Pick an age. Any age. Pick a culture. Any culture. Pick a time, pick a place,and then pick a person. Whoever they are, wherever they are, and whenever they are, the same questions haunt them: Who am I? Why do I exist? What will make me happy? Do I matter?

Those are the eternal questions. And their answers have eternal ramifications. They determine how we live and what we love. They shape the choices we make, the work we do and the time we spend. They give life, and they take life.

That is why it’s imperative that we find the right answers. And there are right answers. Not just good answers, but the answers, true answers, answers that always and everywhere give peace, happiness and life.

And where can those answers can be found?

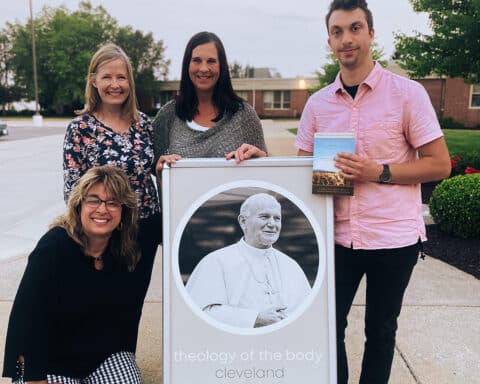

In Pope John Paul II’s theology of the body.

The theology of the body is more than a book or a collection of teachings from papal audiences. It’s the Catholic vision of what it means to be a human person, made in the image and likeness of God. It conveys the ancient truths of the faith in a new, accessible and relatable way, explaining for postmodern man the relationship between the body and the soul, man and woman, and the human person and God.

It is, in fact, the Catholic sacramental worldview, understood, structured and articulated for a culture plagued by a diseased understanding of the cosmos.

Ultimately what it shows us is our vocation: our path to love, holiness and joy.

Emily Stimpson is an OSV contributing editor. She attended the first gathering of the National Theology of the Body Congress near Philadelphia last month.

VOCATIONAL BASICS

For all Christians, the theology of the body tells us, our primary vocation is the same: to become self-gift.

Becoming self-gift means that God has entrusted to each and every one of us the task of giving ourselves in love to him and to one another. We are, in fact, to become increasingly like God, who, in his very essence, is self-gift: Three Persons giving themselves eternally in love to each other.

To become self-gift is our primary vocation.

But that primary vocation is lived out through a specific vocation.

Traditionally, the Church has recognized three such vocations: marriage, religious life (which includes consecrated singlehood) and the priesthood. Until recently, unconsecrated singlehood has not been considered a vocation, but rather a state in life. That’s because it’s typically only a stage passed through on the way to choosing a permanent vocation.

The growing number of Christians remaining permanently in the single state — some by choice, others for reasons beyond their control — has sparked a debate about whether or not unconsecrated singlehood can be considered a vocation. That debate has yet to be resolved.

Regardless of how that question is settled, the answer doesn’t change the ultimate vocation to which we’re called. All of us must learn how to give, not take, and love, not lust, according to the inner demands of the life to which we’ve consented, if not chosen.

And that’s where the theology of the body comes in. It not only tells us what our primary vocation is, but it also shows us the eternal meaning of each earthly vocation and gives us guidance for living it well.

At its most basic, it does that by unpacking one verse from Sacred Scripture: Genesis 1:27. “God created man in his image; in the divine image he created him; male and female he created them.”

That verse tells us three things.

First, both man and woman together image God. Both are like him. To know a man and to know a woman is to know something of God.

Second, we image him not just in our souls, but also in our bodies. Something about our bodies conveys a supernatural truth. It speaks. It has a language. It expresses the nature of the person.

Third, there is difference from the very beginning. There is man, and there is woman, and we are made for each other. Like corresponding puzzle pieces, we fit. And when we come together, new life results.

On those truths, the theology of the body’s teachings on vocations rest.

MARRIAGE

Marriage, the theology of the body tells us, is a sacrament, a perpetual sign of three fundamental realities.

