It seems strange — but accurate — to say the saints were a greedy bunch when it came to grace. They just wanted more, more, more — and pretty much would stop at nothing to get it.

Sacrifice? Sure! Poverty? No problem! Imprisonment? You bet! Martyrdom? Bring it! All for grace here and now on earth. And forever in heaven.

But — first things first — in a nutshell, what is grace? Here are two points the Catechism of the Catholic Church makes when defining and explaining it:

- “Grace is favor, the free and undeserved help that God gives us to respond to his call to become children of God, adoptive sons, partakers of the divine nature and of eternal life” (CCC, No. 1996).

- “Grace is a participation in the life of God. It introduces us into the intimacy of Trinitarian life: by Baptism the Christian participates in the grace of Christ, the Head of his Body. As an ‘adopted son’ he can henceforth call God ‘Father,’ in union with the only Son. He receives the life of the Spirit who breathes charity into him and who forms the Church” (CCC, No. 1997).

Simply put, it’s a really good deal, but where exactly does greed fit into this? While pride may place first on the list of the seven deadly (or capital) sins, avarice — or greed — is a close runner-up.

Again to the Catechism:

- “Sin creates a proclivity to sin; it engenders vice by repetition of the same acts. This results in perverse inclinations which cloud conscience and corrupt the concrete judgment of good and evil. Thus sin tends to reproduce itself and reinforce itself, but it cannot destroy the moral sense at its root” (CCC, No. 1865).

- “Vices can be classified according to the virtues they oppose, or also be linked to the capital sins which Christian experience has distinguished, following St. John Cassian and St. Gregory the Great. They are called ‘capital’ because they engender other sins, other vices. They are pride, avarice, envy, wrath, lust, gluttony, and sloth or acedia” (CCC 1866).

So, the saints were sinning to get something good? Of course not. Pedal to the metal, they flew through life doing good and always wanting to do more of it. Receiving God’s grace in countless ways and always wanting to receive more of it.

And — here comes the “bad” news — doing just that offers proof that we can do the same. They started life just as we did and faced all of its hardships and temptations. (Not to mention all of the difficult or challenging people who can populate our path on the road to heaven.)

Each and every one of those “greedy” saints sinned, repented and moved forward. No doubt we have a lot of experience with the first of those three, but it’s the second and third that are the tricky ones. And that’s where, for lack of a better term (here adapting a line from a 1987 movie) “good greed is good.”

Good greed works … for the good. For you and, through you, for others. A few points to consider:

1. Grace is for others, not you

Caritas (“charity”) is the opposing virtue of avaritia (“greed”). Wow! Nothing like tossing in a little Latin to make something sound impressive. But, in this case, the idea is impressive. One we’d be wise to impress on our minds. The sin of greed is me, me, me, while charity is you, you, you, and us, us, us. But, of course, “greedy for grace” isn’t a sin, because it has nothing to do with selfishness. It’s all about selflessness. It’s all about better doing God’s particular will for you and wanting, and working toward, more grace.

2. Grace is a treasure

A couple of Jesus’ parables are about being greedy, about taking all your money and all your time and spending it on what you really, really want.

“‘The kingdom of heaven is like treasure hidden in a field, which a man found and covered up, then in his joy he goes and sells all that he has and buys that field. Again, the kingdom of heaven is like a merchant in search of fine pearls, who, on finding one pearl of great value, went and sold all that he had and bought it'” (Mt 13:44-46).

Grace, “a participation in the life of God,” is the treasure. It’s the pearl. It’s what the saints found and what — through their lives of sacrifice — became more and more theirs. Or, rather, more and more, they became God’s.

3. The more grace, the better

This good kind of greedy gets easier, or maybe better put, gets less difficult, because with grace comes “the life of the Spirit who breathes charity into” you. Sins builds on sin (“creates a proclivity to sin”) and grace builds on grace. Let’s use the metaphor of a couch potato, something many of us can identify with when we look in the mirror.

The longer we just sit, the harder it is to get up and do something. On the other hand, over time, short walks can lead to longer walks. And, if we’re young enough and our knees can take it, those short walks can lead to short runs and then, even longer runs. The good news is that grace doesn’t depend on our knees. (Yes, feel free to kneel in prayer, but praying while sitting, walking, driving or even lying down is just fine, too.) Throughout our day — throughout your day — God gives us opportunities to grab fistfuls of grace by acts of charity, selflessness and sacrifice. Chances to be nothing short of greedy.

Bill Dodds writes from Washington.

| A tale of ‘greed’ and grace |

|---|

|

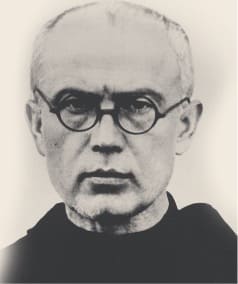

Young Raymond was a handful. Or, as one biographer put it, “a lively boy, quick-witted and just a trifle headstrong.” A good but not perfect kid who readily accepted appropriate consequences from his parents when he went a little too far. His pranks might not have tried the patience of a saint, but they did get on the last nerve of an exasperated mother who one day shouted, “I don’t know what will become of you!” Her words deeply touched him. The 12-year-old changed, spending more time alone in front of their home’s small shrine to the Blessed Mother. Now, he was more prone to tears. Somehow he would slip into his own little world. Alarmed (and, who’s to say, maybe feeling a little guilty for her strong words), his mother asked him what was going on. At first he refused to answer, but when she pressed he told her what, later, he would make public: “That night I asked the Mother of God what was to become of me. Then she came to me holding two crowns, one white, the other red. She asked me if I was willing to accept either of these crowns. The white one meant that I should persevere in purity, and the red that I should become a martyr. I said that I would accept them both.” Bless his sweet, innocent, greedy little heart.  A short time later he entered a local Franciscan seminary, prospered and — one year before his ordination in Rome in 1918 — founded the Militia of Mary Immaculate, an apostolate that promoted Marian devotions. His own love for and relationship with Our Lady continued to deepen. Returning to his native Poland in 1927, he began the “Cities of the Immaculate Conception,” an institution that gained great popularity in Poland, Japan and India. In 1941, he was arrested by the Gestapo and sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp. That same year he was executed after volunteering to take the place of a fellow prisoner — a husband and father — who had been among those selected to be killed in retaliation for a prisoner escaping. Canonized by Pope John Paul II in 1982, little Raymond — Father Maximilian Kolbe — had lived a life of purity and died a martyr. Everything he had asked for and ever wanted. |