experiences the Passion of Christ according to their personal understanding of it. There have been no known cases of stigmata successfully reproduced by hypnosis.

More complex are those cases that involve reports of visions and messages of Jesus, the Virgin Mary or the saints. While authentic Eucharistic miracles and bleeding statues are incredible signs undoubtedly with great unspoken meaning for the faithful, the alleged instances of a person receiving divine communication require a special level of thorough and swift attention by Church authorities in order that people are not lead astray. Science has attempted with mixed results to evaluate with brain scans and other testing to reveal and understand the brain activity of the visionary. In the end, however, the Church must establish whether the witness is reliable and trustworthy. Throughout the ages, over 2,500 Marian apparitions have been reported but only a tiny fraction have been validated.

Church investigation

Throughout history church authorities have validated hundreds of reports of miraculous events. But miracles were not always subjected to a strict investigative process. Most occurrences that have any level of ecclesiastical sanction are from the early centuries of the Church and only enjoy a traditional mode of approval. That is, their recognition as supernatural events typically was rooted in a strong sensus fidelium, or universal acknowledgment from the faithful.

Eventually, however, miracles with divine messages perhaps intended for the universal Church required that more developed guidelines be drawn up. The revelations of St. Birgitta of Sweden were considered at the Councils of Constance (1414-1418) and Basle (1431-1449) and the Fifth Lateran Council (1512-1517), called by Pope Julius, reserved the approval of new prophecies and revelations to the Holy See. The Council of Trent (1545-1563) sought to return investigations to the local level and authorized bishops to approve such phenomenon after rigorously investigating with science to accompany the prayerful discernment that had marked inquiries of the past.

Further rules regarding miracles were developed by Prospero Lambertini (1675-1758), the future Benedict XIV, who provided guidance for the evaluation of private revelations and the miracles needed with the canonization of saints in De Servorum Dei Beatificatione et de Beatorum Canonizatione in 1840. He argued that reason must be used to determine whether such events are truly extraordinary and beyond the scope of natural causes.

This work included De Cadaverum Incorruptione, in which he addressed incorruptible bodies of some saints, insisting that their miraculously non-decaying needs to be close to perfect preservation over the course of many years. A rare case of incorruption used for establishing sainthood is St. Andrew Bobola, whose corpse endured rough handling during several relocations and still remained perfectly fresh for more than 300 years. Throughout history, the bodies of over 350 saints have been identified as being in a state of extraordinary preservation for some time.

Communicating judgment

The most recent Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) document and the current standard that lays out the guidelines for the judgment of apparition claims is the Normae Congregationis de Modo Procedendi in Diudicandis Praesumptis Apparitionibus ac Revelationibus (“Norms of the Congregation for Proceeding in Judging Alleged Apparitions and Revelations”), approved by Pope Paul VI on February 27, 1978, and written sub secreto in Latin for the eyes of bishops alone but made public in 2012.

According to this document and canon law, the competent authority is the local bishop, who may make a public judgment on the authenticity of a miracle claim with no follow-up Vatican commentary necessary. Although the diocesan bishop possesses the right to initiate an investigation, that country’s national conference of bishops can subsequently intervene at his request or at the request of a qualified group of faithful. If necessary, the Vatican can then also intervene if the situation involves the Church at large or if discernment requires it.

The classic modern example of the progression in the levels of intervening authority is the controversial Medjugorje alleged apparition case, in which the famed long-running phenomena involving six children in Bosnia-Hercegovina that began in 1981 was first investigated and discouraged by the local ordinary, was later examined by the 1991 Zadar Commission of the Yugoslavian bishops, and then was reevaluated by a Vatican commission formed in 2010 whose results are currently unknown.

Typically, if the situation merits it, the bishop will seek a report from an assembled commission of experts such as theologians, psychologists, psychiatrists, Mariologists or anthropologists. They assess the phenomena and the people who report them, looking for evidence of authenticity. Next they are to study any messages that are associated with the extraordinary reports, to ascertain whether they conform to Church teaching. The third question raised by the document appraises the pastoral implications of the phenomena by studying the impact of the reported apparitions. Miraculous physical healings, conversions, vocations and a return to the sacraments are considered to be good fruits.

There are three categories of apparition judgments that relate most importantly to the supernatural character of the event. The negative category that asserts that the event is not worthy of belief is given by the Latin formulation constat de non supernaturalitate, that is, “It is established that there is nothing supernatural.” The negative criteria include errors in the facts of the case or in doctrinal attributions to Jesus or Mary, the pursuit of financial gain and psychological disorders in the visionary. A lack of humility and obedience to Church guidance can be common red flags as well.

A second category of judgment, non constat, “not established as supernatural,” is the one of uncertainty, calling for a “wait and see” stance. The vast majority of investigated apparitions receive this assessment when the investigative committee cannot at that time make a definitive conclusion. An apparition with such a designation might or might not be of supernatural origin. While there is no proof of the phenomenon originating from anything but natural causes, none of the negative criteria are fulfilled and the supernatural cause is not ruled out.