First, it reminds us that we are made for communion with others. We are made to be in relationship.

We know that, said Janet Smith, who holds the Father Michael J. McGiveny Chair in Life Ethics at Sacred Heart Major Seminary in Detroit, because of our bodies, which possess a meaning that is spousal: God designed them to be given in love to another. And because we are our bodies, that means God designed us to be given in love to another. It is not good for man to be alone.

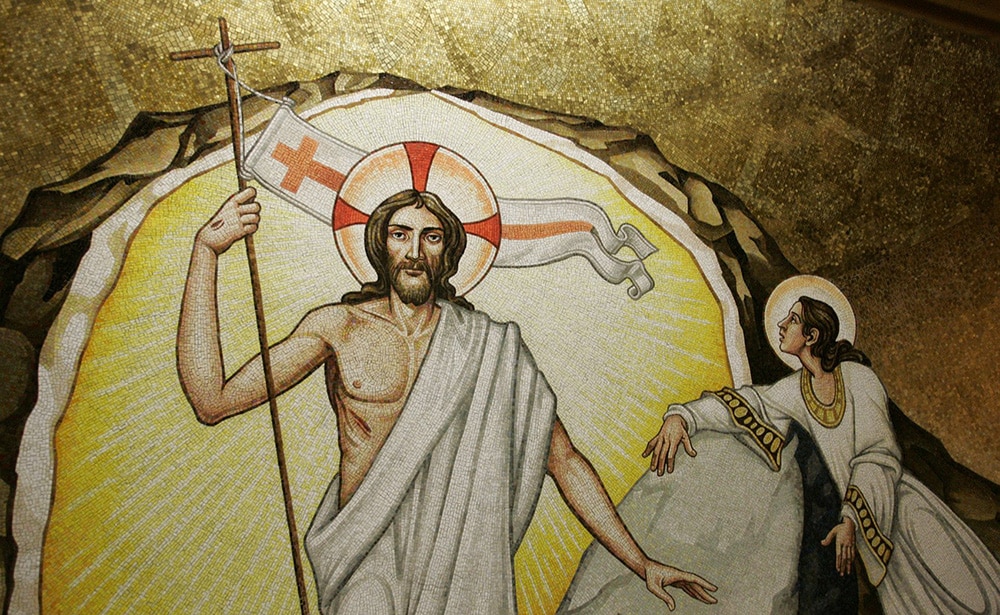

Second, marriage reflects the relationship between Christ and his Church. This, said Smith, is the “great sign” of Ephesians 5. Christ is the Bridegroom. The Church is the bride. He seeks her out, strives to make her holy, and for her, lays down his life.

Finally, because the body says something of God, so, too, does the union of two bodies. When two become one, we learn that the inner life of the Trinity is self-giving, life-giving love. In Smith’s words, “God is a lover.”

Those fundamental realities are more than food for thought for theologians. According to the theology of the body, they also give married couples a model on which to base their own marriage.

Knowing they are called to become self-gift, married couples need to approach each day with the goal of sacrificing their own needs and desires in order to serve their spouse.

“That doesn’t mean being a doormat,” Smith said. “It means making all your decisions with the other person in mind. It means recognizing that your life is bound up with their life, that they can make claims on you that no one else can.”

It also means, she added, “waking up each morning and asking yourself what you can do this day to please your spouse.”

Likewise, it tells us that marriage is meant to be an exclusive love relationship, where the goal is helping your spouse become holy and where the marital act is always marked by openness to life. Just as Christ and his Bride, and the Father and the Son hold nothing back in their love, neither can couples hold anything of themselves back, including their fertility, when they come together in the marital act, which is the sacred sacrament of their union.

As a practical guide for how to live those teachings, the theology of the body points couples to the biblical Song of Songs.

According to Michael Waldstein, translator of the definitive edition of the “Man and Woman He Created Them: A Theology of the Body” (Pauline, $29.95), the mystics have long recognized the Song of Songs as an allegory for the relationship between Christ and the Church, as well as between God and the soul. That’s why, while writing the theology of the body, Pope John Paul II plumbed the poem’s depths, meditating on what the truths revealed by it mean for married love.

The fruit of those meditations, said Waldstein, tell couples that just as the bridegroom in the Song calls his beloved, “My sister, my bride,” so must every husband strive to see his wife as a sister. That requires not treating her as an object of lust, as a thing to be used, but rather, Waldstein explained, “with disinterested tenderness,” recognizing “in her femininity, the many beautiful facets to her being.”

Likewise, the husband must see his wife “as a garden closed.” He must recognize, Waldstein explained, that she “is the master of her own feminine mystery.” Both can and should delight in each other’s bodies, but that delight, marked by “awe and wonder,” has to be tempered with respect.

“The man can’t simply walk into the garden and eat the fruit,” Waldstein said. “He has to recognize the mastery she has over her own mystery and wait for it as a gift.”

Finally, in the Song of Songs, the bridegroom and the bride continually seek each other. So, too, then in human marriage, noted Waldstein, must husband and wife continually strive to know and love the other more purely and deeply. Nothing can be taken for granted. Nothing can be assumed. Love must be sought and nourished so it can grow.

RELIGIOUS LIFE

Marriage signifies the spousal nature of humanity: We are meant for communion. But ultimately, the theology of the body tells us, we are meant for communion with only one Spouse.

“Christ calls all of us to be his bride,” said Janet Smith. “Our ultimate relationship with God himself is meant to be spousal.”

It also, in a sense, is meant to be virginal.

“Virginity means to be totally God’s, body and soul,” explained Sister Helena Burns of the Daughters of St. Paul, who leads workshops for teens on the theology of the body. “In heaven we will all be married, but we also will all be virgins.”

The vocation of religious life speaks to both those destinies. On earth, the religious give themselves body and soul to God, as virgins and brides. Christ is their spouse in the here and now, not just in eternity, and they live their life for him. No one else can claim them or call them their own.

That, explained Sister Helena, is why religious life is not a sacrament.

“We are already living the reality,” she said.

According to Sister Helena, the theology of the body helps religious understand both the spousal and virginal nature of their vocation. It reminds them that they, like all men and women, are called to communion. They are to make a gift of themselves to their “community, family, friends and the people we serve.” It also reminds them, that just as husbands and wives give themselves exclusively, body and soul, to one another, they must make the same gift to Christ.

“It’s not just about being freed up to serve,” she said of the religious’ life of celibacy. “It’s about being in an exclusive love relationship with Jesus.”

That understanding of religious life, articulated by the theology of the body, also helps religious understand that they’re not denying their body through a perpetual vow of chastity. They’re not pretending they don’t have one. Rather they’re giving it to God.

That gift, explained Sister Helena, is akin to the “yes” a woman gives her husband. Although the woman, when she marries, in effect says “no” to sexual intimacy with every other man, she’s not thinking about the “no.” She’s thinking about the “yes” and all that entails.

That “yes” to God is also a “yes” to spiritual parenthood. The theology of the body teaches that the body’s orientation to motherhood and fatherhood, an orientation that enables it to create and nurture life, isn’t denied any more than the body’s spousal nature is denied by religious life. Rather, it is lived on the spiritual level.

And that isn’t a lesser motherhood or a consolation prize for those who don’t have biological children.

Rather, said Father Thomas Loya, a national speaker on the theology of the body, spiritual parenthood “is real motherhood and fatherhood,” because, “ultimately, what gives us life is life in the Spirit.”

PRIESTHOOD

Just as the theology of the body calls religious men and women to live their vocation spousally, so does it call priests to live their vocation spousally. But unlike religious, who live that spousal relationship primarily with Christ, the priest lives it primarily with the Church.