In extremely rare cases, an event is established as supernatural, constat de supernaturalitate. There must be moral certainty or at least great probability of the miracle occurring, the visionary and the content of the revelations must be evaluated positively and there must be healthy devotion with good spiritual fruits. When an apparition is approved, the Blessed Virgin Mary can be venerated in a special way at the site but it often takes decades or longer for a local bishop to issue a definitive statement.

In one extreme case, the 1664 visions reported by Benedicta Rencurel in Le Laus, France, were finally validated in 2008. In the only such example in the United States, Bishop David L. Ricken of Green Bay initiated an investigation where a team of three renowned Mariologists examined the merits of the 1859 claims of Adele Brise, a Belgian farm worker who reported that she saw the Blessed Virgin Mary on three occasions and began to spread her messages of conversion and catechesis. After the commission concluded, Ricken declared in 2010 that there was enough evidence to declare with confidence that these supernatural events were “worthy of belief” and contained nothing contrary to the teachings of the Church.

While not required for an apparition or other miracle to be considered approved, occasionally the Vatican will provide another layer of recognition by releasing an official document, constructing or elevating a basilica, canonizing a visionary, establishing a feast day or simply having the pope visit that location with a special Marian prayer or with a symbolic golden rose. Only 28 times since the Council of Trent has a local bishop declared an apparition to be “worthy of belief,” and of those only 16 have received additional recognition from the Vatican.

Miracles of all types have played a major role in the growth and sustaining of the Catholic Church throughout the ages. The Church embraces the authentic occurrences of God working in our world after rigorously examining and rendering judgment on these major supernatural occurrences in an effort to protect us. But not every blessing merits a full investigation by a Vatican commission.

Sometimes it is the small miracles that grace our lives that serve as gentle reminders that God is indeed there watching out for us.

Michael O’Neill is the author of the new book “Exploring the Miraculous” (OSV, $19.95) and a contributor to the cover story of the National Geographic December 2015 issue “Mary: The Most Powerful Woman in the World.” He hosts the weekly radio program “The Miracle Hunter™” on Relevant Radio.

| Miracle Glossary |

|---|

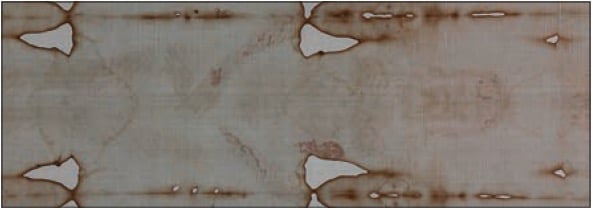

Acheiropoeita Acheiropoeita (“not made with human hands”) are a particular kind of icon which are said to have come into existence miraculously. The image of Our Lady of Guadalupe (1531) and the Shroud of Turin (never authenticated by the Vatican) are famous examples.

Apparition

A corporeal vision of Jesus, the Virgin Mary or the saints to one or more witnesses typically at the same location over time. The most famous apparitions are those of Mary under such titles as Our Lady of Fatima (1917), Our Lady of Lourdes (1858) and Our Lady of Guadalupe (1531).

Eucharistic Miracle

Eucharistic miracles are extraordinary phenomena relating to a consecrated host. Examples include the host turning visibly into human flesh, bleeding or surviving hundreds of years without decomposition. The most famous Eucharistic miracle occurred in Lanciano, Italy, in the eighth century.

Glossolalia

Glossolalia is the spiritual gift usually referred to as “speaking in tongues.” The term can either mean the ability to communicate in a natural language not previously studied or in the utterance of meaningless syllables said to be the “language of angels.”

Incorruptibles

Generally seen as a sign that a deceased individual is a saint, incorruptible bodies have avoided the normal process of decomposition. Some bodies remain in perfect condition, while others discolor over time. A famous example is the incorruptible body of St. Bernadette Soubirous (1844-1879), the visionary from Lourdes.

Inedia Literally meaning “not eating,” inedia is the mystical phenomena of surviving on no food or on the Eucharist alone for sustenance. St. Catherine of Siena (1347 -1380) exhibited this ability.

Lachrymation

The term lachrymation refers to the phenomena of a weeping statue or icon that exudes human blood, tears or fragrant oil. The Weeping Madonna of Syracuse (1953) was famously declared authentic by Pope Pius XII on Vatican Radio.

Levitation

Levitation is the mystical rising of a human body into the air. St. Joseph of Cupertino (1603-1663) was a Franciscan friar known for his frequent levitations.

Locution

Unlike apparitions, locutions are not bodily appearances perceived with the eyes of a visionary but rather audible messages or interior understandings experienced by the recipient. Famous but unapproved modern examples of locutions are those alleged by Father Stefano Gobbi (1930-2011) and the messages associated with the Our Lady of Akita phenomena (1973). Pareidolia

Pareidolia is a false perception of imagery due to what is theorized as the human mind’s over-sensitivity to perceiving patterns. A famous example would be the Virgin Mary cheese sandwhich.

Stigmata

Considered to be a visible sign of sanctity, the stigmata is the mystical appearance of the wounds of Christ spontaneously on the recipient’s body. A stigmatic may manifest one or all of the marks of the crucifixion. Tradition holds that that first stigmatic was St. Francis of Assisi (1181-1226) while the most famous modern example is St. Pio of Pietrelcina (1887-1968).

|