“The priest isn’t just the shepherd who lays down his life for his sheep,” said Father Roger Landry, a priest of the Diocese of Fall River, Mass. “He’s the husband who lays down his life for his bride and makes her holy.”

Seen through the prism of the theology of the body, the priesthood is all about serving the Bride: providing for her through the sacraments and protecting her from sin. For her sake, the priest denies himself marriage and em-braces continence, giving himself as exclusively to the souls entrusted to him as a husband does to his wife.

In that, the priesthood not only reminds us of Christ’s love for his Bride, but, in a way similar to vowed religious, also reminds us of the ultimate spousal meaning of the body.

“To be a happy celibate, you have to live it spousally,” said Father Thomas Loya. “The celibate draws inspiration and encouragement from married people. They remind him that he has to live his celibacy in a spousal dimension. Otherwise it’s meaningless, just a bunch of restrictions. In the same way, the celibate reminds the married person of the eschatological dimension of their marriage.

“The one thing we can never escape and which is embodied in the priesthood,” he continued, “is that ultimately we are made for, belong to, and will return to God.”

That exclusivity between the soul and God demands continence of the priest (even married Eastern-rite priests must abstain from marital relations the day before celebrating the Divine Liturgy), as well as a deep prayer life.

“The theology of the body tells us that in prayer, we discover who we are and who we’re called to be,” said Father Landry.

When priests neglect the spousal understanding of their vocation and their virginal relationship to God in prayer, it becomes nearly impossible to remain faithful to their calling.

“The priest must see his life as one of spousal love,” said Father Landry. “Without it, he gets lost. The recent scandals show us this.”

Finally, the theology of the body helps the priest live his vocation to care for his bride. It gives him the language he needs to speak to the souls in his care.

“For the priest,” Father Landry said, “the theology of the body takes away the shame of speaking out about the truth of the human person and human sexuality, as if the Church’s teachings were bad news instead of good news. … It gives us the model and the method for how to confront the modern experience and modern life.”

SINGLE LIFE

Unconsecrated singlehood may or may not be a vocation, but for all those who find themselves in this state in life, whether permanently or only temporarily, the theology of the body still provides unparalleled guidance.

That guidance starts with the reminder that single people, like married couples, religious and priests, are also called to be self-gift.

“We are all created for communion with God and with the other people around us,” said Anastasia Northrup, president of the Theology of the Body International Alliance. “We can only find ourselves through the gift of ourselves.”

That reality, she continued, places a special responsibility on single people to discern why they’re still single. They have to look past the cultural counterfeits — careers, commitment-free relationships and the pursuit of their own selfish desires and comforts — and see what God really wants from them. They have to seek healing from the wounds inflicted by past relationships, sexual sin and a culture of divorce. They also must fight the cultural temptation “to keep all options open,” thinking that, “there’s always something better waiting around the corner.”

As they move through the discernment process, single people need to heed the theology of the body’s call to ongoing conversion, making a gift of their life each day to God and trusting God even in the darkest times, when no easy answers to their single state present themselves and when the absence of a spouse leaves them struggling with loneliness and unfulfilled desires.

“We must consent to what we did not choose,” said Northrup, noting that the acceptance of unwanted singlehood is one of the most important ways single people can die to themselves and make a gift of their life to God.

Finally, with their eye on their final end — their virginal, spousal union with Christ in heaven — single people need to seek out opportunities to live selflessly.

Through small acts of kindness to strangers, service to friends, and apostolate work among those in need, single people can live the theology of the body by putting their bodies, as well as their souls, in love’s service.

“The married person puts their spouse first,” said Janet Smith. “The celibate puts God first. When you’re single, the next person who crosses your path is the person you put first. That’s who Christ is asking you to give yourself to. That’s how you love him.”

Theology of the Body Basics

Pope John Paul II’s theology of the body…

…Was first given during the course of 133 Wednesday audiences delivered from 1979 to 1984.

…Is an anthropology of what it means to be a human person, a union of body and spirit.

…Teaches that the body expresses the person and reveals how men and women are made in the image and likeness of God.

…Reveals that the one flesh union of husband and wife points to the life-giving communion within the Trinity.

…Shows how using another person for our own pleasure violates the dignity of the human person.

…Illustrates how the celibate life is a sign of the total self-gift we are all called to make of ourselves to God.

…Calls all human beings to make a gift of themselves to one another in love.

Congress unpacks pope’s theology

How can Catholics take the teachings of the theology of the body and not only apply them to everyday life but teach the culture how to apply them as well?

That question was at the heart of the first National Theology of the Body Congress. Held just outside of Philadelphia July 28-30, 2010, the congress brought together more than 25 internationally recognized experts on the theology of the body to unpack what many believe to be Pope John Paul II’s greatest theological legacy.

In talks ranging from an exegesis of Ephesians 5 to a meditation on the theology of the body and the priesthood, theologians, philosophers and popular speakers such as Janet Smith, Michael Waldstein and Helen Alvare helped illuminate the meaning of Pope John Paul II’s catechesis on the human person for vocations, social policy and the Christian life.

The conference, which was put on by the Theology of the Body Institute and sponsored, in part, by Ascension Press and the Our Sunday Visitor Institute, attracted more than 450 attendees. Those attendees hailed from 10 different countries and 39 U.S. states. Two bishops, 50-plus priests, six deacons, dozens of religious, and Catholics from 111 different dioceses were present.

One of those attendees was Christopher Chapman, associate director for Youth and Young Adult Ministry in the Diocese of Pittsburgh.

“What was reinforced for me at this Conference was that TOB is a sacramental appraisal of the universe, with creation and the Incarnation at the heart of every TOB meditation,” said Chapman. “In that sense, it is important to realize that TOB is not just some branch of theology, but the fundamental way of seeing the world as a Catholic.”

That vision is exactly what Philadelphia Cardinal Justin Rigali called participants to share in the months and years ahead.

At the conference’s final Mass, the cardinal called the theology of the body “the curriculum of the culture of life,” and urged participants to teach that curriculum through their lives and work.

“This congress must not end,” he said. “The contribution of the speakers and participants, the fruits of the seminars, discussions and artistic performances must advance still further. This congress must become a campaign of human and catechetical formation.”

How to spread theology of the body within dioceses

1. Meet with your bishop to discuss your hope that a concerted effort be made to introduce the theology of the body to your diocese.

2. Start a theology of the body study group with your friends.

3. Encourage your diocese to use a marriage preparation program that includes the concepts of the theology of the body.

4. Encourage your parish to introduce the theology of the body to its youth group and feature the theology of the body in its adult education program.

5. Ask your diocese to declare a Year of the Theology of the Body.

6. Plan a theology of the body conference in your area.

7. Have your diocesan director of continuing education schedule theology of the body speakers for the priests of the diocese.

8. Contact your seminary rectors to introduce theology of the body to the seminary curriculum.

9. Launch a theology of the body website with free resources.

10. Start a column on theology of the body in your diocesan paper.

Adapted from a handout compiled by Matthew Pinto, president of Ascension Press, for the symposium Man and Woman He Created Them.

Resources

Here are just a few groups you can contact for study guide materials, parish resources and speakers.

Theology of the Body International Alliance: Speakers, study guides, parish resources and more; www.theologyofthebody.net.

Theology of the Body Institute: Parish resources, conferences, speakers and more; www.TOBInstitute.org, 215-302-8200.

Imago Dei, Inc.: Conferences, study guides and more; www.imagodei-tob.org, 202-962-0040.

Ascension Press: Marriage Prep, Adult Education and Youth Ministry materials; www.ascensionpress.com, 610-696-7795.

Tabor Life Institute: Theology of the Body for Teens; www.TaborLife.org, 708-645-0762.

Women of the Third Millennium: Retreats, talks and books; www.wttm.org, 480-720-5715.